Visual Arts Review: “Life Magazine and the Power of Photography” — Some Fake Views?

By Charles Giuliano

While impressive, Life Magazine and the Power of Photography disappoints.

Robert Capa, Normandy Invasion on D-Day, Soldier Advancing Through Surf, 1944.Robert Capa © International Center of Photography / Magnum Photos. Photo courtesy Museum of Fine Arts

Through January 16, 2023, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts is presenting Life Magazine and the Power of Photography. The exhibition brings together more than 180 objects, including original press prints, contact sheets, shooting scripts, internal memos, and layout experiments. The show is a collaboration between the MFA and the Princeton University Art Museum. It has been curated by MFA’s Kristen Gresh, Princeton’s Katherine A. Bussard, and independent curator Alissa Schapiro, and draws on unprecedented access to Life’s picture and paper archives.

While impressive, the project disappoints. The museum’s intent was to generate “critical reflections on how photojournalism and the politics of images frame urgent conversations about implicit biases and systemic racism in contemporary media.” This mission is contradicted by curatorial non sequitur: too much precious space is given to works by contemporary artists Alexandra Bell, Alfredo Jaar, and Julia Wachtel.

A Robert Capra contact sheet. Photo by Charles Giuliano

The curators had access to the finest images snapped by the greatest photojournalists of their generation, most of whom worked for publisher Henry Luce, who bought Life in 1936, primarily for its title. At the time he also owned Time (1923), Fortune (1929), and Sports Illustrated (1954).

Among the over 30 photographers featured in Life Magazine and the Power of Photography are Margaret Bourke-White, Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Frank Dandridge, Alfred Eisenstaedt, Carl Mydans, Charles Moore, Gordon Parks, and W. Eugene Smith. If more space had been given to exhibit their work — rather than meet the requirements of social justice self-gratification — this might have been a definitive exhibition of documentary photography.

That benchmark remains The Family of Man (January 24-May 8, 1955), an exhibition of 503 photographs from 68 countries curated by Edward Steichen, the director of the New York City Museum of Modern Art’s (MoMA) Department of Photography. The show traveled for eight years.

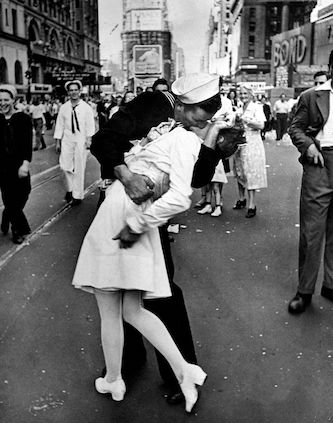

Alfred Eisenstaedt, VJ Day in Times Square, 1945. Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt. © LIFE Picture Collection. Photo courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts

During the ’40s I came of age, and pictorial awareness of WWII, through Life and the Movietone News. They conveyed the graphic images of conflict before television made Vietnam the first “living room war.” On VJ Day Eisendtadt captured what Cartier-Bresson dubbed “the decisive moment.” Culled from the thousands of individual frames, this depiction of a sailor kissing a nurse became an iconic image.

Life’s combat coverage continued with Korea (“The Forgotten War”) and ended with Vietnam. The exhibition includes the only published photo media coverage of D-Day; Robert Capa’s Normandy Invasion on D‐Day, Soldier Advancing Through Surf. However, this singular image begs many questions. The maneuvering around the picture underscores how photographers and editors were willing to manipulate and falsify information to sell newspapers, magazines, and media catnip. Capa claimed to have taken 106 images, but only The Magnificent Eleven survived. The exhibition includes the contract sheet. One version of the story claims that an inexperienced technician botched the development of the photos. Others argue that Capa only took 11 frames — he was only on the beach briefly. The alleged “combat” shots were really of Army engineers dismantling enemy defenses. Skeptics charge that Capa rushed back to make his deadline with what little he had.

The images ran in Life magazine’s issue on June 19, 1944, with captions written by magazine staffers. Capa did not supply Life with any notes or verbal descriptions of what they showed. These captions and his later descriptions have proven to be erroneous.

This was not Capa’s only controversy. That started with his 1936 photograph Death of a Militiaman, the most iconic image from the Spanish Civil War. Doubts began in the ’70s. Ernest Alos, a reporter for Catalonia’s daily El Periodico, led the latest inquiry: “We discovered that the picture does not correspond to any actual event.”

