Book Review: “Dinners With Ruth” — Always Nice But Rarely Incisive

By Helen Epstein

Like a Hallmark movie, Dinners with Ruth is an engaging and entertaining story, with episodes of great pathos. It is an upbeat, easy-to-read gift book, which is what the publisher intended.

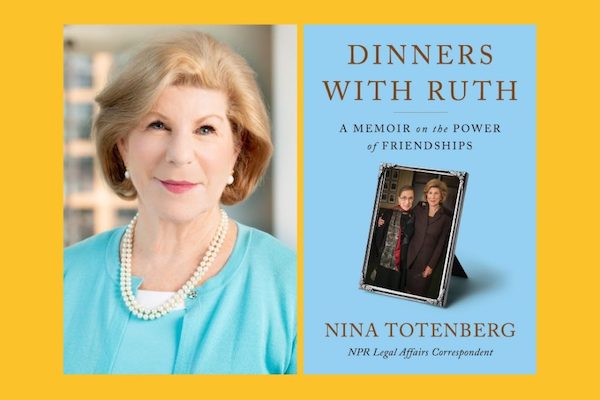

Dinners With Ruth: A Memoir on the Power of Friendships by Nina Totenberg. Simon & Schuster, 320 pages, $27.99.

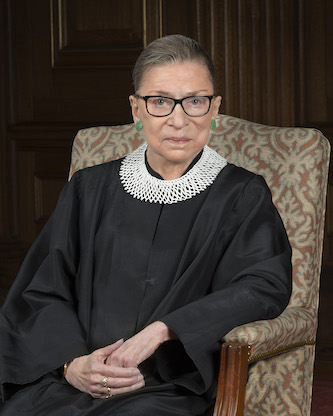

I was highly predisposed to enjoy this memoir and I did — mostly. As a longtime listener to public radio, I always welcome hearing NPR Legal Affairs Correspondent Nina Totenberg’s voice as well as her elucidation of the activities of the Supreme Court. Also, I read anything I can about the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, an extraordinary figure who kept working (and working out) through three bouts of cancer and other illnesses, even participating in Supreme Court oral arguments from her hospital bed. I also love stories of long friendships and anticipated lots of intimate anecdotes as well as details about Totenberg herself: what kind of family she came from, how she got into legal journalism without studying law or even finishing college, who helped her and who got in her way.

I expected Dinners with Ruth to be something like Tuesdays with Morrie, Mitch Albom’s bestselling memoir of intimate conversations with his mentor, Brandeis sociology professor Morris Schwartz. The dinners with Justice Ginsburg and her husband Martin begin late in the book; most of the volume is autobiographical, serving up interesting glimpses of the Ginsburgs and mini-profiles of other figures in establishment Washington, DC. Some key sections are moving; others are entertaining. But that selection left me wondering what Totenberg — consciously or not — left out.

The author was born in January of 1944, putting her on the prefeminist side of the great cultural divide of the 1960s, before women found safety in numbers in the professional world when, as she puts it, they “gently fended off unwanted advances,” quietly and one by one. She and her “radio sisters” Linda Wertheimer and Cokie Roberts (there is barely a mention of Susan Stamberg) were more buttoned-up, and less able to recognize and report sexual harassment than women who entered journalism just a few years later.

Her tone, her anecdotes, and mini-profiles of prominent DC personalities are in ’50s good taste. She takes pride in her appearance and entertaining at home. She all but apologizes for calling Senator Alan Simpson a “fucking bully” when, after a televised debate about the Clarence Thomas nomination to the Supreme Court, he becomes so angry that he intercepts her ride home so he can continue his rant. (Her driver comments that she should get herself a gun, but she finds a way to, as she quaintly puts it, “become friends.”) Mixed in with her ladylike manners is a weird casualness about professional boundaries that runs through her 50 years of reporting. And it is that that makes me uneasy.

As I read, I also kept reflecting that journalists have a handicap when writing a memoir: trained to observe, listen to, and analyze other people, they are unaccustomed to observing and analyzing themselves. They need editors to point out their blind spots, and careful editing is scarce in today’s bottom-line publishing environment. Dinners with Ruth suffers from it.

A careful editor would have asked Totenberg to explain more fully her casual approach to professional boundaries, for her to specify dates and places and to clarify context. A professional would have noted gaps and bumps in a narrative that seems to have been compiled from a series of interviews and speeches. The book’s tone is perky and conversational, much like Totenberg’s reports on the Supreme Court, and it reads like a set of performance pieces. In her acknowledgments, Totenberg gives somewhat vague credit to Lyric Winik, described by the New York Times as “the go-to scribe for political memoirs.” Winik, I infer, structured the source material into a brisk story line that moves chronologically, alternating between sections about Totenberg and sections on Ginsburg.

NPR journalist Nina Totenberg. Photo: Wiki Common

In the all-too-brief family origins section, Totenberg introduces herself as one of three daughters of Roman and Melanie Totenberg. He is a Polish-born virtuoso violinist and longtime Boston University music professor who emigrated to the US before the Holocaust (in which several members of the family were murdered); she is an “independent-minded gorgeous woman” turned realtor whose family name — astonishingly — does not appear anywhere in the book. Although Totenberg’s two younger sisters are named and identified by profession, we don’t learn much about them either, or when and where Nina was born, where she grew up, where she went to school (Wikipedia cites Scarsdale, New York), who her friends were, when she moved to Boston, or what she thought of journalists before she became one.

