Folk Album Reviews: Hearing The Real Thing — Field Recorders’ Collective’s Commitment to Traditional American Music

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

The Field Recorders’ Collective is dedicated to preserving and distributing non-commercial recordings of traditional American music that are not available to the general public. In January, FRC took three gems out of the archive and made them available to stream and download.

Luther Davis and Hus Caudill from the cover of Luther Davis & Hus Caudill – FRC750

In the ’70s Tom Carter, now a retired professor of architectural history, made field recordings of traditional music and stories in the South. Some of the artists he recorded have entered the old-time music canon, like Tommy Jarrell and Fred Cockerham. In 1973-1974, Carter collaborated with folklorist Blanton Owen on a field recording project in Southwest Virginia funded by the National Endowment of the Humanities called “Traditional Instrumental Music From Southwest Virginia: A Field Collection and Oral History.” The original field tapes are at the Library of Congress, with copies in UNC’s Wilson Special Collections Library. Recordings from these tapes were included in a two-volume LP in 1976 entitled Old Originals: Old-Time Instrumental Music from Somerville’s Rounder Records. Otherwise, they have barely seen the light of day… until now.

The 1976 Rounder LPs based on Carter and Owen’s field recordings. Source: ebay.

The Field Recorders’ Collective (FRC) is dedicated to preserving and distributing non-commercial recordings of traditional American music that are not available to the general public. While other labels (Document Records, Dust-to-Digital, etc.) mainly make a business out of reissuing classic commercial recordings of early American music, the nonprofit FRC finds and preserves important field recording collections that may have never seen a widespread, commercial release. It explains on its website, “Although some recordings […] have been shared privately and informally among collectors, they have never before been made readily available to the entire old time and traditional music community.”

In January the FRC released three albums featuring music and interviews with Luther Davis and Hus Caudill from the Carter/Owens 73-74 collaboration, taking these gems out of the archive and making them available to stream and download. Both Davis and Caudill lived near Galax, Virginia, a small town with a very large reputation in American roots music. As the story goes, three Galax locals invented country music there in 1924. Brothers Al and Joe Hopkins decided to explore what career opportunities they could find in the new phonograph industry. Another local, Henry Whitter, had recorded “Wreck On the Southern Old 97” with Okeh about an incident that happened in their childhood down the road in Danville. Soon after, light opera singer Vernon Dalhart recorded another version of it, proving that local music and storytelling could both be profitable and respectable. The Hopkins brothers teamed up with barber Alonzo Elvis “Tony” Alderman inside his barbershop in downtown Galax to form a group called The Hill Billies, originating the recording industry term “hillbilly music,” the original name for what we now know as country music.

Since then, Galax has been a pilgrimage site for music history enthusiasts and has hosted an annual Old Fiddler’s Convention since 1935. Local names such as Emmett Lundy and Charlie Higgins loom large, while names like Luther Davis and Hus Caudill are not as well known, despite the fact that those musicians occupied the same time and space. That’s why what can be gleaned from their performances in the FRC’s releases is so valuable. People continue to gravitate to the small town of Galax after all these years because it is considered a primal source — it is a chance to touch a bit of the cloth from which the fiddlers of yore were cut. As generations have passed, new technologies have made this past more accessible to more listeners. The FRC continues this quest.

The abbreviated titles of the new FRC releases are Luther Davis – Old-Time Galax Fiddling, Hus Caudill – Old-Time Alleghany County Fiddling, and Luther Davis & Hus Caudill – Old-Time Galax-Style Twin Fiddling. Additional information on the releases can also be found on the FRC site (here, here, and here). Comparing the tracklists, the only songs previously released by Rounder are Davis’s “Piney Wood Girl” and Caudill’s “Waves on the Ocean” and “Traphill Tune.” Davis’ solo album features his own take on “Waves on the Ocean”, a.k.a. “Flying Indian,” which helps us differentiate their styles. Davis represents the older, more solitary fiddler tradition, while Caudill’s style is more pristine and ready for accompaniment.

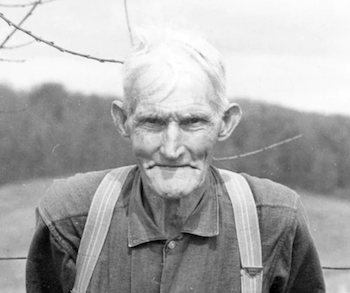

The Caudill family was from over the state line in North Carolina’s Alleghany County. Hus’s father, Sidney Caudill, was a contemporary of Emmett Lundy. It is possible that, when Sidney’s sons Joe and Hus asked that Carter and Owen seek out Luther Davis because he “knew all the old tunes,” they wanted to bring in a musician who they thought sounded a lot like their father. Carter says “Hus’s playing bridges the gap between the older, more individualistic style of his father’s generation and the newer, more formulaic, banjo-fiddle ensemble music that was gaining popularity in and around Galax during the first years of the 20th century.” Davis would probably have agreed. In 2006 Don Mussell shared some memories of visiting Davis at his home in Grayson County, Virginia, writing that “Luther said that most of the bluegrass music now being played there all sounded the same to him, that he didn’t enjoy it, and that I could learn the ‘right’ way to play from an old fellah like himself.”

Luther Davis from the cover of Luther Davis – FRC745.

There are many other observations to be made comparing just these recordings alone. They would not only reflect the past but our present as well. For example, there is Davis’s discussion of Emmett Lundy, immortalized in his 1926 recordings with Ernest V. Stoneman on Okeh records, including “Piney Woods Girl”. Lundy’s father was a preacher, and Carter and Owen wanted to know if Davis was aware of any tension between the father and son on account of the devilish fiddling. Davis responded: “Every man lives his own life. We all know how fathers can’t change their sons a lot of times. If he could mine’d changed me a many a-times!” …and the culture wars continue!

We are in danger of losing such illuminating nuances of historical memory, and not only because people die. A new wave of technology challenges us to hoist the tattered flags of our elders once again. Commercial interest in early American music exists, but its contours are primarily shaped by the recording industry, which seeks to celebrate itself and write our musical history in its own image. Supporting the FRC and its releases is a fantastic way to ensure that America’s musical legacy remains in the hands of the common folk.

Jeremy Ray Jewell hails from Jacksonville, FL. He has an MA in history of ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. His website is www.jeremyrayjewell.com.

Tagged: Field Recorders' Collective, Hus Caudill, Luther Davis, americanmusic, ballad singer, banjo, earlycountry