On the subject of “fake news,” there are instances of falsified or exaggerated reporting as well as repressed news. The My Lai Massacre in Vietnam was eventually reported — after Seymour Hersh pitched it to Life, Look, and major news outlets, who turned it down. In frustration, Hersh went to the small, Washington-based Dispatch News Service, which sent it to 50 major American newspapers — 30 accepted it for publication. Between 347 and 504 unarmed people were killed by American soldiers. Victims included men, women, children, and infants. Some of the women were gang-raped and their bodies mutilated. Some of the dead were as young as 12. Twenty-six soldiers were charged with criminal offenses, but only Lieutenant William Calley Jr., a platoon leader in C Company, was convicted. Found guilty of murdering 22 villagers, he was originally given a life sentence. He ended up serving three-and-a-half years under house arrest after President Richard Nixon commuted his sentence.

As for falsifying combat photojournalism, the practice started with the American Civil War. Mathew B. Brady (c. 1822-24–1896) operated a successful photo portrait studio in New York creating daguerreotypes. After the Civil War started, he created thousands of war scenes, as well as taking admiring portraits of Union generals and politicians. Most of the photos were taken by assistants, who included Alexander Gardner, James Gardner, Timothy H. O’Sullivan, William Pywell, George N. Barnard, Thomas C. Roche, and 17 other men.

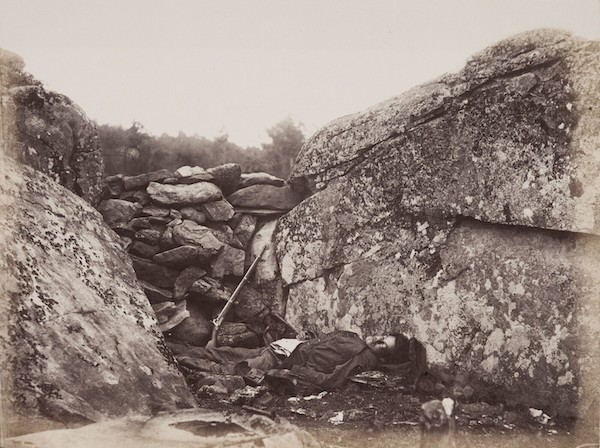

Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg, 1863. Print 1866 by Alexander Gardner.

A representative image is Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg, 1863. In it, we see the corpse of a Confederate soldier — the body was posed to create a phony narrative. The long exposures of the day’s cumbersome cameras precluded taking any action shots. That didn’t stop Brady, who in October 1862 opened an exhibition in his New York gallery titled The Dead of Antietam.

Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima is a famous photograph of six United States Marines raising the US flag atop Mount Suribachi. Shot by Joe Rosenthal of the Associated Press on February 23, 1945, it was, in fact, the second of two takes. Rosenthal missed when the United States Marines first raised the American flag. The Associated Press photographer was still climbing up the mountain at the time. Marine Staff Sgt. Louis Lowery of Leatherneck Magazine was there to capture the first raising. His camera was broken after he dived for cover. The initial flag was too small, so the Marines raised a larger one, which is what Rosenthal captured. There were arguments then (and now) that he staged the celebrated shot.

The men pictured in the photograph are Harlon Block, Harold Keller, Ira Hayes, Harold Schultz, Franklin Sousley and Michael Strank. Several of them were removed from combat and sent on tour back home to sell war bonds.

Although Carl Mydans photographed some of the Leyte campaign, he missed General MacArthur’s famous return to the Philippines. On January 9, 1945, Mydans photographed MacArthur as he landed in Luzon. Photo courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts

While it is not clear if Rosenthal staged his heralded image, Life photographer Carl Mydans most certainly did. He covered General Douglas MacArthur, who was a bloodhound for publicity. He aspired to be President until Harry Truman relieved him of his command in Korea. Forced to abandon the Philippines, MacArthur vowed “I shall return.” Mydans missed the return to Leyte, but shot his Luzon landing, in which MacArthur and staff waded ashore.

The bottom line when it came to the “power of photography”: Luce and Life were not above bending the truth because of naked self-interest or for the sake of boosting America’s image.

Charles Giuliano has published his seventh book, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: 1970 to 2020 an Oral History. He publishes and edits Berkshire Fine Arts.

Tagged: Charles Giuliano, Life Magazine, museum-of-fine-arts-boston