Author Interview: Stephanie Schorow on “The Great Boston Fire” — Urban Conflagration

By Blake Maddux

“A lot of people don’t know about this fire today. It’s not really well known as part of the city’s history.”

“I think when you do any kind of history project,” journalist, author, and educator Stephanie Schorow told me in a recent Zoom interview, “you find all these little side stories that come off of it. And many of those side stories are as fascinating as the main story.”

“I think when you do any kind of history project,” journalist, author, and educator Stephanie Schorow told me in a recent Zoom interview, “you find all these little side stories that come off of it. And many of those side stories are as fascinating as the main story.”

Schorow has learned this firsthand by telling her adopted hometown’s history in numerous books that have investigated — to name just a few topics — the Cocoanut Grove nightclub fire, the Brink’s robbery, drinking and alcohol, and the Combat Zone (which I interviewed her about in 2018).

A Chicago native, Schorow’s many years as a Boston resident includes time as a reporter for the Boston Herald. Her latest work is The Great Boston Fire: The Inferno That Nearly Incinerated the City. Moreover, an updated version of The Cocoanut Grove Nightclub Fire was recently published in recognition of that tragedy’s 80th anniversary.

While the latter blaze was the deadliest such incident in Boston history (nearly 500 fatalities), the one that occurred 150 years ago is “considered one of the most expensive per acre [65 of which were destroyed] in American history, because of the amount of material that was consumed.”

Schorow has upcoming speaking engagements at the Boston Public Library (November 9), the Massachusetts Historical Society (November 10), and the Waterworks Museum (November 12).

In the meantime, here is a condensed and edited version of the conversation that we had via Zoom.

The Arts Fuse: Having written two previous books about fires in Boston, what inspired you to devote an entire volume to the Great Fire of 1872?

Stephanie Schorow: The absolute spectacle of it fascinated me. It’s just amazing. That was something that just captured me even more was the aftermath of the fire that everyone can see on the Boston Public Library site. Those pictures are just absolutely mesmerizing.

And the fact that a lot of people don’t know about this fire today. It’s not really well known as part of the city’s history. It was up until 1972 on the hundredth anniversary of the fire. The Globe did a whole big spectacular magazine supplement on it. Since then, not so much.

AF: Describe what happened in the first minutes of “the fire fiend” that contributed to its being more destructive than it might have been.

SS: The fire had been burning for about 20 minutes before the first alarm went off. It was seen around 7:00. The first alarm didn’t go out until 7:24. That’s quite a while, given that there were firehouses just a few blocks away.

There was a delay in responding to the fire, so it got a head start. And the buildings were just jam-packed with goods, such as wholesale cotton and leather. That’s why the fire is considered one of the most expensive per acre in American history, because of the amount of material that was consumed.

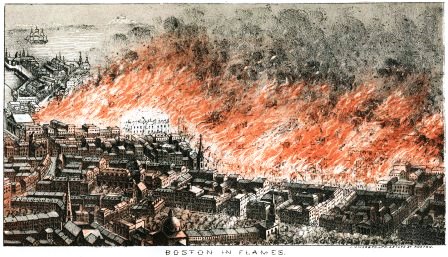

An artist’s rendering of the disaster from Russell H. Conwell’s History of the Great Fire in Boston (1873).

AF: Were the writings that appeared in the immediate aftermath of the fire useful to you?

SS: They weren’t as useful as you might think. They were good mostly for anecdotal things. They could not give me the actual death toll. They were full of color and anecdotes, but very few facts and figures.

However, one of the things that happened between my first book on it [Boston on Fire] and my second was that the commission report of the Great Boston Fire has been digitized. Digital sources are great because they’re searchable, so you can look for references for fact-checking.

It’s funny what people kept track of. One book detailed everything that was lost, right down to someone’s collection of medieval armor. But there was no really good accounting of all the casualties.

Journalist, author, and educator Stephanie Schorow. Photo: courtesy of the artist

AF: Was John Damrell in a Fauci-esque position as Chief Engineer of the Boston Fire Department?

SS: Absolutely. I had not made that comparison, but absolutely. I’m gonna steal that!

In his reports, he constantly pushed for improvements in the fire service. This included upgrading the water mains in downtown, which had grown so fast and shifted from a residential area to a commercial area. They had tall buildings and he was very worried about that. He was very worried about the use of wooden Mansard roofs, because he felt they were a fire hazard.

He wanted to have more firehouses stationed in the downtown, but because real estate was going up, there was some reluctance to devote more fire stations in that area. He was rebuffed, and according to his own account, he was told at one point, “do not magnify the wants of your department so much.” And another time he was told that if the water department wanted his opinion, they would ask for it.

AF: Damrell gave a presentation to city council after visiting Chicago in the wake of that city’s massive fire of the previous year. Was he right about basically everything in terms of what he warned about and recommended to prevent the same thing happening in Boston?

SS: Yes. He was basically right. Everything that he predicted could happen did happen. Had he been listened to, there would have been a big fire, but it would not have been this mammoth inferno that basically consumed a lot of the city. It took out 65 acres.

AF: If it were possible to superimpose the Great Fire on Boston today, which areas would have been affected?

SS: Starting at Downtown Crossing… if you were on Washington Street, one side of the street would have been okay, but if you looked across Washington toward the harbor, it’d be nothing but destruction right down to the water, which was closer than it is now. It would look like a nuclear holocaust. People couldn’t even find their businesses.

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who regularly contributes to the Arts Fuse, the Somerville Times, and the Beverly Citizen. He has also written for DigBoston, the ARTery, Lynn Happens, the Providence Journal, The Onion’s A.V. Club, and the Columbus Dispatch. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife and five-year-old twins — Elliot Samuel and Xander Jackson — in Salem, MA.