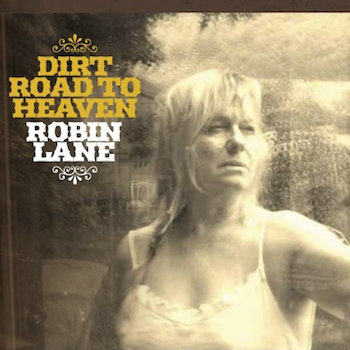

Music Interview: Singer Songwriter Robin Lane on a “Dirt Road to Heaven”

By Tim Jackson

Singer and songwriter Robin Lane talks about the genesis of her new album. She will be performing live around New England with a new ensemble.

Singer and songwriter Robin Lane began her musical career singing with Neil Young on the Everybody Knows This is Nowhere album. She then went on to form the renowned band Robin Lane & The Chartbusters in 1979, whose hit single “When Things Go Wrong” was the eleventh video broadcast on the debut day of MTV.

This writer, who was an original member of the group, directed a film about her life called When Things Go Wrong in 2013. It featured her work with Songbird Sings, a nonprofit creative songwriting collaborative that she began in 2010 to help women survivors of violence and abuse. Those songs resulted in 10 short Woman’s Voice CDs.

In 2019 Many Years Ago: The Complete Robin Lane & The Chartbusters Collection, a three set CD of remastered tapes and demos, was released.

Robin’s latest solo CD of all new songs is called Dirt Road to Heaven on Red on Red Records. She is again performing live around New England with a new ensemble.

I sat with Robin to discuss her songwriting and the genesis of the CD.

Arts Fuse: What is the genesis of this new CD Dirt Road to Heaven?

Robin Lane: I never really decided to do a new recording. It was totally organic. When we were in Marblehead recording a song for your 2016 movie (When Things Go Wrong: Robin Lane’s Story) we put down the song, “False Memory Syndrome,” with a group of fabulous women at Ringo Studios in Marblehead, which is John Pfister’s studio. He is also a bass player. It started there. Then I had to go to California for two years for personal reasons. And, of course, there was Covid during which I recorded in pieces.

AF: Are these new songs?

RL: I don’t think most are. I started out wanting to do a country album. I had country songs and I was playing around with them in his studio. Then I suddenly remembered my song “Dirt Road to Heaven,” which is now the title song of this album. Then these other songs started popping up that I recalled writing.

AF: Would these songs have been appropriate for a band sound?

RL: I don’t think they are, no, but these were all songs from my own repertoire. In the last decade I made 10 CDs of about 6 songs each that came from workshops called “A Woman’s Voice.” These were collaborative songwriting workshops for women who had survived domestic abuse, violence, trauma, drug addiction, who were in prisons and so forth. They’d write lyrics and I’d ask what kind of song they want? That’s what “False Memory Syndrome” was, a powerful memory song, which we composed in a session that was filmed for the film. But it wasn’t right for the tone of this collection. Many of those songs were not right for this project.

AF: Did the workshops impact your own writing?

Robin Lane. Photo: Tim Jackson.

RL: Probably it built confidence in myself and my songwriting. I don’t think with the Chartbusters that I thought about songwriting really that much. Plus the band would help with the music. But John Pfister is really good with helping me piece together ideas and sounds. I would play bass parts and then give them to him to play and record. There were also handmade instruments to experiment with — like this guitar that has all these different sounds. I’d play something that I never thought I’d play or do the same on a piano or some new instrument. I was sort of producing music as I went along. Of course, John was the actual producer, but the process gave me the freedom to play around and to discover things.

AF: So this was a freer way to work then when you were writing for a band sound?

RL: Oh, yeah. Very free and creative. Musically I did exactly what I wanted to do on these songs. Lyrically, too, though some of these songs are kind of weird.

AF: Do any of the songs reflect on being older as a woman and as an artist and songwriter?

RL: Not really. The songs “Dirt Road to Heaven” and “A Woman Like That” are pretty powerful. But I’m not really making statements other than I’m walking in my own direction. Actually, the former tune is kind of about the end of the world.

AF: That’s uplifting! Does that mean we’re going to hell in a handbasket?

RL: That’s actually another song. If there’s a heaven, like an actual place, we’re already in it. It’s the source we came from. It’s everything. We’re making our heaven or hell as we go along. When we die we become just more of the energy from the place we came from in the first place.

AF: A cosmic continuum, of sorts.

RL: Yeah.

AF: Many people didn’t know that you were Christian during the Chartbuster years.

RL: Some did and some didn’t. I don’t remember talking about it much. But I recall Larry Mullin of U-2 saying I talked about it too much. That band began as Christian but it never talked about it much. It is how I initially became friends with them, but I don’t remember talking about my Christianity a lot. There were some articles in Christian magazines. Maybe that’s what he saw.

AF: But your songwriting was informed by belief. You were not writing to a “man,” you were writing to a ‘higher power.’ God, if you will.

RL: Yeah. I’ve written a lot of songs that are to myself, not some man. Back in those days, in a song like “Are You My Hero Now,” I was talking about Jesus. I would talk about him in songs all the time or “I Don’t Wanna Know” (a punk song about Sid Vicious’s killing of Nancy Spungen). Despite knowing that he killed her, I still believed Jesus would have loved them. It does say –“Jesus you better come back quick ‘cause you know I’ve had enough.” And words like:

I know I could love him.

