Theater Review: “Made in China 2.0” — The Art of Taking Risks

By Bill Marx

Made in China 2.0 is valuable as an act of theatrical witnessing, the voice of a rebel who is facing considerable challenges from the powers that be.

Made in China 2.0 written and performed by Wang Chong. Co-directed by Chong and Emma Valente. Presented by Arts Emerson at the Emerson Paramount Center’s Jackie Liebergott Black Box, 559 Washington Street, Boston, through February 12.

Wang Chong in Made in China 2.0. Photo: Mark Pritchard.

This will be a short review.

First, a snippet from a December, 2019 story in the South China Morning Post: “A rebellious spirit is very dangerous. If an artist is in trouble in China everybody will cut connections, cooperation and conversation with them,” writer-director Wang Chong said on the sidelines of the 7th annual Wuzhen Theatre Festival near Shanghai. Wang, 37, was the creator of a scene in which an actress – playing US espionage whistle-blower Edward Snowden – imitates a gun with her hand, aims it at a security camera, and fires. It is the sort of content unlikely to be approved in China’s surveillance state.” As I will make clear later, an artist with “a rebellious spirit” is dangerous everywhere, not just in China.

Arts Emerson is presenting the world premiere of Wang Chong’s Made in China 2.0, but the theater strongly suggests — though it does not require — that the press refrain from dealing with any elements in the piece that are critical of China “solely for the reason of Chong’s safety.” During his one-man, one-hour long presentation, the performer himself asks that the audience not talk about what they have seen on social media. He is afraid of how Chinese authorities might respond to evidence of the show’s ‘controversial’ material. I respect the caution, but the irony of these warnings is absurdly obvious. The issues raised in this autobiographical reflection from one of “Beijing’s most creative, provocative theater directors” must be shut down in American media because of fear — which means that intimidation wins and silence prevails. Still, safety first. Though as Wang himself dramatizes, the Chinese government could easily enlist someone to record the show. So he might well be punished anyway — without getting the word out about his social concerns as far as they might go.

I will write about what I can. Those who want details should email me. I can’t do any comparison and contrast because I have not seen Wang’s previous work, though I did hear him interviewed about what sounded like an amazing online version of Waiting for Godot. As a performer, the writer-director is personable and amusingly self-depreciating. Tall and lanky, Wang comes off as boyishly gawky at times, particularly when he details, with self-evident pride, how he went about creating some of the experimental productions he has mounted in China. (He is the founder and artistic director of the Beijing-based performance group Théâtre du Rêve Expérimental.) Wang’s unshakable earnestness is admirable though not always convincing. He never shows much anger or disgust. His rocky (?) relationship with his father (where is his mother?) is tilted toward comedy rather than pathos. The production makes modest use of technology (a video camera) and provides some striking images — particularly variations on a sheet of blank paper — though I would not rev up the fog machine so often.

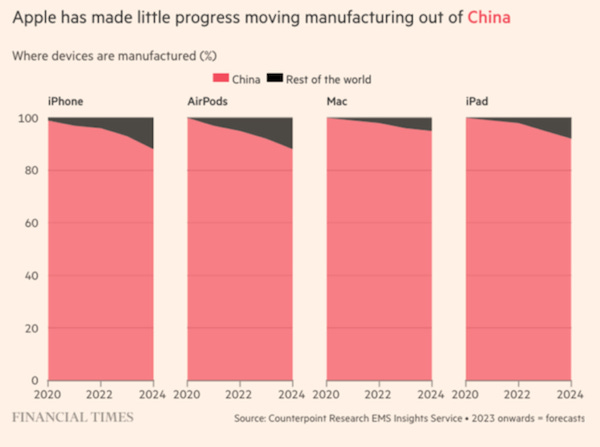

Because Made in China 2.0 focuses so closely on the man’s experiences — with a few looks back at history — the production’s reach is frustratingly limited. Theater is a collaborative art, but we hear nothing about the contribution made by the actors and designers Wang has worked with. There is a section about the country’s struggles with COVID, but the government’s treatment of the Uyghurs is ignored. And, though I can’t touch on political matters, aren’t economic concerns fair game? What about globalization? Its impact (for better and worse) on China and the West? Wang has staged several productions outside of his homeland (he is a bit of an international star), but the director says little about how global business arrangements have aided and abetted the current situation. Talk of deglobalization is trending but, as Adam Tooze points out in a recent column, the tech giant Apple is still knee-deep in the country. See the chart below:

Keep that in mind as you head out to the Apple Store.

