Classical Album Review: Wadada Leo Smith: String Quartets Nos. 1 – 12, played by the RedKoral Quartet and Guests

By Steve Elman

Over the past year, I’ve delved into the most significant body of work for string quartet ever written by a composer whose primary identity with the public is as a jazz musician. Here’s how to begin your own encounter with important facets of the work of an artist whose name you ought to know.

What should a listener do when confronted with a set of twelve string quartets written by a major figure in modern music – twelve pieces (in almost thirty separate movements) that, with two exceptions, have never been recorded previously and represent an important new cycle in the string quartet repertoire?

What should a listener do when confronted with a set of twelve string quartets written by a major figure in modern music – twelve pieces (in almost thirty separate movements) that, with two exceptions, have never been recorded previously and represent an important new cycle in the string quartet repertoire?

Not to mention the fact that they represent the most significant body of work for string quartet ever written by a composer whose primary identity with the public is as a jazz musician. Nor to mention that this music has occupied the composer for more than fifty years of his artistic life.

This is the challenge presented to any listener by the beautiful boxed set of Wadada Leo Smith’s first twelve quartets, issued in May 2022 by TUM, that redoubtable little label from Finland led by Petri Haussila, as part of its celebration of Smith’s 80th birthday. To add more significance, all the music on the six CDs is played by the RedKoral Quartet (with a few guest artists), an ensemble created by Smith for the express purpose of learning and playing this music.

Attention must be paid.

What to do? This listener, anyway, decided to devote ‘Serious Time’ to engaging with pieces that are obviously of great importance to the composer. I have now lived with them for almost seven months, listening to each movement with both ears, giving myself time in between each quartet to allow the music to settle into my synapses, reading additional information about them (which is considerable) in online sources, and listening to other composers’ string quartets for perspective.

It has been a remarkable, ear-opening experience, and I’m writing now to give you some of the benefits of my effort and to encourage you to begin your own encounter with these important facets of the work of an artist whose name you ought to know.

The territory here will not be unfamiliar to classical listeners accustomed to the language of composers writing since the beginning of the twentieth century. Those who know Bartók’s work, for example, will find Smith’s quartets very approachable.

However, a listener who only knows Smith’s work as a jazz musician may be a bit nonplussed by his string quartets. They do not swing, although there is plenty of rhythmic energy in many of the movements. There are no “solos” given to any of the players in the jazz sense, although there are many moments in which an individual voice of the quartet takes the spotlight. The individual movements do not unfold like typical jazz compositions — theme, improvisations, theme. Instead, they develop in the way classical music compositions develop — sound elements are introduced, undergo development, and are brought to climaxes or resolutions. This happens in a single swathe of development in some movements, or several times in sequence in others, with new sound elements introduced and developed in their turns. A sense of finality emerges in the closing moments of each movement, and a full picture of the composer’s intentions becomes clear once all the movements of a work are heard.

Smith is careful not to use the word “improvisation” when he describes the techniques used by any ensemble playing his music, and this is particularly important in regard to the quartets, because this is music that has very specific goals. The composer intends the players to spontaneously create some parts of the composition, but they always must be aware of and aim for the goals he has set. He does not wish musicians playing his string quartets to take the traditional approach of jazz musicians, providing personal spontaneous takes on the music at hand; his goal is a creative fusion of intentions among the players, and between the players and composer.

To appreciate this music, jazz people will have to have patience – and their patience will be rewarded.

A new listener in either camp should best begin, I think, with Smith’s String Quartet No. 9 (As of this writing, this is not hearable on line, but some examples of Smith’s string quartet writing can be heard without cost. See More below.) It has no general subtitle, but its intentions are clear. Its first movement is named for Ma Rainey, “the Mother of the Blues.” The second is named for Marian Anderson, the Black contralto known for her stage performances and recitals, and especially for a 1939 open-air recital on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, after the DAR prevented her from singing in their Constitution Hall because of her race.

Wadada Leo Smith directing one of his larger ensembles. Photo: Michael Jackson.

These inspirations provide you with signposts — but you should not expect direct quotations from blues tunes or spirituals, familiar chord sequences, or regular rhythms. What each movement has is a flavor, an aroma, an aura of the musics that inspired the two women who are named. Each movement is strongly cohesive, showing Smith in full command of his powers as a composer. There are many lines of great lyricism and flowing passages with long rests that give you time to think and to savor. The first movement has a remarkable moment where the individual string voices gradually cohere to form a single resolving consonant chord, with the same resonance you might feel at the end of a blues chorus. The second has another, where the cello “sings” after the fashion of a gospel soloist and the other voices then come in, almost like a choir.

