Book Review: Mr. Wilder, Are You Ready for Your Closeup?

By Preston Gralla

A funny, bittersweet novel by British writer Jonathan Coe portrays the great American film director Billy Wilder on the downside of his career.

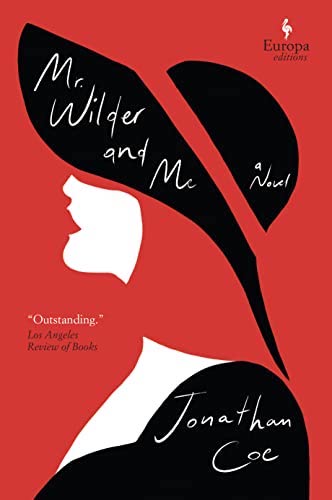

Mr. Wilder and Me by Jonathan Coe, 256 pp, Europa Editions. Hardcover, $27

The list of good novels about movie directors is not a long one. You won’t find much beyond the over-the-top satiric Blue Movie by Terry Southern, and Diane Spiotta’s Innocents and Others, which is more about relationships than it is about movie-making.

The list of good novels about movie directors is not a long one. You won’t find much beyond the over-the-top satiric Blue Movie by Terry Southern, and Diane Spiotta’s Innocents and Others, which is more about relationships than it is about movie-making.

But now the British writer Jonathan Coe has written Mr. Wilder and Me, a sometimes-funny, sometimes-melancholy, but always moving novel about the great American director Billy Wilder on the down-slope of his career.

Coe has long been fascinated by movies, dating at least to his 1994 novel The Winshaw Legacy: What A Carve Up, a strange, comedic novel in which the real-life British 1961 black horror-comedy “What A Carve Up,” plays a central role. Coe also wrote a screenplay of one of his novels, Dwarves of Death, which was turned into a movie, and has written biographies of Humphry Bogart and Jimmy Stewart. His writing is often suffused with the sardonic comedic tone that Wilder deploys in such celebrated movies as The Apartment, Sunset Boulevard, and Some Like It Hot.

This book, though, is not so sardonic. Rather, it’s human, poignant, and often melancholy. It is filled with a dusky, post-sunset light, even though much of the narrative is set in the Greek islands where Wilder is filming his second-to-last movie, Fedora. He’s on the downside of his career, and unable to find Hollywood financing because the money is all going to a younger generation. The year is 1978, only three years after the success of Steven Spielberg’s Jaws made Hollywood beholden to spectacle rather than the kind of human-sized stories that Wilder told. He was forced to find financial backers in Germany, an irony not lost on the Jewish, Austria-Hungary-born Wilder who spent his young adulthood in Berlin before fleeing when Hitler came to power in 1933.

The novel is historically accurate, and Coe captures Wilder’s dark wit throughout. Just one example: Wilder’s mother disappeared in the Holocaust; Wilder was never able to confirm her fate. In the book, Wilder holds a press conference in Munich after finishing filming Fedora. When he’s asked whether he thinks the movie will be a hit, he answers, “If it’s a huge success, it’s my revenge on Hollywood. If it’s a flop, it’s my revenge for Auschwitz” — something Wilder did say during that press conference in real life. (There’s an appendix that lists the sources for whenever the book uses a quote from Wilder.)

The book is narrated by an older woman, Calista, who is looking back to her naïve youth when she accidentally fell into the orbit of Wilder and his longtime co-screenwriter Iz Diamond. Much of the pleasure of the book comes from her wide-eyed fascination with them and their milieu, starting with dinner at the Beverly Hills Bistro restaurant, an island of apparent European luxe in the midst of philistine Los Angeles. In fact, though, she discovers that all of the Bistro’s fittings — bar, lights, paneling and more — were taken from the set of Irma La Douce, Wilder’s comedy about a Parisian prostitute. Silver-screen dreams once again replaced the real thing.

From there, the book moves to the Greek islands for shooting Fedora. Along the way Calista sheds her naivete and learns more about Wilder’s fading place in the film world. She also discovers his not-always-easy beginnings, starting with his youth as a taxi dancer in Berlin hotels — barely one step above a gigolo, he was paid to dance with women, typically many decades his elder, and many sizes larger than him.

Director Billy Wilder, Marthe Keller, and Michael York during the filming of Fedora.

He eventually reveals to her his life’s greatest tragedy: his mother vanishing, almost certainly into the Nazi death camps, leaving no trace or record behind. Wilder tells Calista about being hired after the end of the war by the US army to make a movie about the camps which would be shown throughout Germany to force Germans to see the horrors in which they had been complicit. He was supposed to piece it together from films taken by the Allies when they liberated the camps. He watches reel after reel, unendingly, always asking for more. He never made the movie, though; that’s not why he was riveted. He was, instead, looking for his mother among the survivors.

Nearly a half century later, he desperately wanted to make a movie of Schindler’s List, but his reputation had fallen so far that Hollywood turned to Spielberg instead. Wilder tells Calista about viewing the movie after it was completed: “When I saw that film … the scenes in the camps, the death camps … I wasn’t looking at the actors any more. I was watching the thing itself, while it was happening, and I realized I was looking for her. I was still looking to see if she was there.” That moment is a tribute not just to the depth of his loss, but to the power that movies held over him. Coe, by the way, didn’t invent Wilder’s reaction to Schindler’s List — the German director Volker Schlöndorff told him the story when Coe interviewed the director while researching the book.

Ultimately this is a novel not just for movie lovers, but for anyone who favors sharp writing, subtle wit, deeply portrayed characters, and the elegiac. It never delves into what Wilder thought about Fedora, a snakebit production and one of his lesser works. Even if he felt it was a failure, though, incisive readers will know exactly how he would have explained it away, with the line he gave to Joe E. Brown at the end of Some Like It Hot: “Well, nobody’s perfect.”

Preston Gralla has won a Massachusetts Arts Council Fiction Fellowship and had his short stories published in a number of literary magazines, including Michigan Quarterly Review and Pangyrus. His journalism has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Dallas Morning News, USA Today, and Boston Globe Sunday Magazine, among others, and he’s published nearly 50 books of nonfiction which have been translated into 20 languages.

Tagged: Billy Wilder, Europa Editions, Jonathan Coe, Mr. Wilder and Me