Visual Arts Review: Ukrainian Art Today — Crystallizing the Immediacy of War

By Kathleen Stone

These are individual expressions of how it feels to live in a war zone, not scenes of valiant fighters intended to recruit more combatants.

Don’t Close Your Eyes, at the New Art Corridor, 245 Walnut Street, Newton, through November 26. Eye of the Beholder, at the Grimshaw-Gudewicz Gallery, 777 Elsbree Street, Bristol Community College, Fall River through December 22. (All artwork is for sale, with proceeds to be shared 50/50 between the artist and a humanitarian organization).

Sketches of the War, Evgen Klimenko, 2022.

Russia’s war against Ukraine has drawn journalists and photographers from around the world. Much of their work is brilliant, and we have become all too familiar with its riveting, terrible detail. But Ukrainian artists who are enduring the conflict are also documenting the war in their own ways. Now, some of their artwork has made its way here. In it, the terror, anger, anguish, and hope that Ukrainians feel every day is crystallized.

This is a group show — the work of 26 artists exhibited in two locations. In Newton, approximately 50 drawings and paintings are installed in a corridor-long gallery at 245 Washington Street run by the New Art Center. In Fall River, almost 130 pieces hang in the Grimshaw-Gudewicz Gallery on the campus of Bristol Community College. It is a fool’s errand, I know, to write about only a handful of pieces, as though the few can represent the whole but, at a loss for a better way to describe what I saw, that’s what I will do.

Remember the time before February 2022, when Russia adamantly denied its intention to invade? Not everyone believed the lie. Oleksii Revika thought the invasion would come and, as far back as 2019, he began channeling his foreboding into intricate ballpoint pen drawings. One shows a farmer pushing a wheelbarrow on the edge of a vast field. Amid the orderly rows and the clean horizon line, the farmer may well feel at peace. If he only looked up, he would see a Russian helicopter flying between dark clouds and know what was coming.

When the war did come to Ukraine, there was hope that the country’s cultural artifacts might be spared. In pencil drawings with a sparse watercolor wash, Halyna Andrusenko presents statues wrapped in shrouds, a delicate rendering of all that hopeful wrapping and sandbagging citizens undertook early in the war. Karina Synytsia’s Mariupol Before the War shows lovely architecture — ornate cornices and Corinthian columns — that once dotted the city, now most likely gone.

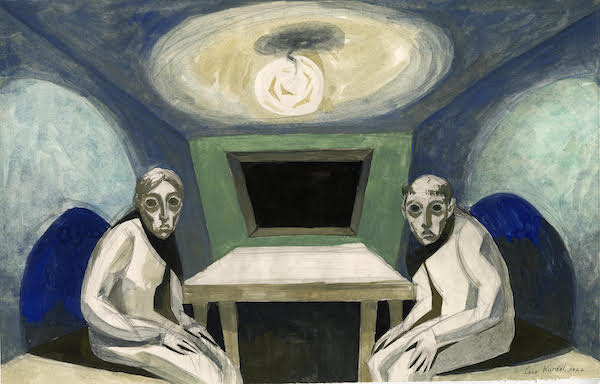

Shelter, Lena Kurzel, 2022.

What is it like to try to survive underground? Lena Kurzel’s Shelter gives us an idea. A couple sits at a bare table, single light bulb overhead. Their eyes are huge, black, frightened. They stare at us, frozen in a moment that will, if they are lucky, last until it is safe to emerge. Others are not so lucky.

Death is inescapably a subject of this art, and artists show it by various means. Ilya Yarovoy uses full color to capture a woman who has, for the moment, survived a roiling cloud of devastation. Her dark dress sets her apart from the red, yellow, and orange clouds that swirl behind her. But others have surely perished in the lethal firepower; her fingers, elongated and twisted, tell us so. More spectral images, in ghastly blue and pink, come from Olha Zaremba. A baby, mouth agape, and animals, dead on the ground or frozen in fear, convey cold terror.

When it comes to death, black and white can be as eloquent as color. In lithographs by Alisa Gots, we see what look like X-Rays of pockmarked skulls, with wide eye sockets and grimacing mouths. Ave Libertatemaveamor draws with black marker to show Russian missiles landing among freshly dug graves, a strong graphic with an Art Deco feel. Titling his work The Saviour of the Universe, he uses irony to poke the Russians. It’s another side of the cheeky resolve we have come to expect, starting with President Zelensky and extending to pilots in the sky with nicknames like “Juice.” Sometimes the resolve is angry, as in Valeriia Rybchenko’s drawings of fierce women who take tanks into their wide open mouths. Thus devoured, the tanks are removed from the battlefield. If only.

I Think Tomorrow Will Come, I Think It’s Too Late #2, Alisa Gots, 2022.

Sometimes it seems a miracle that we, at home in the United States, can see so much news footage from a hot war zone. Another miracle, I think, is that so much artwork has been shipped here from Ukraine. Accommodations had to be made, of course. Most of the works are small scale, and most are rendered in quickly applied mediums such as pencil, pen, watercolor and gouache. Some, like Evgen Klimenko’s drawings of wrecked buildings, have stray pencil lines and finger smudges, reminding us that these drawings, like most of the work now displayed in Newton and Fall River, were made on-the-spot.

In fact, immediacy is what sets this work apart from most other artworks about war. Think about some of the best known paintings. Uccello painted his Battle of San Romano several years after Florence won that battle in 1432. Meissonier was attached to the staff of Napoléon III, but he painted battle scenes in the studio, after the fact. Even Guernica, for all the anguish it conveys, was painted in Paris, shortly after Picasso heard about the bombing in Spain. Closer, perhaps, are the prints and paintings that Manet created based on sketches made at the scene. Or Goya’s prints, roughly contemporaneous with the era’s battles but not published until long after his death. Comparison might also be made to so-called combat art created by North Vietnamese artists during the American war in Vietnam. Made at the front, and sent home to bolster support, it was part of a coordinated propaganda effort. But I don’t think the same can be said about the art from Ukraine. These are individual expressions of how it feels to live in a war zone, not scenes of valiant fighters intended to recruit more combatants. The work is intensely personal and as varied as the artists themselves. When art is one’s calling, and one is surrounded by war, what else can one do?

Kathleen Stone is the author of They Called Us Girls: Stories of Female Ambition from Suffrage to Mad Men, published in March 2022 by Cynren Press. Her website is kathleencstone.com.

Thank you for such an insightful review of the works…This has expanded my viewing of them and I appreciate your deeply felt review!