Book Review: “The Color of Time: Women in History, 1850-1950” — The Past, Colorized

By Kathleen Stone

This coffee table book scan of women’s history reads well and is visually striking.

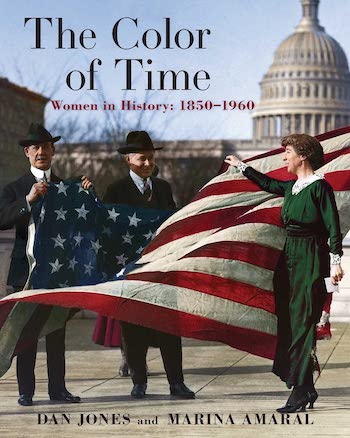

The Color of Time: Women in History, 1850 – 1960 by Dan Jones and Marina Amaral. Pegasus Books, 432 pages, $39.95

In their new book, The Color of Time: Women in History: 1850 – 1960, Dan Jones and Marina Amaral sift through scores of women in history, select close to 200, and bring them to life with newly colored photographs. The result is a glossy compendium that spans just over a century, with intriguing tidbits about the women pictured. Jones and Amaral make a point of including lesser known women, along with the more famous. They also introduce women from various continents who, in some cases, will be new to readers. But the photographs are the book’s most truly distinctive feature. Amaral’s colorized photos create a lush representation of the past that invite, almost seem to pull, the viewer into the frame.

This is not their first collaboration. Using the same format, Jones and Amaral previously published The Color of Time: A New History of the World: 1850-1960 and The World Aflame: A New History of War and Revolution: 1914-1945. Amaral, a Brazilian artist, colorizes old photos while Jones, a British broadcaster, journalist, and author of multiple history books, provides the text. The collaboration has come up with a winning formula. With this installment, they turn their attention to women’s history.

The women in the book are remarkable for what they achieved, no matter their gender, but, considering the constraints, including outright discrimination, that women faced throughout history, they are all the more so. Sunity Devee of India received a citation from Queen Victoria for her work promoting girls’ education in her native country. At that time even high school classes for girls were unusual. Hü King Eng became a doctor in 1894, one of the few women anywhere to work as a doctor in that period. In her home country of China, she performed surgery, ran a hospital and trained students. Vesta Tilley, a cross-dressing singer and dancer, was a sensation in British music halls. Playing drag characters and pantomiming male lead roles, she was the highest-earning woman in Britain during the 1890s. Bess Coleman was a daring airwoman of the ’20s who barnstormed at air shows, circuses and fairs. A Black woman, she went to France for flight school because American schools refused to admit her. Mildred Burke participated in the wrestling circuit in the ’30s. Women’s wrestling was outlawed almost everywhere in the United States, but she managed to win almost every match, including those against men. Hedy Lamarr, born in Vienna, Austria, made her name in Hollywood where she appeared in 30 movies and married 5 husbands. Today, she is also remembered as an engineer for helping Howard Hughes perfect an aircraft wing design and as a pioneer of frequency hopping, a technique which allowed Allied ships to avoid German attacks during World War II.

These are just a few of the women covered in The Color of Time. Jones’s write-ups are intriguing; they left me wanting to know more about the women. They also raised several questions. High level accomplishment is the common thread among the women, but why these females and not others? What criteria were applied? Does a historical thesis underlie the work, other than that these women faced obstacles and did remarkable things?

The introduction to the pair’s first book highlighted the painstaking nature of Amaral’s colorization work. As pointed out there, black and white photos offer little guidance in terms of original colors, so she looks to historical sources, written and visual, before deciding what colors to add. In this volume, though, Amaral offers no hint of why she chose a certain color for a dress, or whether an athlete was really wearing lipstick when the photographer clicked the shutter. And that is disappointing. I could not help but think about the documentary They Shall Not Grow Old, in which director Peter Jackson colorized footage of soldiers in World War I. Of course, it may be an unfair comparison. Jackson had unparalleled access to source material, with the archives of London’s Imperial War Museum and his own extensive collection of military uniforms at his disposal. He even traveled to Flanders to scrutinize the green of the grass where soldiers died.

Not every colorization project can or will be comparable to Jackson’s. It does not appear that this one attempts to duplicate that sort of meticulous historical research. Can we really assume that people and events looked as luscious in real life as they appear here? Probably not. Despite these quibbles, this coffee table book scan of women’s history reads well and is visually striking.

Kathleen Stone is the author of They Called Us Girls: Stories of Female Ambition from Suffrage to Mad Men, published in March 2022 by Cynren Press. Her website is kathleencstone.com.