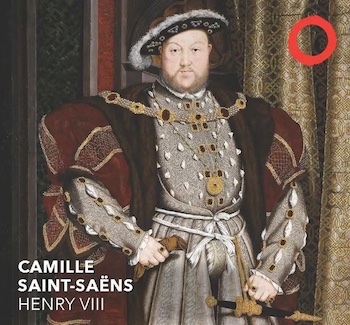

Opera Album Review: Odyssey Opera’s Invaluable World-Premiere Recording of Saint-Saëns’s Complete “Henry VIII”

By Ralph P. Locke

Gil Rose’s team, headed by an incandescent Ellie Dehn as Catherine of Aragon, should help bring this major work back to the world’s opera-house stages.

Saint-Saëns: Henry VIII

Ellie Dehn (Catherine of Aragon), Hilary Ginther (Anne Boleyn), Yeghishe Manucharyan (Don Gomez de Feria), Michael Chioldi (Henry VIII)

Odyssey Opera, cond. Gil Rose

Odyssey Opera 1005 [4 CDs] 224 minutes

To purchase, click here.

Henry VIII has paced across Boston stages several times in the recent past, in productions of Shakespeare’s play in 2013 and 2014 and in the well-received musical Six (at American Repertory Theater, 2019). Well, there’s an important opera about that much-married king and the first two of his six wives, and it, too, got performed in the Boston area in 2019, thanks to Gil Rose’s enterprising Odyssey Opera. Even better, the version that Rose used restored substantial scenes and segments that had been cut in previous productions and recordings.

Henry VIII has paced across Boston stages several times in the recent past, in productions of Shakespeare’s play in 2013 and 2014 and in the well-received musical Six (at American Repertory Theater, 2019). Well, there’s an important opera about that much-married king and the first two of his six wives, and it, too, got performed in the Boston area in 2019, thanks to Gil Rose’s enterprising Odyssey Opera. Even better, the version that Rose used restored substantial scenes and segments that had been cut in previous productions and recordings.

That performance, recorded live in the New England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall, has now been released on the BMOP label (named for the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, Rose’s other main organization). The four-CD set, available also as a digital download, is one of the major events of the year for classical record-collectors and opera lovers everywhere.

An opera that takes place at a royal court provides multiple opportunities for moments of grandeur, passion, and, yes, hypocrisy and underhanded manipulation. Saint-Saëns’s opera about Henry VIII, his first wife Catherine of Aragon, and the woman who would replace her, Anne Boleyn, seizes all these opportunities expertly.

Henry VIII is the second most-performed opera by Saint-Saëns, after the widely loved and oft-recorded Samson et Dalila. It can be seen on a commercially available DVD (with Michèle Command as Queen Catherine; also CD) and a pirated video on YouTube (with Monserrat Caballé, singing grandly but a bit flat a lot of the time). A fine recording from an unstaged performance at the Bard Music Festival is available (download-only). It features Ellie Dehn as a splendid, touching Catherine, Jason Howard in fine voice as Henry VIII, the remarkable Jennifer Holloway as Anne, and John Tessier, an idiomatic French stylist, as Don Gomez. Seek and you may find a way to hear earlier performances from San Diego (with Sherrill Milnes as the king) and from Montpellier (with Alain Fondary in that role).

The new recording captures a single unstaged performance in September 2019. It displays Saint-Saëns’s mastery as a theater composer again and again, a point reinforced by the various passages that we are now hearing for the first time.

Ellie Dehn and Erin Merceruio Nelson with the orchestra in Odyssey Opera’s 2019 performance of Henry VIII. Photo: Kathy Wittman

Saint-Saëns and his librettists developed the libretto from elements in two plays: Calderón’s Spanish drama The Schism in England (c. 1627) and Shakespeare’s aforementioned Henry VIII (1613; possibly co-authored, or touched up, by John Fletcher). Notable operas by composers a generation or two earlier (Rossini, Donizetti, and Ambroise Thomas) had already featured appearances by Henry VIII’s second and third wives, Anne Boleyn and Jane Seymour (in Donizetti’s Anna Bolena), and his daughter and successor, Elizabeth I. Saint-Saëns took the chance of portraying on stage the single most momentous turn in Henry’s tempestuous life (and one of the most consequential decisions in world history): Anne Boleyn’s arrival at the court, the king’s insistence on divorcing Catherine of Aragon and marrying Anne, and his declaring himself the head of the Church of England and therefore not subject to the authority of the Pope in Rome.

