Sundance Film Festival Review: “Kim’s Video” — Lost and Found?

By David D’Arcy

Kim’s Video is quixotic in a nutty way — in an old Indie style — that is more refreshing than it is nostalgic.

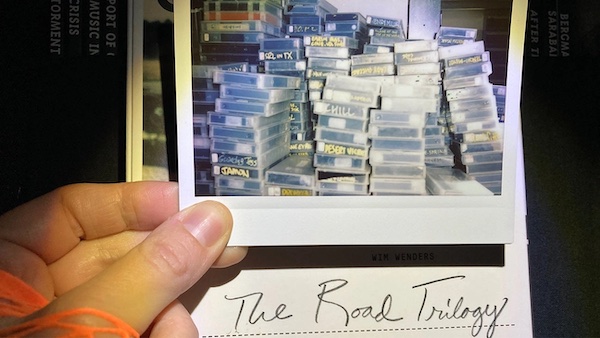

VHS tapes from the Kim’s Video collection. From Kim’s Video. Photo: Carnivalesque Films.

The annual pilgrimage to Sundance was in-person again this year. After the first days of hectic celebrity-chasing and SUV gridlock, the festival eased into a rhythm as the snow fell steadily over Park City, Utah.

One of the most entertaining films for me, all the more because it didn’t sacrifice any of the edge in its tale of shameless corruption, was Kim’s Video, directed by Ashley Sabin and David Redmon. Mondo Kim’s was a landmark store on 8th Street (St. Mark’s Place) in the East Village of New York that carried some 50,000 film titles. Many of them were not commercially available; there were movies that had been bootlegged or kept in circulation long after the films were legally available, if they had ever been available at all. If you wanted to see Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1987), Todd Haynes’s notorious bio-pic told with and by Barbie dolls, this was a place where you could rent it, even though neither Haynes nor his distributors had the rights to distribute it.

Kim’s wasn’t just a store, it was a library, and a unique one. Yet when rents soared in the gentrified East Village, its tall and mysterious owner Yongman Kim decided to close the place in 2008. Kim, who first operated a laundry that had rented out videos before he opened his store, tried to save the archive. Aided by an adviser (of questionable judgment), Kim connected with Salemi, a hilltop town in Sicily that was rebuilding after being flattened by an earthquake. Kim was promised a building for the videos, free rentals for members of the store’s video club, and even lodging for members who visited Salemi. Too good to be true? Good guess. There was a sane alternative — NYU had offered to take the videos.

Redmon and Sabin evoke the colorful and homey New York bohemia of Kim’s era. We are told that Joel and Ethan Coen still owed a stiff overdue fee when the place shut down. Redmon, who provides a subdued I-can’t-believe-this narration, can’t contact anyone in Salemi. He heads to Sicily to track down the archive. Hence the conundrum – you used to be able to find anything at Kim’s, and now you can’t find Kim’s at the place where its archive was supposed to be preserved in perpetuity. Here’s another way to think about it: Italian sleuths with the Carabinieri (Italy’s national police) scour the art galleries and the auction houses for antiquities smuggled abroad, and here an American with a camera is breaking into offices in search of videos that had been bootlegged in New York.

Kim’s Video looks like a Sundance documentary from 25 years ago — cheap and slapdash, infused with the weirdness of a movie by Michel Gondry, with a tenth of the budget. Still, its mission is honorable; the film is quixotic in a nutty way that is more refreshing than it is nostalgic.

When Redmon arrives in Salemi, no one knows a thing about Kim’s and no one speaks English, not even the people at the tourist office. That is, no one except for the chief of police, who has plenty of time to tell the filmmakers – in broken English – that he knows nothing.

Redman locates Kim’s trove in a nondescript unidentified renovated building – much of the town looks like a nondescript renovation – where the films are stacked up and collecting dust. So much for preservation.

The camera exposes what’s become of Kim’s in Sicily, but we’re still only a third or so into the film.

Redmon’s odd quest isn’t over, even though the locals brush him off like a fly. Salemi’s economic resurgence — as well as what looks like its hijacking of Kim’s archive — turns out to be managed by the Mafia. This is Sicily, after all, yet you might have thought that the mob had bigger fish to fry, more on the scale of The Godfather. Taking on the Mafia in Sicily would seem to be a dangerous gambit, if it weren’t such a comedy of errors.

The Mafia chief is Giuseppe “Pino” Giammarinaro, a man known to law enforcement. He seems to have diverted the money meant for Salemi’s recovery, including the cash that would have gone to finding a home for Kim’s video archive. The invitation to move the store became part of a front, a scheme for a Mafioso to embezzle funds from a small town, literally stealing from widows and orphans who might have wanted to see obscure movies on video. When confronted by Redmon, Giammarinaro doesn’t know a thing about it. The government investigator who does know ‘happens’ to die in the middle of the night. It’s not just comedy.

Giammarinaro has a friend in the mayor of the town, Vittorio Sgarbi, a career academic and art historian whom most of Italy knows as one of the participants at Silvio Berlusconi’s bunga bunga sex parties. Sgarbi was also a celebrity to Italians for his daily television show of many years, a one-man rant on the day’s obsession. In Salemi, when Redmon catches up with him, the insouciant Sgarbi claims that he doesn’t know about Kim’s archive. He says he‘s in Salemi for the opening of a new Museum of the Mafia. Another place to stash earthquake recovery money? Sgarbi shrugs. If you called it a Museum of Law and Order, he says, no one would come.

Redmon eventually realizes that he’s in over his head, given that the police chief is on the side of the cultural money launderers. In real life, as in the movies, the mob inevitably punishes the nuisances who get in its way. No spoilers here. Let’s just say, with a nod to Chinatown, that it’s Sicily, Jake.

Justice? Kim’s video archive is now under the control of Alamo Drafthouse Cinema — an improvement. Back in Italy, Vittorio Sgarbi has a cabinet position overseeing culture in the new fascist government in Rome. Somehow, I’ll bet he shows up, with his same shrug, if and when and wherever the film premieres in Italy. He’s the talent, after all.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: Ashley Sabin, David D'Arcy, David Redmon, Kim’s Video, Sundance Film Festival, video documentary, Video Store

Great story, but you sure could have used better images to illustrate it.

Hi Mark,

I agree, but those are the only images that were available from the film.