Visual Arts Review: Venice Through American Eyes — At the Mystic Seaport Museum

By David D’Arcy

The allure of Venice, as crafted by Venetian artisans, seduced American artists and collectors, who traveled across the world and brought back their prizes to American homes and eventually to museums.

Sargent, Whistler, & Venetian Glass: American Artists and the Magic of Murano, at the Mystic Seaport Museum, Collins Gallery, Thompson Exhibition Building, Mystic, CT, through February 27.

Attributed to Ercole Barovier (1889–1974) or Nicolò Barovier (1886–1953), Mosaic Glass Goblet, c. 1914–28.

For centuries Venice has lured visitors in search of a place that never seems to change.

But Venice was changed by its visitors, especially by Americans and especially in the late 19th century, a time when the city’s weakened economy welcomed American demand for its historical wares: hand-made glass. And that industry fed into a centuries-old trade that, for better or worse, sustains Venice to this day: tourism.

The allure of Venice seduced American collectors, who traveled across the world and brought back their prizes to American homes and eventually to museums. That process, reflected in glass and art, some 115 objects, is revisited in Sargent, Whistler and Venetian Glass: American Artists and the Magic of Murano.

By 1859, after decades of Austrian rule, Venice was a crumbling version of its once-powerful self. Its spice trade had declined, as had its once proud shipbuilding industry. The city’s struggling glass industry needed markets. What had not weakened was the myth of the decadently romantic Venice, which drew travelers anxious to bask in the spell of European ruins. In 1838, the hugely popular French writer George Sand helped revive the city’s appeal with her short novel The Master Mosaic Workers, set in the 16th century (the era of The Merchant of Venice). Her protagonists were men who made and traded glass, especially on the island of Murano. The book excited readers throughout Europe. One was the lawyer Antonio Salviati, who in 1859 seized on an opportunity to acquire the struggling Murano glassworks. His plan was to export beads and glass to the world, and to its most important emerging economy, the United States.

One of his marketing strategies was to mine the past for glass designs from the Renaissance. His aesthetics were guided by whatever the market would bear — the American market, that is. On view in the show are delicate goblets shaped in the form of gleaming fish, urns with rhythmic swirls of color, monochrome designs in silver, and bowls in styles from the Roman Empire.

The exhibition’s massive catalogue tells us that, in 1881, the art critic and newspaper editor James Jackson Jarves gave some 300 glass objects to the new Metropolitan Museum of Art. Jarves stressed that the works were examples of form triumphing over function.

The highest aim of the Venetian artist was to overlook prosaic utility entirely in his glass; to invent something so bizarre, ethereal, light, imaginative, or so splendid, fascinating, and original in combinations of colors and design, as to captivate both the senses and understanding, and lead them rejoicing into far-away regions of the possibilities of an ideal existence.

Yet, when accepting a donation of Venetian glass in 1914, the Rhode Island School of Design’s museum director acknowledged that glass artists could veer into “over-decoration.” He cited a green bowl inspired by a 16th-century scale pattern, with a rococo stem so elaborate that it made the object almost impossible to hold. The more improbable, the better, these objects seem to be saying.

Goblet with Lace Design, c. 1870s.

Still, the works ended up in the Smithsonian Institution, where this exhibition originated, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, and at Stanford University, where Jane Elizabeth Lathrop Stanford hired Salviati’s firm to create mosaics for the university’s museum and chapel.

Once US tourism revived after the Civil War, Venice became an essential stop for American painters. John Singer Sargent and James Abbott McNeil Whistler came in 1879 and 1880 respectively. Each was drawn to more than the city’s elegance and charms.

Scenes of women stringing glass beads in dark workshops were part of the real everyday Venice, at least as Sargent saw it, as a place where citizens worked and lived among themselves. The artist even observed (or at least painted) what looked like intimacy there, in the painting The Sulphur Match (1882), where a swarthy bearded layabout and a grinning local beauty are flirting, a broken glass in front of them suggesting shattered taboos. (At the time it was easier for Sargent to paint Venetians indulging in guiltless libido than Americans.) Bear in mind that Sargent used models for these Venetian paintings, including for A Venetian Woman (1882), the catalogue’s full-length cover portrait — a groomed wholesome Venetian rather than a local at a tactile closeness.

Models or not, the earthy warmth of The Sulphur Match still comes through.

So does the chill in the painting Leaving Church, Campo San Cancio, Venice (1882). This is the outdoor Venice of shadowless public squares under gray skies, muted ocher walls, and women burying their faces in long black shawls.

Sargent also painted a sunlit neoclassical corner of the Church of San Stae, a grand structure, although the ochre building alongside this landmark is gutted, with a pile of what looks like trash in our line of vision. Other painters sought out remnants of grandeur in Greece and Rome, but Venice’s graceful decline in the years before Sargent painted San Stae ensured that there were plenty of decaying ruins around. He would also eventually also find time to paint rich Americans who gravitated there.