Contemporary critics were perennially doubtful about Saint-Saëns’s ability to create viable operas, in part because his orchestral, chamber, and solo-piano works were so highly regarded. (Did they not remember that Mozart, for one, was equally superb in opera and in instrumental genres?) They also tended to imply that he was merely copying Wagner if he did something as simple as make hefty use of the brass or bring back in altered form a theme heard in an earlier act. But Henry VIII was a success, thanks in part to some major cuts. It was revived at the Opéra frequently during the composer’s lifetime and got picked up by theaters in dozens of cities, including Milan (La Scala, in Italian), Moscow (in Russian), and Cairo (in French).

Like all of his operas except Samson et Dalila, the work went into eclipse for over half a century and is rarely staged nowadays. Most importantly, the new recording restores, for the first time, the massive cuts made before the work’s premiere and in subsequent stagings. These include a magnificent septet at the end of Act 2 and a major scene early in Act 3.

The three most extensive roles are those of Henry VIII (baritone), Queen Catherine (soprano), and Anne Boleyn (mezzo). The vocal categories for the latter two are very significant, because they coincide with characterization, reinforcing Catherine’s virtuousness and rectitude and Anne’s sensuality and deviousness.

We enter the opera at the moment when the king is about to introduce Anne to the court as a lady-in-waiting to the queen. The libretto gives Anne a lover, Don Gomez, who has followed her to England; she, however, schemes to become queen in place of Catherine. Gomez has entrusted to Catherine (a fellow Spaniard) a letter from Anne, written some time earlier, admitting her love for Gomez.

Hilary Ginther in Odyssey Opera’s 2019 performance of Henry VIII. Photo: Kathy Wittman

Henry plays a nasty game with his wife, assuring her, at first, that Anne is just a lovely new friend for her. But he eventually reveals his plan, arguing that his marriage to Catherine is invalid because she was previously married to his late brother. He builds his case, quite dubiously, on the book of Leviticus.

Henry announces a split between England and Rome, and he imprisons Catherine (comfortably, one assumes) in a country castle. Still, the possibility that Anne loves Gomez haunts him. The opera ends with his trying to persuade Catherine to hand him the incriminating letter. She tosses it into the fire and dies, presumably of heartbreak, Henry glares threateningly at Anne and sings of the ax that awaits anybody who brooks his will, and the curtain (though not yet the ax) falls.

This plot — I’ve left out some interesting complications — allows for character-defining arias (four of them have been previously recorded on one or another aria disc, e.g., by Elīna Garanča or Boris Christoff) and fiery duets, including two splendid faceoffs between Anne and Catherine (before Anne becomes queen and after Catherine has been cast off).

There are also many beautifully written moments for the chorus, each of them appropriate to its specific place in the plot, plus a choral/orchestral funeral march as the Duke of Buckingham is led to the scaffold despite pleas from Catherine that the man is innocent.

A colorful and wildly varied eight-number divertissement at the end of Act 2 includes a “Danse de la Gipsy” — the one number from the entire opera that managed to get performed regularly (as an isolated orchestral number) throughout the 20th century. (I learned it from a Boston Pops LP that also contained Dukas’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.) I should mention that Saint-Saëns flipped through some early British music collections to find tunes that would give the score some appropriate local color. I was surprised, for example, to hear “The Miller of Dee,” a sprightly song I knew from Beethoven’s arrangement of it. (There’s a Deutsche Grammophon recording of it by a group of singers including Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, all hopelessly struggling with English pronunciation.)

The music shows the mastery of phrase structure, melodic variety, harmonic subtlety, and orchestral figuration and color that we know from Samson (composed two decades earlier) and from Saint-Saëns’s marvelous symphonies and symphonic poems. Each scene and confrontation is trenchantly characterized, and the Act 2 septet certainly deserves to be reinserted into the opera, if there are (as I hope there will be) staged productions in coming years.