Nina’s life seems to take off in 1961 when, as “a mere 17-year-old” high school student, her mother arranged an internship for her with the Democratic Study Group, a DC research organization. “Very quickly, I knew for sure that I wanted to be a reporter.” She says, “I was much more interested in watching what went on and telling people about it than I was in fighting for any cause.” Totenberg finished high school and attended Boston University for three years, then dropped out. There’s not much about that period either. Her first job was at Boston’s Record-American, “which several mergers and years later would become today’s Boston Herald. My spot was the women’s page and there’s no polite way to say it: it was a terrible job.”

Her first major story (in 1971 at age 27) was a profile of J. Edgar Hoover for the National Observer, a weekly about which she says little. The piece she writes about the FBI director is well observed and well reported — so well reported that Hoover demanded that the Observer fire her. Instead, the editor defended her. Without any prior legal background, she began covering the Supreme Court. Then, unexpectedly, Totenberg was fired for plagiarism. She had not attributed quotes she had lifted from reporters at the Washington Post, a practice she claimed was usual at the time. As a journalism student in the ’70s, I recall that practice was in fact pilloried. She acknowledges that today it would have ended her career and that it was used against her later by adversaries.

Totenberg was at first usually the only “girl” in a roomful of men. The memoir goes into the progressive particularity of NPR in hiring more than token women, but says relatively little about the feminist revolution of the time, how it affected her personally, or how it affected journalism and lawsuits against other news outlets. And while she alludes to sexual harassment in those years, she seems to have taken it as a given. Her feminist consciousness was not yet raised and she says little about her actual interactions with men in or outside of the office.

I didn’t understand why, after being fired from the Observer, she became the “Washington bureau” of the start-up magazine New Times, but it was there that she realized that “covering the Court was something I could do that other people weren’t as interested in at the time.” She admits that “I was also in over my head. I knew nothing. I wasn’t a lawyer … but I loved it. Not knowing “shit from Shinola” in some ways made me a better reporter. I had to write things so that regular people, people who weren’t lawyers but who might be interested if I wrote a story well, could understand them.”

Her first contact with Ruth Bader Ginsburg was in 1971. When covering an important Supreme Court case called Reed vs. Reed, she needed a mentor who could explain the issues to her. Totenberg made a cold call to Professor Ruth Bader Ginsburg, then a law professor at Rutgers University. As was dramatized in the feature film On the Basis of Sex, the ACLU had asked Professor Ginsburg to be the lead writer on the brief that argued for equal treatment of men and women. About 11 years older than Totenberg, Ginsburg spent an hour on the phone explaining to her how the Fourteenth Amendment applied to all people, not only African Americans, as Totenberg had understood. She quotes Ginsburg as saying about that beginning, “We have been close friends ever since.”

It is a self-serving line for Totenberg to quote and gracious rather than accurate for Ginsburg. For the next nine years, until President Jimmy Carter brought Ginsburg to Washington, the two women had a mostly intermittent telephone relationship. But both women’s careers would soon take off, blazing trails through two highly public fields. Totenberg was hired by NPR as Legal Affairs correspondent in 1975, appearing with increasing frequency on Morning Edition and All Things Considered. In 1980, Ginsburg was appointed to the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia by President Jimmy Carter and moved to DC, where the two women began to socialize. In 1993, President Clinton nominated her to the Supreme Court of the United States. Their friendship lasted for 50 years, deepened by their mutual support, first during the death of Nina’s husband Floyd Haskell in 1998, then with Marty Ginsburg’s passing in 2010, and then RBG’s illnesses.

Theirs was a friendship that accrued vested interest on both sides. Each woman claimed that she crossed no professional boundaries when Ginsburg became a Justice with Totenberg covering the Supreme Court. Journalism is one of the privileged professions that facilitate making fascinating friendships and Ginsburg was far from the only combination of friend/mentor/source Totenberg cultivated. She was never trained as a journalist and never took seriously one of its basic professional tenets: guard against conflict of interest. Every reporter cultivates sources, but not everyone invites them home — even given the Washington proclivity for dinner parties. Totenberg takes pride in what she unequivocally describes as her “friendships” and implies that in DC it works that way for everyone. “Ruth, Nino [Justice Antonin Scalia], [Solicitor General] Ted Olsen, [Associate Justice] Lewis Powell” are all great pals. It’s tempting in retrospect to look back and say, ‘Oh look at Nina, she made such wonderful friends,’” she writes, as though we readers might be jealous. Instead, readers familiar with journalistic ethics will be skeptical. The only person she describes as resisting her invites is Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. “Perhaps my least successful dinner party with any justice was when I invited O’Connor and her husband to my house not long after she was appointed. I got a good sense of the evening when she walked into my tiny kitchen as I was carving my standard leg of lamb … then said, without preamble, ‘You’re cutting against the grain.’”