This quartet has the potential to serve as a point of entry into Smith’s quartets for a new listener, much in the same way that Dmitri Shostakovich’s Quartet No. 8 became the point of entry for many listeners into his magnificent cycle of fifteen.

Once you have accustomed yourself to Smith’s musical language in No. 9, I’d recommend going on to Quartet No. 10 (“Angela Davis: Into the Morning Sunlight”), Quartet No. 6 (“Prayer in the Garden of the Hejaz”), and Quartet No. 12, with movements titled “Billie Holiday, 1915-1959” and “Pacifica.” Eventually you will want to hear them all.

Each quartet has a distinctive character, but Smith’s language remains consistent throughout, more confident beginning with No. 3, and, in my opinion, reaching full flower with the arrival of No. 9.

When Smith puts a name on a movement (as he does in both movements of No. 9) or a title on an entire quartet (as he does with Nos. 7 and 8, named for species of desert plants) , he is not suggesting a detailed program or even a strong connection between the music and its characterization. In fact, some of this quartet music may have existed before its naming — much as happened with George Russell’s monumental work, “The African Game.” Russell told me that, as he wrote it, the music began to suggest a programmatic framework rather than vice-versa.

Rather than looking at the titles, a listener should engage directly with the music first, see how it makes them feel, and only then reflect on what additional resonances the titles or names may suggest.

One of the reasons this set has such integrity is that each of the works is played by members of the RedKoral Quartet, an ensemble of string players who are individually accomplished as well as adept as an ensemble.

Shalini Vijayan, first violin, is a member of the Lyris Quartet and has performed as part of Southwest Chamber Music. Mona Tian, second violin, is a member of the Los Angeles-based new music group WildUp. Andrew McIntosh, viola, is a solo artist and composer in his own right. Ashley Walters, cello, also has an active career as a conductor, and she directs the Ventura College Symphony Orchestra.

This quartet also has stamina. The first ten quartets in this set were recorded over a four-day period in 2015, with the last two recorded over a three-day period in 2020. Their devotion to this music is obvious, and the quality of these performances — especially considering the marathon nature of the sessions — is outstanding.

Left to right: Ashley Walters, cello; Andrew McIntosh, viola; Wadada Leo Smith; Shalini Vijayan, violin; Mona Tian, violin. Photo: Kat Nockels.

The four musicians in RedKoral were hand-selected by Smith to play his music around 1996, when they were beginning their careers in Los Angeles. In addition, in five of the quartets, Smith has augmented RedKoral with guest artists who have also been trained in his methods, along with Pulitzer prize-winning composer Anthony Davis, who plays in Quartet No. 6. Smith himself plays on two of the quartets (Nos. 6 and 8). Still, in every case the string ensemble has the primary role.

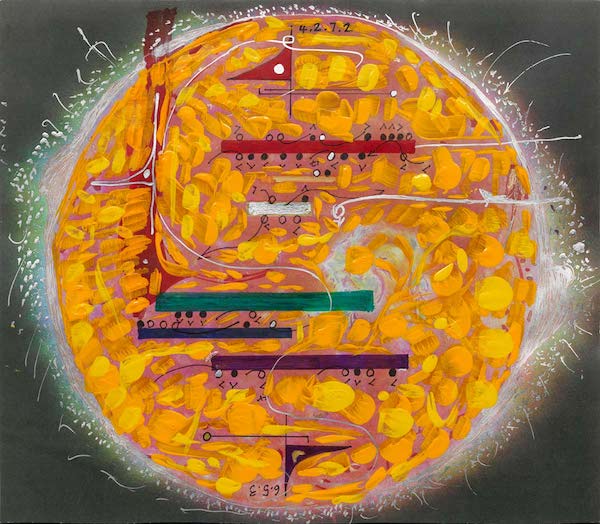

RedKoral and the other players have learned and absorbed the composer’s system of organizing and notating music, to which he gives the general name of Ankhrasmation. Much of his scoring — in all of his music, including the string quartets — includes visual symbols that the performers must learn to interpret. Those pictorial forms are pieces of visual art in themselves, with shapes and colors that convey particular meanings to players who understand his intentions.

