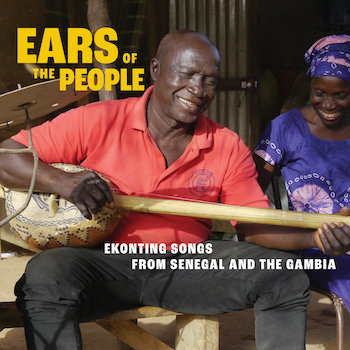

Folk Album Review: “Ears of the People” — Ekonting Songs from Senegal and the Gambia

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

The banjo’s African relative makes its American debut via a new Smithsonian Folkways album.

The recent resurgence of interest in both the African origins of the banjo and the history of Black string music can be largely attributed to one person. In the ’70s Laemou-Ahuma (Daniel) Jatta came from the Gambia to study at Friendship College, an HBCU in Rock Hill, South Carolina. When he first heard someone playing the banjo, he found the sound beautiful and familiar. He was told that it was an instrument made by African slaves. He also learned that it had once been made of a gourd and was played in an overhand/down-picking style. That information confirmed his hunch: the banjo bore an undeniable resemblance to an instrument his father played, the ekonting (akonting).

The recent resurgence of interest in both the African origins of the banjo and the history of Black string music can be largely attributed to one person. In the ’70s Laemou-Ahuma (Daniel) Jatta came from the Gambia to study at Friendship College, an HBCU in Rock Hill, South Carolina. When he first heard someone playing the banjo, he found the sound beautiful and familiar. He was told that it was an instrument made by African slaves. He also learned that it had once been made of a gourd and was played in an overhand/down-picking style. That information confirmed his hunch: the banjo bore an undeniable resemblance to an instrument his father played, the ekonting (akonting).

Jatta and his father belonged to the Jola (Diola), a people spread through the Casamance region of Senegal as well as parts of the Gambia and Guinea Bissau. The ekonting accompanies many events and ceremonies in Jola daily life, just as the banjo had, for generations, been a routine part of plantation life in anglophone North America. The Jola, also responsible for introducing rice cultivation to the Americas (the Carolina lowlands in particular), perform on the instrument to relax together after work, another similarity with early banjo culture. Also notable: the Jola play the ekonting to celebrate local wrestling heroes, another common interest shared with plantations across the Atlantic. Other connections between the banjo and the ekonting include the “clawhammer” downstroke playing style (o’teck in Jola), short “thumb” drone string, full-spike neck, M-shaped bridge, and animal-hide head. Despite all this, for a long time the accepted wisdom about the banjo’s origins ignored the ekonting.

Jatta continued his education in accounting and economics, a trajectory that would bring him to Stockholm, where in 1999 he gave a presentation on the ekonting that was attended by Swedish historian and banjo-enthusiast Ulf Jägfors. Jägfors had long been dissatisfied with the conventional explanation: that the banjo descended from the wooden plucked lutes of West African griots (bards and oral historians), like the xalam, ngoni, and hoddu. Jatta’s presentation confirmed his suspicions. Other instruments may have contributed to the evolution of the banjo, but the ekonting was the closest thing to a living relative — an archetype that was being ignored.

Not only is the organological construction of the ekonting closer to that of the earliest banjos than other instruments, but the o’teck technique is the only down-picking style used in West Africa today. Beyond that, the cultural resonance of the ekonting more closely resembles that of the banjo. Unlike the music of the griots, for example, neither is typically played for the prestige of patrons; they are for the enjoyment of the community. One could argue that the ekonting was an instrument meant for the ears of the people. Jatta and Jägfors went on to present their findings at the 3rd Annual Banjo Collectors Gathering in Boston in 2000. Since then, the banjo and roots music in general have experienced a renaissance in America. In Africa, as well, ekonting has seen a revival, and Jatta has gone on to found the Akonting Center for Senegambian Folk Music.

