Opera Album Review: An Enchanting New Recording of a Short Vivaldi Opera about … the River Seine

By Ralph P. Locke

Revelations continue: a composer best known for his sonatas and concertos (the Four Seasons) is a master of vocal music as well.

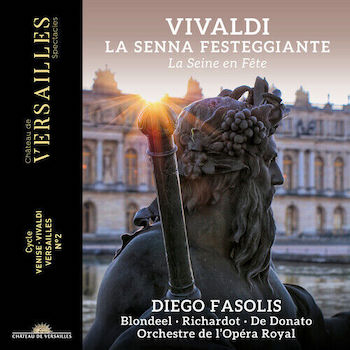

Antonio Vivaldi: La Senna festeggiante (“serenata” — or short, festive opera)

Gwendoline Blondeel, soprano; Lucile Richardot, mezzo-soprano; Nicholas Scott, tenor; Luigi De Donato, bass

Opéra Royal, conducted by Diego Fasolis

Chateau de Versailles Spectacles CVS064—81 minutes

Available on all major streaming services; to purchase, click here.

I’m delighted to welcome this recording, one of a number of recent releases of operas by Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741), long known primarily for the Four Seasons violin concertos and other instrumental music. But first, a warning: The cover of the CD announces the singers by last name only, thus listing one as De Donato. This inadvertently risks raising inappropriate hopes. World-renowned mezzo Joyce DiDonato could well have sung on this recording, but the singer with the somewhat similar family name is a young Italian bass who is quite fine but, by the evidence, something short of a superstar.

I’m delighted to welcome this recording, one of a number of recent releases of operas by Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741), long known primarily for the Four Seasons violin concertos and other instrumental music. But first, a warning: The cover of the CD announces the singers by last name only, thus listing one as De Donato. This inadvertently risks raising inappropriate hopes. World-renowned mezzo Joyce DiDonato could well have sung on this recording, but the singer with the somewhat similar family name is a young Italian bass who is quite fine but, by the evidence, something short of a superstar.

A serenata is a short opera, often composed for performance in a palace or other private residence to help celebrate an important event, such as a dynastic marriage or a visit from a foreign ambassador or clergyperson. The works were sometimes performed in the evening, outdoors (serenata comes from the Italian word for “evening”: sera), with few or no costumes, sets, and staging. Perhaps the singers sometimes held the notated music in their hands for ready reference, as tends to occur in “in concert” performances of operas today.

Many serenatas have mainly mythological characters, or symbolic ones, and that is the case of Vivaldi’s The River Seine Engages in Celebrations (as I might freely translate the title of the present work: the French equivalent is more compact, La Seine en fête). The three “characters” are the River Seine, Virtue, and the Golden Age. The role of the River Seine is sung by a bass, Virtue by a mezzo-soprano, and the Golden Age by a soprano. A tenor is brought in for three “choral” (i.e., here, four-singer) movements.

As the booklet-essay points out, La Senna festeggiante, like many other serenatas, avoids the emotional tangles that mark the opera librettos of the day. There is little or no anger, jealousy, or regret. At most, each character proclaims, with various kinds of imagery, the virtues of the River Seine and thereby of France and, by implication, its king (Louis XV).

Scholars have come up with numerous theories to explain why the work was originally composed, whether it did or did not get performed when and as originally intended (and, if not, why not), and whether it then got hauled out on some other occasion for which it suddenly seemed plausibly appropriate. Most of these explanations involve, naturally, Venice’s shifting relations with that same French king, Louis XV (or, sometimes, with England’s former Stuart rulers, who were Catholics and living in exile on the Continent).

Whatever the circumstances, the work is top-drawer Vivaldi and, according to musicologists, the most elaborate of Vivaldi’s eight serenatas (of which three survive in full). There are definitely French features to the work, such as movements in the style of a minuet or a louré. The arias (and two duets) are full of engaging melody and are nicely contrasting in mood. There is lots of coloratura, of course, but it never extends to disproportionate lengths: one is always aware of the words being sung.

Mezzo-soprano Lucille Richardot singing with the Opéra Royal in the recording of La Senna festeggiante. Photo: Pascal Mee

This is at least the fifth recording. Previous ones were conducted by Claudio Scimone (reportedly with slowish tempos), Rinaldo Alessandrini (reviewed here and here), Robert King, and Fabio Biondi. The bits that I have heard of the Alessandrini and Biondi recordings suggest that they are excellent renderings, but so is this new one, though of course it makes many different performance choices, as is part of the fun of the early-music scene nowadays. (The devoted audience members of the Boston Early Music Festival know what I’m talking about!) The sound quality is excellent, as one would expect, given that the venue used here is the famous small opera house at the Palace of Versailles. (See my review of a recording of Rameau’s Les Indes galantes made in that remarkable hall.)

I do wish that De Donato (as the River Seine) had fuller low notes, but I find myself wishing that of many basses and baritones nowadays. (See Conrad L. Osborne’s important book Opera As Opera, especially his discussion of “the disappearing low end” in recent singing; I reviewed the book here.) But De Donato is very affecting at other times, as in the encomium to Louis XV’s “mercifulness and sweetness” (track 27).

Diego Fasolis conducting the Opéra Royal in the recording of La Senna festeggiante. Photo: Pascal Mee

Gwendoline Blondeel is as gleaming and optimistic-sounding as one might wish the Golden Age to sound (though I have read even higher praise for Carolyn Sampson’s singing on the Robert King recording), and Lucile Richardot is a remarkably distinctive presence as Virtue, sometimes sounding a bit like a countertenor but holding my ear all the more because of this. (She was equally splendid on a recent recording led by cellist-conductor Ophélie Gaillard — see my review.) She, too, sounds thin on her lowest notes, but is otherwise so generous and insightful a singer that I am certainly happy they signed her for this project and not a singer who could pour sound out more fully down low.

The sung text (in Italian) and the scholarly essay (in French) are all given in German and English translations carried out by a firm called ADT International. Whoever did the translating made numerous inept choices in the essay, often simply transferring French words into English equivalents that look similar but do not carry the same meaning. “Important,” for example, specifically indicates size or expansiveness in French (that is, numerical quantity), which it does not necessarily in English. And it took me a while to figure out that “Bononcini’s attempted usurpation in London in 1731” refers simply to his having used musical material by another composer.

But the recording itself is a total delight, reminding us how much more there was to Vivaldi than the ever-present Four Seasons.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here by kind permission.

Tagged: Diego Fasolis, La Senna festeggiante, Lucile Richardot, Luigi De Donato, Nicholas Scott