Smith is not the first composer to look beyond the standard music notation system to get to the sounds he wants. He used standard notation extensively in his earlier quartets, and he still finds it useful for some elements. But Ankhrasmation is used extensively in the later pieces, and it gives performers more latitude than a written score would. He has described his process in interviews and on his website, and I have provided links below to online sources if you wish to investigate that process in depth.

An Ankhrasmation page from Wadada Leo Smith’s Symphony No. 1, Fall.

This set of twelve, written between 1965 and 2019, is just the beginning of Smith’s work in the medium. They may be thought of as a cycle of dedications and celebrations. They are complete as an artistic journey, and the current CD set should not by any measure be considered “unfinished business.”

But there are now five more string quartets, which Smith plans to record in 2023. Nos. 13 through 17, as they have been described in a variety of sources that quote Smith’s own descriptions, are envisioned to be inspired by milestone events in American life, and they promise to be the first works in a second artistic cycle.

Quartet No. 13 may be a transitional work. Smith says it is inspired by the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery. However, its movements (as performed in 2022) name Billie Holiday, Fred Hampton, and seven leaders of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the Black Panther Party, including Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, in the four movement titles. It is envisioned as an augmented quartet, with a soprano voice singing a text by Amiri Baraka.

Wadada Leo Smith. His trumpet is heard in Quartet No. 6 and Quartet No. 8. Photo: Jimmy Katz.

Quartet No. 14 is said to be inspired by the 14th Amendment, which extended the rights defined in the Constitution’s Bill of Rights to formerly enslaved people. That amendment also prohibits those who have sworn oaths of allegiance to the Constitution from holding Federal or state office if they are found to have been part of an insurrection against the United States.

Quartet No. 15 is said to be inspired by the 15th Amendment, which extended voting rights only to Black men — until all women won the right to vote with the 19th Amendment.

Quartet No. 16 is said to be dedicated to the passengers of United Flight 93, who fought against their hijackers in 2001 and prevented the terrorists from crashing that plane into the U. S. Capitol.

Quartet No. 17 is said to be inspired by the U. S. Capitol building itself, “recognizing it both an edifice of democracy and a site of gridlock and violent insurrection.”

These descriptions are surely flexible goals for Smith. As I explored the history of his quartets Nos. 1 to 12 on line — and this should be obvious from the beginning and ending dates of composition attached to each quartet in the notes to this boxed set — his works often go through extensive rewriting and rethinking before the composer declares them “finished.” Seven of the quartets in the set unfolded over a number of years — Quartet No. 1 took 17 years; No. 2 took 11; No. 4 took 14. On the other hand, three of them were completed in a single year, and Nos. 7 and 8 were both composed in 2011. So these sketches of the new five may only be indications of what the finished works will be like.

There is much more to be said about these works, and I have provided some further observations on their context in a separate post.

I want to offer one more observation, as one who has been profoundly moved by music throughout almost all of my life. What I miss in these performances is the intimacy and Soul (for want of a better term) that’s so clearly present in Smith’s music when he plays it himself or leads a group of jazz musicians. His smile and his essential belief in humanity, qualities I noted in my post about the Chicago Symphonies, are not as vibrantly expressed here as I would hope them to be. This is music on an intellectual plane with a powerful spiritual drive, but it does not wear its heart on its sleeve. Even in the movements named for his daughters in Quartet No. 11, I hear delicate and careful craft rather than the loving effusion one would expect of a father.

This is surely my problem much more than it is Smith’s, but in the five quartets that are to come, compositions that are projected to address issues that are so urgent and pressing in our America right now, Smith’s quartets have the chance to speak truth with the eloquence and passion the times deserve, and with the heart the times so desperately need. I hope that those quartets, and the interpretations of them, express more deeply the music in Wadada Leo Smith’s soul, and that they will reach new heights that these twelve quartets so beautifully promise.

“I’ve heard the sounds of the crickets, the birds, the whirling about and clinging of the wind, the floating waves and clashing of water against rocks, the love of thunder and beauty that prevails during and after the lightning — the toiling of souls throughout the world in suffering — the moments of realization, of oneness, of realness in all of these make and contribute to the wholeness of my music — the sound-rhythm beyond — beyond — is what I’m after through this precious and glorious art of the black man . . .” From Part 2 of Smith’s notes (8 pieces), reproduced on his website

MORE:

Full disclosure: I requested and received a promotional copy of this set. Now that I have heard the music, I would have gladly paid the full freight – and I can’t say that about most of the CDs I receive for free.

