Television/Music Review: Next at the Kennedy Center — A Joni Mitchell Songbook, on PBS

By Daniel Gewertz

I put Joni Mitchell on a short list of the most remarkable pop music artists of the ’60s and early ’70s. Longevity of excellence isn’t the point here, just peak incandescence.

Next At the Kennedy Center: A Joni Mitchell Songbook, on PBS, premiering Friday, November 18, 9 to 10 p.m.

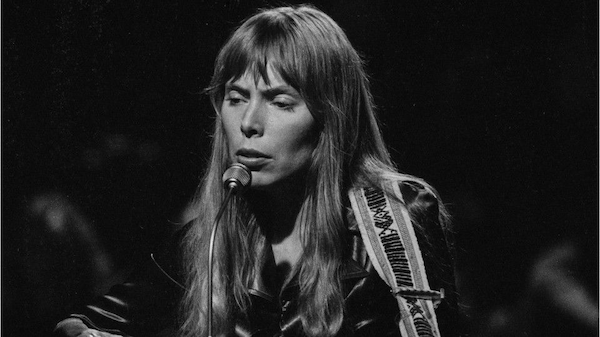

Joni Mitchell at the 2022 Newport Folk Festival. Photo: Paul Robicheau

Here’s the concept: the songs of Joni Mitchell reimagined by the 100 piece National Symphony Orchestra. To a Joni fan like myself, the idea doesn’t quite provoke fear, exactly: more like ennui. Intimacy is the first likely victim in such an official, sweeping project; Mitchell’s evolved personal vision is also endangered. So, to my fellow Joni adorers, let it be said right off the bat: “No worries.”

A Joni Mitchell Songbook — to premiere on PBS on November 18 as part of the Next at the Kennedy Center series — does not sacrifice intimacy for grandeur. It’s an even larger orchestra than the one Mitchell herself used when recording these same songs at the turn of the 21st century. With this Washington, DC, institution — best known for ceremonial state programs such as “A Capitol Fourth” — one expects elegance. This hourlong program of eight songs goes way beyond the expected. Some of the interpretations are far better than others, yet overall, the National achieves kinship with the highly personal Mitchell oeuvre; a few of the results are nearly magical. The credit has to go to arranger-conductor Vince Mendoza, and the canny way he interprets Mitchell’s merging of conflicting emotions. (Mendoza arranged her 2000 orchestral CD Both Sides Now, and won a Grammy for the title song.)

The singers, appropriate to the material, come from diverse fields. And they range from well- to little-known. It is no surprise that soprano megastar Renée Fleming is sublimely evocative, digging deep into “The Circle Game.” But, on the other hand, Jimmie Herrod turns out to be a revelation. Best known as a finalist on last year’s America’s Got Talent TV show, Herrod — who holds a BA in jazz studies — exhibits classical training and a musical theater background as well. His version of “A Case of You” may be the show’s high point: at times he drifts with ruminative ease, but his reading is always buttressed by an inner tension, an undercurrent that is oceanic. Even the line “go to him … but be prepared to bleed” is issued subtly: with an air of the inevitable more than the melodramatic.

(Herrod’s version of “Hejira” also tries for intense drama, but is less affecting.)

Nothing displays Mitchell’s career-long range better than Lalah Hathaway’s two selections. The R & B singer traverses the vituperative fury of “Sex Kills” as well as the openhearted self-questioning of “Both Sides Now” with equal soulfulness. She actually wrenches new meaning from the latter song’s youthful wisdom, more than either Mitchell’s original or Judy Collins’s mellifluous 1968 hit. While Collins sounded headlong in love with the lavish romantic poetry, Hathaway acts the part of patient explainer. As the lyrics darken, the singer is neither enraptured fool or premature cynic, but an honest, self-critical narrator. In these fine interpretive moments, one can imagine Mendoza’s guiding hand, sculpting the line readings, much like the touch of a theater director. Even as the 100 musicians surge to a climax, Hathaway halts her climb up the emotive ladder and murmurs the very last phrase with somber reflection: “I really don’t know love at all.” (In a personal touch, in the last verse she changes the word “life” to “love.”) As drummer Brian Blade says of Mitchell’s own 2000 orchestral version, “she’s not thinking of harmonics. She’s thinking of the unfolding story.” The same can be said of Hathaway.