For me, Made in China 2.0 is valuable as an act of theatrical witnessing, the voice of a rebel who is facing considerable challenges from the powers that be. And, since the Arts Emerson guidelines don’t preclude addressing American theater, let’s place Made in China 2.0 — and its courageous writer-director — up against what is produced on Boston’s stages. We are told this is a time of crisis: the climate emergency, the war in Ukraine, the fragility of our democratic institutions. Apparently, our theaters believe this is overblown hand-wringing. Where is our political theater? Where is our experimental theater? Where are the plays that threaten the status quo to the point it flinches in pain? Has anyone here produced a drama that deals with the perfidy of global surveillance programs? It sounds like Wang did. Where are the dueling utopias and dystopias? Instead, it is business as usual, with all eyes turned to Broadway. What’s at stake there is financial success or failure: will the upcoming revival of Evita at the American Repertory Theater be boffo? Made in China 2.0 is a reminder that theater — in the hands of artists who want to do more than sell product or titillate tourists — is about taking risks. As I said, “a rebellious spirit” is a very dangerous thing — everywhere.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of the Arts Fuse. For four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Arts Emerson, Chinese Theater, dissident theater, Made in China 2.0., political-theater

The flippancy of most of this review is unfortunate and disregards Wang Chong’s artistry, activism, and importance in and beyond China. The reviewer could have easily learned about Wang’s work in greater context (reviews, interviews, videos, and academic articles are all available online). The performance I attended indeed fully engaged the audience in laughter and spontaneous moments of applause–as well as extended collective moments of awed and solemn silence, and individuals breaking down in tears and audible sobs. The description in the review does not reflect the impact the performance had on others who attended–and does not even touch upon what it stirs in the hearts of viewers from China (the sold-out audience was mix of ethnicities, age groups, and genders). And the risk Wang takes at this particular moment is real–friends of audience members who were present are currently being held by authorities for far less.

What you call flippancy can be credited to the limitations of how I could review the show. Arts Emerson gave critics “suggested” parameters regarding what they could discuss — because of reasonable concerns about Wang Chong’s safety. I make that point in my review — it is hard to talk about how some audience members broke down in tears when you cannot refer to what they were reacting to. Also, criticism should not be reduced to reporting how audiences members respond to a show or performer — it is about the independent evaluation of the critic. This event posed a challenge — no one wants to endanger a voice of dissent. So it seemed best to err on the side of caution.

As for Wang Chong’s past pieces, the point of theater is to see it live. I wrote about what I saw in front of me. I did view an online interview with Wang Chong about his “Waiting for Godot” and that sounded fabulous. I would have loved to have seen that. But I was not writing a feature article on Wang Chong, but a review of this particular show. The fact is, there strengths as well weaknesses that are often part and parcel of any one-person, autobiographical drama.

Where we do agree is in our deep admiration for Wang Chong and the risk he is taking, as well as for members of his audience here and elsewhere. That is why I ended the review the way I did — we need more theater artists of courage. If only more theater companies in America were as valiant as Wang Chong — not just by presenting his work (as valuable as that is), but mounting productions that, like his, challenge the status quo. For example, dramatizing the ways big American businesses, including Apple (as I mention in the piece) enable the current situation. Wang Chong looks at China — we need American theater artists to scrutinize our country with the same fearlessness.

I would agree with you, if I didn’t grow up in China. As an American you won’t understand the amount of courage it takes for him to be standing there. I know you are disappointed that instead of hatred, you only see how much the Chinese director care about his country. Before you want to hear more on the Uyghurs or economics, read Lu Xun will help you understand the play better, if you want to.

You don’t specify what you agree with in the review, so I can’t respond to that point. There is nothing in my piece or comments to suggest in any way that I am disappointed that the director cares about his country. For me, criticizing your homeland about where it falls short is a sign of love. I wish more American theater artists had Wang’s courage — which I admire greatly.

As for the Uyghurs, besides the critic Lu Xun I would suggest readers turn to We Uyghurs Have No Say: An Imprisoned Writer Speaks by Ilham Tohti. This magazine reviewed that book, which I read and would highly recommend. The preface by Rian Thum lucidly sets out the history of the Uyghurs, their current plight, and the rise of Chinese Islamophobia. Tohti’s reasoned critique of “ethnonationalism” has much to say of interest outside of the borders of China. Also, I reviewed a fascinating novel, The Backstreets, by the Uyghur writer Perhat Tursun. He is also (like Tohti) reportedly in a Chinese prison. I call it “a fierce and brave cry of moral repugnance.”

Also, why are you questioning on him not talking about his mother? What kind of point are you trying to make by raising that question?

I am not questioning him, only wondering why, in such an autobiographical piece, there is no mention of her or other members of his family, aside from his father.