I am grateful to other writers, many of whom have interviewed Wadada Leo Smith about his string quartets. Links to some of their most interesting articles appear below.

I am also profoundly grateful to my old friend and radio colleague Doug Briscoe for providing his invaluable musicological advice in the final edit of this essay.

Wadada Leo Smith. Photo: Michael Jackson.

Wadada Leo Smith’s website has some striking photos, a very interesting personal essay on his musical philosophy and the language of his music, reproductions of Ankhrasmation pages from his scores, news of his awards and upcoming performances, and much more.

To sample Wadada Leo Smith’s musical language as it is manifested in his string quartets, a new listener might try hearing one of the two quartets that are available in earlier recordings, both of which can be accessed online.

I would first recommend hearing String Quartet No. 3, “Black Church: A First World Gathering of the Spirit” performed by members of Southwest Chamber Music in 2000 under the composer’s guidance. This was issued in Wadada Leo Smith / Southwest Chamber Music [“Composer Portrait Series”]) (Cambria, 2000). It is hearable on Spotify or via YouTube.

As with Smith’s other quartets, the title should not restrict your expectations. When another commentator noted that he did not hear much Black music in this piece, Smith said, “Black Church does have blues in it. It’s not blues form, but those phrases are definitely connected with my early childhood and blues music and church music.”

It’s also worth noting that the Southwest’s performance of Quartet No. 3 (recorded in 2000) is markedly different from the one given by the RedKoral in the new boxed set (recorded in 2015). The running times of the two recordings are different — the RedKoral’s is some six minutes longer. Also, in the 2000 performance, the Southwest plays the music without the movement divisions that Smith specifies in the RedKoral version, although there clearly are two parts in the earlier realization.

Comparing the two recordings, by the way, is yet another way to appreciate the nature of the music and the flexibility Smith gives the performers. You will hear features that are the same in both recordings, especially at the beginnings and endings of the movements. But alongside these similarities there are dramatic differences. It is remarkable that, despite those differences, the impacts of the two performances are consistent.

I wish that I could direct you to a streaming source for Smith’s String Quartet No. 9, which I found one of his most immediately approachable works. However, as of this writing, TUM and Smith have not opted for any of the music in this 2022 set to be available via Spotify or posted on YouTube. At one time, tidal.com offered nearly all of the twelve quartets for on-line listening, but those links have been deactivated, possibly at the request of the label or the composer.

In fact, TUM does not post samples of the music on any of its releases via its website. This is unfortunate, in my opinion. It would be particularly good marketing for the label to make at least one movement of String Quartet No. 9 available for potential listeners to sample, on the label’s website or possibly via Smith’s page on Bandcamp.com.

What’s an interested listener to do? Listen to the Southwest recording on line, and if the music speaks to you, then buy the set of twelve quartets. Even if you do not like all of the music, you will be supporting a noble effort and a great artist by spending about $90.

More useful information on Smith and the quartets:

Writer Ted Panken reprinted on his website an article that he wrote for Downbeat about Smith in 2017, which includes descriptions of Smith’s music at The Stone in New York City in April 2017 and portions of an interview with Smith.

The Guardian offered an interview with Smith conducted by Ben Baumont-Thomas, published September 23, 2012.

BOMB offered an interview with Smith conducted by John Corbett, in July 2016.

Violist Kennedy Taylor Dixon wrote a very informative paper following study and performance of Smith’s Quartet No. 3. (Kennedy Taylor Dixon, “Engaging with the Score: Wadada Leo Smith, Graphic Notation, and the Performer’s Perspective,” Master of Arts thesis, December 2021, Western Michigan University [Kalamazoo, MI])

A feature in the New York Times by Seth Colter Walls included interview excerpts and a reproduction of a page of the score from Quartet No. 11 (Seth Colter Walls, “This Trumpeter’s Legacy Also Includes Composing String Quartets,” New York Times, July 13, 2022).

This article also provides valuable insight: Brian Wise, “Wadada Leo Smith’s String Quartets Offer Players the Chance to Find Their Own Way,” September 19, 2022, from the September-October 2022 issue of Strings magazine

Jazz Weekly offered an informative review of the new set by George W. Harris from July 18, 2022.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included 10 years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, 13 years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

Tagged: Ankhrasmation, RedKoral, RedKoral Quartet, Steve Elman, String Quartets, TUM, Tum Records