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Photo: Wiki Common

Another woman who sensibly kept Totenberg at a distance was Anita Hill, at the start of what Totenberg calls her “biggest story.” President Bush had made the controversial nomination of a then judicially inexperienced and very conservative African American Clarence Thomas to replace retiring progressive and first African American Justice Thurgood Marshall on the Supreme Court. During his hearings, Totenberg writes, then-Senator Biden had made what she heard as unusual remarks about Thomas’s character and “that all the committee members had been given large manila envelopes and they were looking at the contents. The clear subtext was that this involved something that was perhaps highly inappropriate.” She had heard rumors of sexual harassment but had no facts. That pubic hair on the Coca-Cola can was an image not yet on the horizon.

Totenberg’s sources, whose identity she says she will carry to her grave, led her to Hill, then a law professor at the University of Oklahoma, who had once worked for Thomas. When the reporter telephoned, claiming that she was working on a piece about Black law professors, Hill did not buy it. “I know why you’re calling,” and said that she would not talk to the reporter unless she obtained and read a copy of her sworn affidavit to the Judiciary Committee, which Totenberg had not previously known about. But she dug in and the Anita Hill-Clarence Thomas drama, as seen through the NPR journalist’s eyes, was a bombshell that has resonated for years. It’s a testament to Totenberg’s candor — if not perceptiveness — that she writes, “I, who had spent years gently fending off unwanted advances, had not fully realized what a festering wound this was for so many working women. When I reported the story, my first thought was that this was a very important political story. It never occurred to me that it was a sociological story as well, about a phenomenon that had gone largely ignored, and about which there was a volcano of experience and emotion ready to erupt.”

Totenberg’s most moving stories in Dinners with Ruth are about how the two women helped one another through the grave illnesses of their husbands. The reporter’s first husband was the late Senator from Colorado Floyd Haskell, a man 26 years older than herself, who died after they were married for 15 years.

Ginsburg advised the younger woman and helped keep her going. When Ginsburg’s husband became ill, Totenberg and her second husband reciprocated.

During that time, Ginsburg became RBG and Totenberg her interlocutor; the pair performed an ongoing road show at law schools and other venues together. Totenberg is therefore privy to the stages of the Justice’s ongoing illnesses and by 2020, wonders every morning whether Ginsburg (who has had shingles, intestinal blockages, and a return of pancreatic cancer) will die that day or the next. The uneasiness I had felt all along as I read about blurred boundaries between professional and personal relationships became pressing. The informed reader is aware that the reporter has been withholding crucial news about the judge for at least a decade, but Totenberg does not delve into her feelings and reasons for not discussing retirement with Ginsburg and/or suggesting to her editors at NPR that they find another reporter to cover this story. I infer that Ginsburg had seen Justice Sandra Day O’Connor retire at 75 and knew that she regretted the decision. Also, Justice John Paul Stevens stepped down when he was 90, so she saw no reason to leave while she could still work. I learned nothing new about what Totenberg actually thought about the Justice’s retirement. “I chose friendship,” she writes. “It was the best choice I ever made.”

That choice angered many in the legal and journalistic community, and among women whose heroines both women were, including me. Two writers articulated the issues before I could.

Writing in The Hill, Steven Lubet points out that “loyalty to Ginsburg likely kept her from following up on stories that another reporter might have doggedly pursued.” And Totenberg’s front-row seat to the behind-the-scenes drama of Ginsburg’s health became even more complicated after her second husband, David Reines, became one of the Justice’s physicians, adding yet another (legally defined) conflict of interest to the mix.

A scene from the documentary RBG.

Although Totenberg takes pains to describe how she and her husband and she and her friend compartmentalized information and put their loyalty to Ruth above all else, Lubet points out that “Ginsburg’s health was a matter of public concern, and President Obama surely would have wanted to know about it in 2013, when he gently attempted to persuade her to resign…. a reporter without personal relationships to Ginsburg or Reines would have pressed the doctors for details.” Writing in Politico, Michael Schaffer points out that “it would, of course, have required either some persuasion or an act of betrayal. But there’s a chance that a blunt story about Ginsburg’s decline might have changed the trajectory that led to the end of Americans’ right to abortion.”

Given what happened in the wake of Ginsburg’s death, many of us would contest that last point, but Totenberg’s decision (and her own decision not to retire from broadcast journalism at the age of 78) doesn’t make Dinners with Ruth any less interesting. It’s always nice, rarely incisive, and never introspective (I don’t remember any mention of ego or ambition anywhere). Like a Hallmark movie, it’s an engaging and entertaining story, with episodes of great pathos. Dinners with Ruth is an upbeat, easy-to-read gift book, which is undoubtedly what its publisher intended.

Reviewing Dinners with Ruth led me to go back and watch the whimsical but far more informative documentary RBG. It’s not often that I feel that a documentary film has more depth than a nonfiction book, and it is hard for me to critique heartfelt work by a journalistic colleague I generally admire, but, in the end, I found this memoir a little lightweight.

Helen Epstein is a veteran journalist and author. Her latest book is the cancer memoir Getting Through It.

Tagged: Culture Vulture, Dinners with Ruth, Helen Epstein