The forces of Odyssey Opera are under Rose’s usual alert control, and each of the soloists is highly accomplished and (with one exception) pronounces French well. The recorded sound captures everything clearly and in comfortable balance — a remarkable feat that one normally finds only in studio recordings.

Ellie Dehn repeats her magnificent reading (from the Botstein recording) of the central role of the ill-used queen, and of course gets some new passages to sing as well. Michael Chioldi sings grandly — or sometimes in a meaningful murmur — as Henry VIII. Hilary Ginther, the scheming Anne, reveals what the reviewer in the Boston Musical Intelligencer rightly described as a “darkly projected voice” and “melting lyricism.”

The numerous secondary roles are handled with intelligence and vocal steadiness by such singers as Matthew DiBattista, David Kravitz, and Kevin Deas. The one oddity in the casting is the Armenian tenor Yeghishe Manucharyan as the Spanish ambassador Don Gomez who is hopelessly in love with Anne. His singing — he got his training in Moscow, Yerevan, and, finally, Boston — is sweet, grand, and beautifully tuned. But his French is utterly Italianate — with hardly a single nasal vowel. I kept wondering if Manrico had wandered in from Verdi’s Il trovatore. Was the idea that an Italian accent can substitute for a Spanish one? But it doesn’t. And, in any case, opera is hardly a realistic medium in quite that way! I look forward to hearing Manucharyan again, in operas where he can pronounce the language in an undistracting manner.

The booklet contains an excellent essay by Hugh Macdonald. For much more detail on the work’s origins, musicodramatic coherence, and performance history, consult his recent magisterial book Saint-Saëns and the Stage.

Ellie Dehn in Odyssey Opera’s 2019 performance of Henry VIII. Photo: Kathy Wittman

The libretto is provided, but in a nearly word-for-word translation (uncredited) that often misses the point or doesn’t even seem to be trying to figure it out. The original French libretto regularly relies on pseudo-archaic inverted word order. This feature should have been straightened out in translation. Also, some structures and words are outright mistranslated. “Le ciel vous garde son amour!” is not, in context, “Heaven keeps her love for you” (the translator treats the verb as a simple present tense) but a kindly wish, in the subjunctive: “May Heaven protect her love for you!” or, to use more explicit words, “May you, if it be God’s will, find that she still loves you [even though you two have been separated from each other for a time]!”

And here’s another typically incomprehensible string of English words: “From what front is the infamous going to approach me?” The French text here uses front in its normal sense of “forehead” but means it metaphorically. The sense is thus: “What sort of attitude/greeting can I expect to encounter when I meet the faithless one?”

I am astounded, as I was with a previous Odyssey Opera release (Gounod’s La reine de Saba), that an organization in Boston — my dear hometown, renowned as a center of higher learning — did not care enough to find someone who could render French into clear English.

I should add, further, that some chunks of the libretto are missing entirely. Worse, these all seem to be for passages that have been restored (in other words, they are not to be found in most previously available printed scores). For example, after Anne’s wonderful soliloquy “Reine! Je serai reine!” Don Gomez enters and has a significant scene with her and then, apparently, leaves (I’m guessing). The printed libretto simply jumps to Catherine’s entrance and first confrontation with Anne.

Despite this, the four-CD set is a must-purchase for French-opera lovers. In 2019, Macdonald wrote, “Of all Saint-Saëns’s operas, the urgent need of a good, complete recording of Henry VIII is the most glaring.” That need has now been met. (I’ve written to Odyssey Opera, recommending that they put a full, corrected version of the libretto up on their website. No response yet. But don’t let that stop you from buying the fine recording!)

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here by kind permission.

I must admit that I have fallen in love with Henry VIII; what a terrific opera it is! It certainly deserves to be done more often, and with all the cuts restored and a good ballet. I know it’s long, that way; but it really is so beautifully written and makes so much better sense, that way. My first introduction to this opera was in an extremely cut version, and I did not get the point of the story. Now, with the whole thing intact, I can appreciate what wonderful balance and character studies it presents.