Film Review: “Armageddon Time” — Falling Between Two Worlds

By Steve Erickson

In James Gray’s new film, the tragedy and pain behind Jewish assimilation lurks just out of frame.

Armageddon Time, directed by James Gray. Screening at the Brattle Theatre, part of IFFB Fall Focus, on October 29.

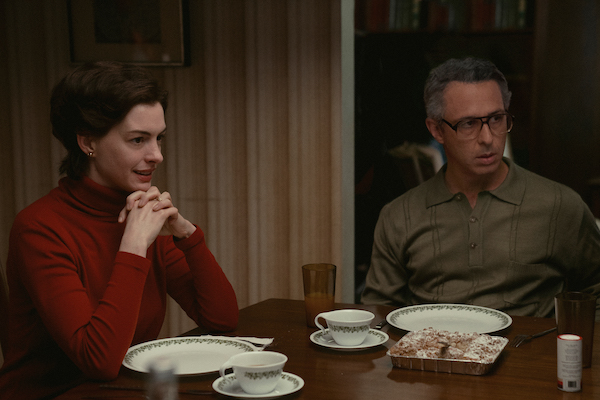

Anne Hathaway and Jeremy Strong in a scene from Armageddon Time. Photo: Anne Joyce/Focus Features

Armageddon Time is a film about its own inadequacies. Set just before Ronald Reagan’s 1980 election, it’s full of markers of an America whose worst tendencies, despite superficial changes, persist. In the press kit, director James Gray states that “the American Dream always figured prominently in the story my family liked to tell about itself. We didn’t buy many of the empty bromides, but we believed wholeheartedly in the arc of the greater narrative.… Our privilege was both real and fraught.”

As generational tides pass to the tune of the Clash (whose cover of reggae singer Willie Williams’s song supplies the film’s title) and Sugarhill Gang, the tragedy and pain behind Jewish assimilation lurks just out of frame. Paul (Banks Pereta) is a boy growing up in a middle-class Jewish family in Queens, surrounded by a history of racism and antisemitism he doesn’t understand. It’s James Gray’s most autobiographical film, drawing its entire plot from his own experiences around that time.

Paul enters the sixth grade, hanging out with his Black friend Johnny (Jaylin Webb). Their teacher dislikes both, but singles Johnny out for insults. Inspired by a museum trip, Paul decides he wants to become a painter. Paul and Johnny are perceived as troublemakers, but this only has real consequences for Paul when Johnny hands him a joint in the bathroom and suggests they smoke it in a stall. Paul doesn’t seem to know what it is, but they get high together. Unfortunately, their teacher notices the smell and the sound of the boys giggling. After Paul gets caught, his parents — Irving (Jeremy Strong), a plumber, and Esther (Anne Hathaway) — force him into attending a private school. He remains friends with Johnny, whose life grows more difficult, for reasons that Paul doesn’t really comprehend. He’s close to his grandfather Aaron (Anthony Hopkins). But Paul is willing to let Johnny stay in a small house on the family’s property when Johnny’s grandmother’s health problems become too much to bear.

Darius Khondji’s cinematography paints the film in earth tones, fitting a movie set during the fall. The visuals have the nostalgic look of a book of faded photographs. However, the narrative doesn’t romanticize the past. The roots of the far right’s present rise are everywhere, from Reagan’s remarks in a TV interview about America turning into Sodom and Gomorrah to Paul’s attendance at an academy frequented by Fred Trump. If that last detail, down to a speech from Mary-Ann Trump celebrating her success as a lawyer, weren’t taken straight from Gray’s life, it could be dismissed as too heavy-handed.

Banks Repeta and Anthony Hopkins in a scene from Armageddon Time.

Much of Gray’s work has been based around the Jewish neighborhoods in New York City where he grew up. At first, he told these stories through a neo-noir lens. Although he began working in the ’90s, his early films lacked the ironic touch of other genre work by directors of his generation. While they drew upon film references, it was not jokey pop culture references and hip distance. They tended to treat petty criminals in Brooklyn with the grandeur of Coppola’s gangsters. Gray might have felt at home back in New Hollywood, but he struggled to find a wide audience in the US decades later. (At first, his critical support came mostly from France.) Starting with Two Lovers, his films abandoned their genre elements — The Immigrant and The Lost City of Z turned to the past. Made with the biggest budget of his career, Ad Astra turned to the future, but, while it was stylistically spectacular, its intimate musing on troubled father-son relationships did not benefit from the sci-fi trappings and solar system-spanning scope. Gray has recently admitted his control over the film was taken away during the editing.

Clearly, Gray’s films have usually drawn on elements of his own life, even when they are not explicitly autobiographical (The Immigrant was based on his grandparents’ experiences in the US in the ’20s Armageddon Time takes this memoir approach to a new extreme. Paul’s family is well sketched-in. Critic Owen Gleiberman’s comparison to Barry Levinson’s multigenerational Jewish-American saga Avalon is on target. Hopkins, Strong, and Hathaway breathe considerable life into their roles. While Irving is not sympathetic, especially after he hits Paul, his face suggests his struggle to enter the middle class and the anger he’s had to hide to stay there. Irving and Esther don’t understand some elemental contradictions: they talk about the impact of the Holocaust on their family (something Paul doesn’t fully comprehend till Aaron describes his mother’s expulsion from Ukraine), but then indulge in casual racism toward Blacks and Asians the next moment.

Ironically, the film’s inability to do justice to Johnny is the film’s biggest problem. The scenes with Paul and his relatives show a believable dynamic that is absent from the two boys’ friendship. Armageddon Time sees Johnny just as Paul does. But, as an adult filmmaker, Gray should be capable of greater curiosity and outreach than his young stand-in. The ellipses in Johnny’s own story — an event at a Sugarhill Gang concert that apparently led to an injured foot, an unseen grandmother who becomes impossible to live with — push him away from the center of Armageddon Time. Another film could be made about his life.

This imbalance becomes particularly problematic in the final half hour of the film. Without giving away spoilers, Paul makes a decision that has grave consequences for Johnny, who makes choices that benefit Paul, who walks away drenched in sadness. Gray does not come close to doing justice to the gravity of the situation. He, like many white directors, falls into a common trap. Armageddon Time embraces liberal guilt and shame but supplies no ideas about what to do with them — beyond confessing that they are there. Here, the demand for diverse stories and authentic ones, based on personal experience, ends up undercutting both.

Steve Erickson writes about film and music for Gay City News, Slant Magazine, the Nashville Scene, Trouser Press, and other outlets. He also produces electronic music under the tag callinamagician. His latest album, The Bloodshot Eye of Horus, was released in November 2022, and is available to stream here.

Tagged: Anne Hathaway, Anthony Hopkins, Armageddon Time, James Gray, Jeremy Strong