The range of interpreters is gratifying. It honors the idea of Mitchell being a folk-pop genius with generous undercurrents of jazz and avant-garde in mid and late career. There’s the expressive Latino singer/guitarist Raul Midón on the breezy “Be Cool” and joining Hathaway on the nightmarish “Sex Kills.” Two songs feature Boston’s own Aoife O’Donovan, the folk-bred singer, formerly of the band Crooked Still. On “River” (the one song not collected on Mitchell’s two orchestral albums), her voice has grown larger yet more reflective than in her previous work. With O’Donovan’s heart on full display, the orchestra feels like a single lonely instrument. It is one of the hour’s three top highlights. When she sings “I made my baby cry” it is seriously expressive, utterly intimate.

The third absolute gem of the hour is Renée Fleming’s “The Circle Game.” One of Mitchell’s first famous songs, Fleming mentions that it was written for fellow Canadian Neil Young, to soothe Young’s upset about getting old. (He was turning 20!) With Fleming’s interpretive depth and restrained power — and the orchestra taking the song far beyond its simple folkie arrangement — one can sense what the youthful Mitchell once had in common with musical theater.

Like Dylan, Mitchell was first known via others singing her songs, namely Tom Rush, Dave Van Ronk, George Hamilton IV, her Canadian heroine Buffy Sainte-Marie, and slightly later, Judy Collins. Unlike Dylan, she didn’t have a powerful manager and big record label pushing her material, just her supportive (and slightly older) fellow folkies. Commercially speaking, “Both Sides Now” was her “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Yet despite the early spate of songs recorded by others, as her fame grew and her material became ever more personal, the songs proved less easy to interpret.

Joni Mitchell — her streak of albums from 1968’s poorly recorded Songs to a Seagull to 1976’s Hejira can only be compared to Dylan’s astonishing spree from 1963 (Freewheelin’) to 1967 (John Wesley Harding).

The best of the brief “talking heads” segments belongs to Graham Nash. He waxes eloquent about his former girlfriend’s overwhelming talents, and then bashfully admits that some lines in “River” can’t possibly be about anyone but him.

I’m not a fan of the show’s interpretation of “Woodstock,” and thought it wasn’t the best choice to kick off the show. It’s a tough one to pull off, the original being so personally entranced with the blissful social hopes for an emerging world, a paradise that never, of course, came to be. Mitchell’s dreamy majesty is replaced by O’Donovan’s more urgent reading. Is it a dated song at this point? One could imagine a version that reveres the old dream, but also recognizes the ensuing loss of innocence. This more insistent version simply misses the magic.

I put Mitchell on a short list of the most remarkable pop music artists of the ’60s and early ’70s. Longevity of excellence isn’t the point here, just peak incandescence. My list of luminaries include Dylan, Hendrix, maybe Lennon and Sly Stone. For a pure strain of sonic brilliance, Laura Nyro always comes to mind. Mitchell resides near the top of that list. The streak of albums from 1968’s poorly recorded Songs to a Seagull to 1976’s Hejira can only be compared to Dylan’s astonishing spree from 1963 (Freewheelin’) to 1967 (John Wesley Harding).

In the Kennedy Center show, only “Sex Kills” and “Be Cool” postdate 1976. Robert Glasper, the pianist/producer, extols Mitchell’s astounding changes over the years, transformations in voice, genre, and musical instinct. “Early Joni Mitchell and later Joni Mitchell sound like two totally different people,” he says, his voice expressing astonishment. “She’s two geniuses.” Yet it is also true that if it weren’t for Mitchell’s first eight years as a recording artist, the rest wouldn’t have become widely known. Among the eight songs in the Kennedy Center show, only one, “Sex Kills” might be termed edgy. Hathaway and Midón match the orchestra’s high dramatic portent.

