Music Remembrance: Burt Bacharach — Stealth Pop Composer

By Steve Provizer

Without us even knowing it, Burt Bacharach opened up our ears.

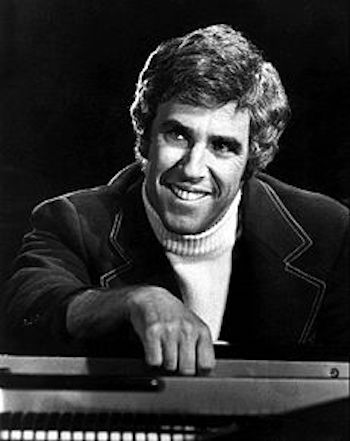

Burt Bacharach in 1972. Photo: Wiki Common

There aren’t a lot of ’60’s pop songs that I look back on with as much respect as nostalgia. Of these, most were written by Burt Bacharach, stealth pop music genius, who died on Februar 8, aged 94. Without us even knowing it, Bacharach opened up our ears.

He wrote everything from schlock to bombast; songs that were performed by everyone from Marty Robbins and Perry Como to Elvis Costello, and film songs from “The Blob” to “Raindrops (Keep Falling on My Head)” and “What’s New Pussycat.”

He had successful collaborations with lyricists Hal David and Carole Bayer Sager; otherwise, his best-known musical associate and the one with whom he had the most success was singer Dionne Warwick. In the ’60’s, before I discovered Ella, Carmen, Sarah, Billie, and company, I saw Warwick a number of times. Call Warwick near-beer, but a concert where she performed the Bacharach repertoire was, in its fashion, akin to Ella singing the songbooks of Berlin, Porter, and Gershwin.

Like those other masters of the Great American Songbook, Bacharach was a subversive. Under the cover of writing songs for the popular charts, he was able to sneak in tricky and sophisticated harmony, odd time signatures and meters, and melodies that covered a wide vocal range. Irving Berlin had his “Puttin’ on the Ritz” and George Gershwin his “Fascinating Rhythm,” but what Bacharach did was, in its context, even bolder. Berlin and Gershwin operated in a popular musical culture that was lyrically and musically sophisticated, while Bacharach’s tunes were surrounded on the charts by teenage love songs, rock and roll, and Motown.

His output is riddled with odd and shifting meters and irregular bar lines. Some of these include: “Anyone Who Had a Heart” (4/4 to 5/4, and a 7/8), “I Say a Little Prayer” (4/4/, 10/4, 11/4), “Promises, Promises” (4/4, 5/4, 7/4). Also: “Wives And Lovers,” “Do You Know the Way to San Jose,” “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again,” “Walk on By.” Take a song like “Alfie,” which, on one level, is simply lovely. Looked at more closely, the tune is packed with musical anomalies. The first A section is 10 bars, the second, eight, and the third, 14. Then, the third A repeats only the first two bars of the other A’s before it takes a whole new melodic and harmonic direction in the next five bars. The melodic line follows the lyric line almost literally, spinning out without the least concern of getting back home, until of course, it does. The chord changes are odd enough to give the best jazz musician pause.

As a kid, Bacharach had a sharp ear. He recalled how hard Ravel’s “Daphnis et Chloé Suite” hit him when he was a teenager. He also cites the influence of jazz: “I would go to the clubs on 52nd Street with my phony I.D. and just listen.… What I heard … turned my head around.” It’s also possible that Bacharach’s period of study with composer Darius Milhaud had an influence. Wherever it came from, hats off to Burt Bacharach. When listeners put his music on their turntables, they knew they’d be getting lovely, catchy, and emotionally arresting tunes. They were, but they were also getting more than what they hadn’t bargained for.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.