John Singer Sargent, Leaving the Church, 1882.

Whistler arrived in Venice in 1879, shell-shocked and impoverished, fleeing the wounds of a lawsuit that he filed and won in London against no less than the critic John Ruskin, author of The Stones of Venice. Ruskin wrote of one of Whistler’s gauzy dark London scenes called Nocturnes that he “never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.'” Whistler sued Ruskin for libel, but won a judgment of only one farthing. He went broke paying his lawyers.

In 14 months in Venice, Whistler completed mostly drawings and etchings, and only a few paintings, one of which was Nocturne: Blue and Gold, Saint Mark’s, which is shrouded in fog. Ruskin might have scorned this picture as he did the painting that triggered the libel suit in London.

Whistler’s etchings of Venice range from busy views from above, of the Riva degli Schiavoni extending eastward along the water from St. Mark’s, to crumbling portals opening into dark alleys or scenes of women old and young stringing beads outdoors. This is not the grandeur of J.M.W. Turner, whom Ruskin championed, but the everyday labor of the city’s major industry, glass. It was now rubbing up against Venice’s newest industry, tourism.

From its central core of images by Sargent and Whistler, the exhibition spins off in multiple directions — to other American artists observing Venice, to glass that is delicately elaborate and weird, to designs in lace inspired by patterns in glass, to Venetian references turning up at improbable times and places.

Twenty glassblowers and a team of assistants from one firm in Murano were at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Salviati’s own firm had a display at Italy’s national pavilion. Twenty Venetian gondoliers and 60 pilots were on hand to take visitors around the fair’s waterways. And no less an artist than Winslow Homer painted them at work in a shimmering monochrome, The Fountain at Night, World’s Columbian Exhibition (1893), loaned to the Mystic show by the Bowdoin College Museum of Art.

Maurice Prendergast, Fiesta Grand Canal, Venice, c. 1899.

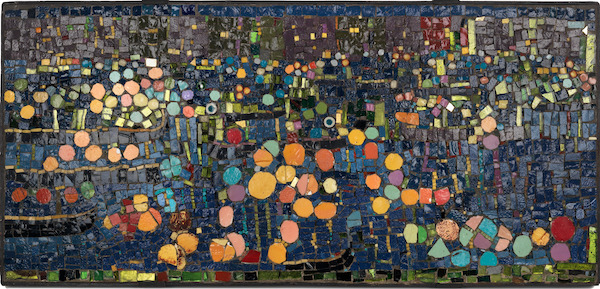

Homer’s painting, once you get over the surprising subject, is a work of quiet elegance. Works by Maurice Prendergast are more spectacular than serene — one is a glass and ceramic mosaic of radiant lanterns on gondolas crowding together and another is an oil painting that uses a mosaic effect to evoke the kaleidoscopic parasols of visitors massed along the Riva degli Schiavoni. Prendergast’s pictures win the trifecta — an American artist creating uniquely Venetian scenes with decidedly Venetian materials.

Just as memorable is Murano 1907, a view of the island seen from a distance by Hermann Dudley Murphy, in which sky and sea, in a near-uniform blue shade, are only distinguishable by a faint horizontal strip of island that bisects the picture. Calling this scene serene, the quintessential Venetian adjective, understates the picture’s hypnotic effect. A closer look reveals more. Amidst the clouds of fog you can glimpse tiny white patches. They mark the sites of glass furnaces: the lights reflect like sparks off the water. The campanile on the island emits a pink glow, as if it were a delicate glass object. What first feels like a nocturne inspired by Whistler radiates as if the muted colors were more glaze than paint.

There are curiosities, such as the mosaic portraits from the Salviati studio of Theodore Roosevelt and of Mrs. Leland Stanford of California, a collector with a commitment to Venetian glass and the resources to acquire boatloads of it. Given the brazen entrepreneurship of Salviati and his competitors — driven by the willingness of Americans to buy (sometimes with more love than judgment) — oddities like these should be expected.

By World War I, American ardor for Venetian glass slackened as tourists stayed away. Venice found itself facing a greater threat. The Futurists, artists and cultural militants who saw themselves as a force of history — with Benito Mussolini as their battering ram — called for the demolition of dusty old Venice, including the burning of gondolas. As a movement, Futurism sputtered, partly because one of its leading talents, the painter and sculptor Umberto Boccioni, was killed training for WWI in 1916. He was thrown from his pre-industrial horse and trampled. As fate would have it, Mussolini’s disdain for Venice gave way to other priorities; he only got so far as to punish a Communist neighborhood by filling in a canal to create the Via Garibaldi – an ungainly road in a city of canals.

Now Mussolini’s spiritual heirs are back in power. So far, Venice is not in their sights. It’s reassuring that the city once threatened by neglect can focus on new perils, such as the impact of mass tourism and the rising waters brought to new heights by the climate crisis.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: David D'Arcy, James Abbott McNeil Whistler, John Singer Sargent, Murano glassworks