By the time Hathaway and orchestra bring the program to a close with “Both Sides Now” and Hathaway sings the cautionary, ironic words, “Don’t give yourself away,” it is beautifully apparent that the orchestra has given themselves away to the journey. They’ve become bona fide keepers of the Joni flame.

For 30 years, Daniel Gewertz wrote about music, theater and movies for the Boston Herald, among other periodicals. More recently, he’s published personal essays, taught memoir writing, and participated in the local storytelling scene. In the 1970s, at Boston University, he was best known for his Elvis Presley imitation.

Tagged: A Joni Mitchell Songbook, Daniel Gewertz

I cannot wait to watch! and listen! I hope this will become if not available! That it will be saved to play again on TV!

After this Friday evening’s premiere at 9 p.m., I see listed repeats very early on Saturday morning, and next Monday at noon on WGBH.

i thought the show sucked. They took very emotional and direct songs sung by the best voice ever and turned them into jazzish drivel. No power. No meaning. No thought. That blond that opened didn’t even have the range and butchered it horribly. Painful, skreeching death. Only the black guy did one song well.

I absolutely agree with you! They picked very mediocre singers to sing her beautiful timeless songs. None of them had any range— including the blonde and the African American singer who was even worse and couldn’t even be bothered to get dressed up for the occasion

The loser woman in the suit. I would never have picked her to sing Joni Mitchell songs.

I came, I listened, and I was not conquered. I’d prefer to just dig out my carefully preserved Judy Collins and Joni Mitchell vinyls and give them another listen….

Interpretive freedom aside, this outing completely misses the mark. Start to finish, despite the polish and gushing sincerity of the vocalists, the boat never leaves drydock.

Will this be on PBS again?

Unfortunately,l missed it on Friday,

November 18th .

Love Joni Mitchell,Always and

BEYOND DEFINITI9N!

I am intrigued by these fierce, negative comments. To bitterly complain about the jazz elements seems to make little sense, since Joni herself was deeply influenced by jazz, even before her Mingus album. But I admit that, despite my having truly adored four of the eight performances, (“Circle Game,” “Both Sides Now,” “River,” “A Case of You”) I may have given short shrift to my dislike of Herrod’s “Hejira,” and could’ve mentioned that Raul Midon was merely adequate. As I said in my first lines, having doubts about this entire project — and then finding it far better than I feared it might be — it is possible I stressed the positive in my review. Lovely surprises are a critic’s joy, after all. I really should have said right off the bat that “Woodstock” was the worst thing in it, and a terrible choice to kick off the proceedings. I did say it later on. Ms. O’Donovan is a local Boston talent I have known, professionally, for many years, so it is plausible I “went easy” on her, without fully realizing it. But her mastery of “River” did win me over completely. (I suppose I could’ve legitimately criticized director Mendoza for placing “Woodstock” first in the program, and for his utter failure in guiding his singer toward a solid interpretation of that song. After all, I did praise him to the skies for his fine interpretive job elsewhere.) I didn’t mean to imply that Hathaway surpassed Mitchell and Collins on “Both Sides Now,” but rather, that she gave it new meaning. (I’ve heard Collins perform it many times in concert, and it remained strong, but also, not surprisingly, very similar to her big hit.)

Mitchell recorded with orchestra herself, and also, of course, recorded with modern jazz giants. And speaking of jazz geniuses: I thought the previous Kennedy Center show on Charles Mingus was a true failure: jam packed with long, frenetic, blandly excessive improvised solos. Mingus’ own studio work typically focused on the tunes themselves, and the propulsive, genius arrangements: the solos succinct, and woven into the whole with artistry. Also, the Mingus show’s spoken comments by the young musicians were bombastic. After that lame show, I was especially pleased that the Joni hour did not miss the mark, either in music or talk.

Listening to the program, I could not understand why so many of the vocals were in a canyon of reverb that disagreed with the beautifully present orchestra mix which made it difficult to hear the words clearly – a real problem when Ms. Mitchell’s lyrics are so essential to her incredible messages. I tried everything with settings at my end and concluded that it was simply a poor mix perhaps due to tech difficulties. What a shame.

Circle Game was well worth it, in my opinion. I’m glad I saw the review which got me to tune it.