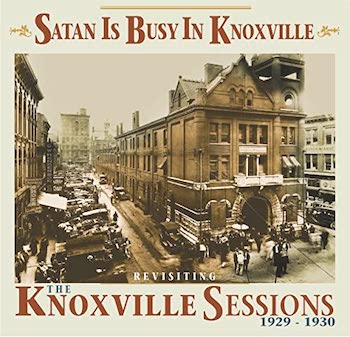

Album Review: “Satan Is Busy in Knoxville: The Knoxville Sessions, 1929 & 1930” — The Devil’s in the Details

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

Ted Olson continues bringing important location recordings of early American music back to light.

In the 1920s, the recording industry was looking to expand its customer base and appeal to a wider audience. To do this, they moved away from recording highbrow concert music and focusing instead on vernacular music from immigrant communities in Northern cities. However, between 1923 and 1931, some saw potential in the Southern market for “old-time” vernacular music. To capitalize on this opportunity to sell to an Anglo-American market, on-site recordings were made in the South. The records they produced were labeled “hillbilly” or “race” records, depending on the genre’s target market. Unfortunately, this approach not only reinforced racial and regional stereotypes, but obscured cultural reality, a trend that continues in the music industry today.

In the 1920s, the recording industry was looking to expand its customer base and appeal to a wider audience. To do this, they moved away from recording highbrow concert music and focusing instead on vernacular music from immigrant communities in Northern cities. However, between 1923 and 1931, some saw potential in the Southern market for “old-time” vernacular music. To capitalize on this opportunity to sell to an Anglo-American market, on-site recordings were made in the South. The records they produced were labeled “hillbilly” or “race” records, depending on the genre’s target market. Unfortunately, this approach not only reinforced racial and regional stereotypes, but obscured cultural reality, a trend that continues in the music industry today.

Ted Olson is a professor of Appalachian Studies at East Tennessee State University and has been working to present an accurate and un-exaggerated representation of these early recording sessions, which produced foundational artifacts in the history of American music. He has collaborated with historian Tony Russell and Bear Family Records, an independent German record label, to release box sets of three of these sessions, remastered: The Bristol Sessions 1927-1928 – The Big Bang Of Country Music (2011), The Johnson City Sessions 1928-1929 – Can You Sing Or Play Old-Time Music? (2013), and The Knoxville Sessions 1929 – 1930, Knox County Stomp (2016). He has followed each box set with condensed selections from each session under the titles We Shall All Be Reunited (2020), Tell It to Me (2019), and now Satan is Busy in Knoxville. As I noted in my review of We Shall All Be Reunited, Olson’s “expanded view gives us an intimation of what went unrecorded, the communal voices that inspired the music.” If your local library doesn’t have copies of each of these, it definitely should.

Satan is Busy in Knoxville brings us 27 of the total 99 recordings in existence (all available remastered in the box set). They are from the Brunswick/Vocalion sessions which took place in Knoxville in 1929 and 1930. Besides Olson’s detailed notes, there are also essays by Knoxvillian musician/storyteller James ‘Sparky’ Rucker and Jack Neely of the Knoxville History Project. One of Neely’s pieces sets the scene of the recordings, describing the city of Knoxville in the summer of 1929 and spring of 1930. It was a city in transition, mainly industrial with a small but growing suburban culture. Many factories were in decline and the Great Depression was affecting the city. Prohibition was in effect; in response, bootleggers and speakeasies were prevalent. The city was racially segregated, though Knoxville College enjoyed national prestige as a Black institution. The Great Smoky Mountains were becoming more accessible to tourists and attracting more attention, while newspapers, radio stations, vaudeville houses, movie houses, and, increasingly, phonographs were rapidly changing the city’s culture. Neely’s second essay is on Sterchi’s, the Southern furniture chain based in Knoxville that seized on the opportunity to sponsor the Brunswick and Vocalion recording sessions in hopes of pushing phonograph sales in their stores.