I know I really could.

Because there’s no here among us now

Who is living up to be good.

I don’t wanna know (don’t ask why)

I don’t wanna know (did she cry)

I don’t wanna know (the night she died)

AF: Did any of that belief cross into this CD?

RL: Some were written earlier and some later. There is a CD that I did back in the ’90s called, Catbird’s Seat (produced by her ex-husband Ducky Carlisle) and a late Chartbusters CD in the 2000’s called Piece of Mind (produced by David Minehan at Wooly Mammoth). In the years since, I wanted to keep recording but I had no way of doing it. It costs money. Thank goodness for my bass player, John Pfister who owns Ringo Studios. He was willing to collaborate.

AF: Do critics often assume that your songs need to be interpreted as feminist or that they are speaking about the experience of aging?

RL: Yeah, actually. There are always questions about being a woman and getting power and so forth. Maybe because the music has been labeled ‘Americana’ and it comes with the genre, I don’t know. It’s all music that is just being real — no need to attach a label or issue. It’s about honesty. Speaking from the heart. The assumption is that I’m speaking for all women when really I’m just writing a song.

I remember back in the day when rock critics really held sway, I would think ‘wait a minute, these are just songs.’ But the writers would be the ones to “figure out” what a song was all about, its deeper meaning. Again, the song “I Don’t Wanna Know”– I think it was Greil Marcus who said that it was the greatest feminist rock anthem he’d ever heard. Maybe one doesn’t always intend things. Or perhaps some do. Mainly, you just write.

Robin Lane and Tim Jackson performing with the Chartbusters.

AF: You say the album has a vibe. What do you mean?

RL: There is a DJ in South Carolina who was playing the album and going over the songs and he said by the 5th or 6th song, “Hurricane Watch,” that he was hit with the same feeling he’d had when he was younger listening to Carole King’s albums and Joni Mitchell. He felt there was a vibe and a continuity to the album. There is, but I don’t really know what that is exactly. The songs just go together, helped by not having any time constraint – getting to do a guitar part like twenty times. And then keeping all the takes.

One thing Pfister is especially good at is sorting through all these tracks, a process that would make most anybody nuts. He listens, he picks. He mixes and matches. This 20th guitar part would be good here, but also it might work well in the 3d verse, and so forth.

AF: The benefit of Pro Tools as a music editing program. It allows him to create a kind of . . .

RL: Puzzle. It’s a puzzle. Moving things around. Like David Bowie, who would put things where they’re not supposed to go. A mistake isn’t a mistake. It becomes part of a new whole.

AF: For you this is a new way to create a song.

RL: Yeah. That’s why there are all these musical people out there creating on their computers. A lot of stuff in the ’90s passed me by. Like Massive Attack. Have you heard of them? Music coming out of England at the time was much different than traditional pop or anything. Atmospheric. It’s how Pfister plays with analog and digital. Even though Neil Young thinks digital makes music colder, this album is not cold. It records analog and arranges digitally. There are real instruments, real instruments always. It allows me to play around and create.

AF: There are also other musicians involved, I assume.

RL: Oh yeah, there’s Milt Reder from 4 Piece Suit and a producer himself, John Sands who plays with Aimee Mann and many others, Russell Chudnowsky who has worked with Tanya Donnelly, and EJ Ouelette. You are on the record, as is Asa Brebner. And there are also songs in collaboration with William Fuqua, who used to manage many bands like Crazy Horse and Tom Petty, and your wife, Suzanne Boucher. With Danny Hillis, an American inventor and an old friend, we co-wrote a song called “No Fear.” There is even a song by the late Asa Brebner.

Robin Lane — “when you create maybe that’s when you make sense of the nonsensical.”

AF: Who do you listen to for inspiration?

RL: I think Brandi Carlile is awesome. And PJ Harvey. She’s like the David Bowie of females. Now there’s someone you can take a lot from. And she’s really sexy. But I never consciously borrow. If something is really obscure, something I’ve never heard before, I might think that I want to write a song like that. But I don’t copy it per se.

While I was doing this album, I tried to record with some other guys like Ray Mason but it wasn’t working for me so well. So right in the middle of this recording, which I initially intended as a country album, I started writing a whole bunch of new songs. So now I have a whole other album ready to record. So that’s fun. But they are weirder songs, hardly about Jesus or anything, more like about outer space or something. Or, why do we have two eyes? What’s the reason we’re alive? Strange, fun, anything I want to say. They don’t have to make sense. I don’t make sense in my life so how can I, well . . . when you create maybe that’s when you make sense of the nonsensical.

AF: It’s how you give your life a sense of order?

RL: There you go.

Robin Lane’s new CD, Dirt Road to Heaven, is released by Red on Red Records and is available at the therobinlane.com or at https://redonredrecords.bandcamp.com/ and all digital platforms.

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story, and the short film The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.

Tagged: Dirt Road to Heaven, Red on Red Records, Robin Lane, Robin Lane & The Chartbusters