Given the considerable recent interest in the instrument, it is surprising that no album of ekonting music had been released until this month. Smithsonian Folkways’ collection, Ears of the People: Ekonting Songs from Senegal and Gambia, is now here to fill the gap. It was recorded in the Jola village of Mlomp in Senegal by Scott V. Linford in collaboration with Jatta, and features nine artists over 25 tracks. The first is “Watu Eriring bee Kaolo” (“The Time Has Come to Rest”) by Musa Diatta. The title suggests that the song is meant to tell the community to take a break from work. This and Diatta’s other contributions, “Celestine” and “Aliinom (Ballanta),” are solo performances, reminding us that both ekonting and banjo are traditionally played without accompaniment. One would be mistaken to interpret the lone voice and strings in Jean “Kangaben” Djibalen’s “Elenbeja” as plaintive. In fact, Djibalen is rather, like Fred McDowell in “Shake ‘Em on Down,” rallying women to loosen their derrières. The album includes other such examples of how the ekonting can be both a solo and dance instrument, simultaneously.

The style of elder Abdoulaye Diallo, who contributes three tracks, may reach even farther into the past when he sings about political as well as amorous entanglements. Meanwhile, locally renowned band Sijam Bukan — led by Jules “Ekona” Diatta — celebrates a wrestler in “Mamba Sambou.” Ekona’s ekonting and vocals are accompanied by a driving rhythm created by spoons on a pot lid, dancers with bamboo clappers, and drums beating a rhythm associated with Jola wrestling. Sijam Bukan returns with “Diego” (about a local soccer game), “Asum Bunuk” (which celebrates the person who brings the palm wine), and the eponymous “Sijam Bukan.” Esukolaal, a group featuring Elisa Diedhiou (who also offers some individual performances), also shows a more modern interest in musical accompaniment.

Adama Sambou and Ejam Kasa present an ode to the mythical sisters who became the progenitors of the Jola and the Serer people who live to the north in “Aguene Diambone.” There are references here to the long-term conflict over Casamance secession in Senegal; in this way, this story reaches back to older traditions that bound these two peoples. Researchers such as Mark Davidheiser and Ferdinand de Jong have written about how conflict resolution in Senegambia relies (uniquely) on persuasion through appeals to common norms and interpersonal ties. These observations have led researchers to dub the region as a “joking nation” — which makes the area ripe for transatlantic historical investigations, given that both the modern banjo and standup comedy emerged from African American culture as transmitted through minstrelsy.

Master of ekonting — Ejam Kasa. Photo: Ejam Kasa

“Adiatta Ubonketom” by Elisa Diedhiou, a rare female ekonting player and songwriter, brings the earliest recordings of the American banjo to mind. When we hear this song alongside minstrel-style banjo recordings by Dave Macon or the recently rediscovered Charles A. Asbury, the link between these instruments becomes easy to grasp. Bouba Diedhiou’s “Kanyalen Rosalie” also contains technical ingredients that banjoists may recognize from 1855’s Briggs’ Banjo Instructor, particularly in songs such as “Injin Rubber Overcoat” and “Briggs’ Corn Schucking Jig.”

This album will hopefully inspire even more interest in the ekonting. But it should also kick up some curiosity about the Jola and other peoples of West Africa. Black Americans — and the Black diaspora more generally — will continue to look for ways to reconnect with the African continent. It is revealing that Jatta, an African in the US, made the connection between the banjo and the ekonting. Africans observe the US more closely than we do them. Meanwhile, Black Americans have long been subject to having their culture(s) weaponized against them. Plantation wrestling, rather than resulting in something like Afro-Brazilian capoeira, haunts us in scenes of Black men forced to fight each other for whites’ amusement, as in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (although no historians have ever found evidence of this). The banjo itself became a vehicle that could be exploited to demean Black culture.

On the other hand, when those in the US have tried to grasp their Africanness (or the Africanness of the US), drawing on their knowledge of the continent, they have inevitably fallen short. As I’ve written elsewhere, this has sometimes generated significant distortions. Even the Black Power movement of the ’60s and ’70s was limited in its knowledge to what anglophone academia thought it knew about Africa, which was then exported to other parts of the diaspora (or even, perhaps, to Africa itself). The existence of the Jola and their ekonting invites a healthy reconsideration, not only of what we know about Africa, but what we know about America. As Jatta has sung in a song written by his father, “USA c’est l’afrique” – “the USA is Africa.” It is, in the Senegambian tradition, a direct appeal to interpersonal ties.

Jeremy Ray Jewell hails from Jacksonville, FL. He has an MA in history of ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. His website is www.jeremyrayjewell.com.