Rucker, too, helps set the scene by describing the events during the “Red Summer” of 1919, a time of racially-inspired uprisings around the US that hit Knoxville particularly violently. He also recounts his 1976 meeting with Tennessee Chocolate Drops members Carl Martin and Howard ‘Louie Bluie’ Armstrong, whose “Vine Street Rag”’ and “Knox County Stomp” appear on the album. These are important documents of early Black stringband music. Neely’s third piece has some thoughts about the mysterious Leola Manning, whose “Satan is Busy In Knoxville” gives its name to the compilation. The song’s powerful lyrics center on two murders that took place on February 22, 1930. The first was of a White man killed by a Black robber; the second was of a Black woman whose throat was slit. The motives for these homicides are lost to history; the suspicion is that the latter killing was in racial reprisal for the first. The song tells us that while we may not know the truth behind the killings, “the Good Book says they’ve got to reap just what they sow.” Those words echo down to today; they are a reminder that the pain of history remains until all accounts are settled. Manning used the session to decry the evils around her, yet told no family members about the recordings. Manning was described by her daughter as a religious leader in her community, which leaves us to wonder what was behind this foray into what many Black Christians of the time would have considered the Devil’s music.

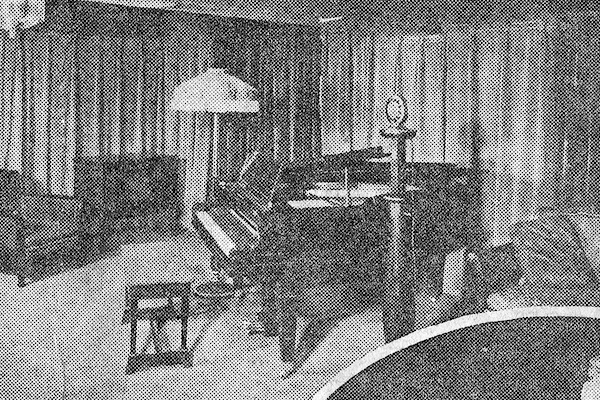

The St. James Studio. Photo: The Knoxville Mercury.

Other stand-out moments in the release include “I’m Sad and Blue” by the Perry County Music Makers, a track that features the zither, a German instrument not commonly connected to early American music. That group’s origins in western Tennessee also set it apart from the stereotype that rural music was mostly from the mountains. Hays/Hayes Shepherd’s appearance — as the Appalachian Vagabond — in “Peddler And His Wife” shows us how the Knoxville sessions shaped our understanding of the region’s recorded history. The role of technology in cultural transmission is also highlighted when we consider the creative process of the Tennessee Ramblers’ “Garbage Can Blues“, a product of that family-band’s attempts at a rendition of “That’s Where My Money Goes” as heard on local radio. Acts known to play live on radio like Cal Davenport & His Gang and Smoky Mountain Ramblers may also have been learning as much for the airwaves as on the street, where musicians like Robert A. Gardner and Lester McFarland were performing when they were not broadcasting. When old-time musicians today speak of learning from one of these early recordings, they’re repeating a folk process that the artists in these recordings also knew. Certainly Hesiod and Homer’s oral predecessors took advantage of literary technology at its inception!

Satan is Busy also challenges our ideas about racial musical boundaries of the time. The Wise String Orchestra, composed of the White Wise family, brings us the 1914 W.C. Handy composition “Yellow Dog Blues.” Then we have “Railroad Bill”, a song based on the tale of a Black Alabama train robber in the late 1890s. Bill’s story had developed into a popular folkway for both White and Black folks, though as I have written elsewhere Will Bennet’s version stands as an unadulterated Black depiction of the dangers, both real and imagined, which such an outlaw posed to the White establishment. He sings: “Buy me a gun just as long as my arm / kill everybody ever done me wrong / Now I’m gonna ride, my Railroad Bill.” The explicitness of the threat, and its connection to Whites’ anxieties regarding Black mobility, are jarring. We must evaluate what the ambiance of Knoxville and the attitude of Vocalion were like to permit such a recording.

It is an idiomatic expression in the South to say that “the devil sure is busy” – sometimes spoken by a person of faith, sometimes as one of our many ways to politely throw shade. Back in 2017, Pastor H.B. Charles Jr. of Jacksonville, Florida mentioned the idiom in one of his sermons, adding: “That’s the truth. But it is not the whole truth. I submit that the Devil is not the only one who is busy when bad things happen. God is also at work.” No doubt Satan was busy in Knoxville in the late ’20, but luckily God supplied a phonograph machine to make sure we wouldn’t forget it. This important collection of music is not only historically significant, it is also a window into the cultural, societal, and economic contexts that we have inherited from the time it was recorded. The compilation and essays provide a deeper understanding of the state of the music industry and of society in general. Essentially, the subject is the human condition and the ever-fascinating interactions between art and technology, community and individuality, happiness and suffering.

Jeremy Ray Jewell hails from Jacksonville, FL. He has an MA in history of ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. His website is www.jeremyrayjewell.com.