Visual Arts Review: Illustrations of Race at The Norman Rockwell Museum

By David D’Arcy

Imprinted: Illustrating Race and Kadir Nelson’s In Our Lifetime: Paintings from the Pandemic” at the Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, through October 30.

Norman Rockwell was troubled about race relations in American society, and he let his public know that.

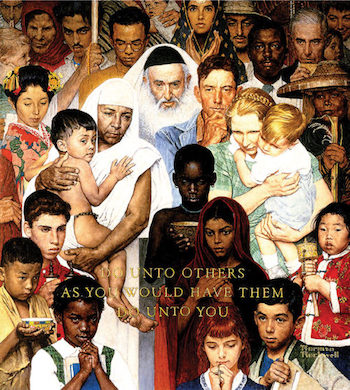

Sometimes that meant simply depicting more than one race, which led to misgivings at his mainstay, The Saturday Evening Post. The magazine was wary of printing the 1961 cover, “The Golden Rule,” which showed a global range of faces. The publication’s policy, Rockwell said in a later interview, was to depict African-Americans only in servile roles.

“The Golden Rule..” Photo: Norman Rockwell Museum.

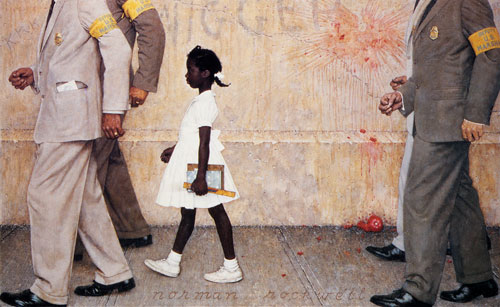

Leaving the Saturday Evening Post after 47 years, Rockwell painted scenes for Look magazine covers that dealt with a country forced to live up to its principles. A memorable image from 1964 was of a six-year-old Black girl in a white dress, Ruby Bridges, being escorted to the school in New Orleans that she was integrating in 1960 by four massive US marshals – so large that they extend beyond Rockwell’s frame. Rockwell’s caption was “The Problem We All Live With.”

In a wrenching scene that Rockwell painted for Look in 1965, “Murder in Mississippi,” a young white man holds a wounded Black man while another white man lies motionless on the ground. Shadows of armed figures extend over the picture from the right. The murder victims were Michael Schwerner, James Chaney, and Andrew Goodman. They had been registering Black voters in Philadelphia, Mississippi. (The killings loosely inspired the 1988 film Mississippi Burning).

The exhibition Imprinted: Illustrating Race, 150 works and objects at the Norman Rockwell Museum, explores a vast subject, the politics of race in popular American print culture. The presentation is more of a sampling than a systematic survey, more history than art. A selection of work by African-American illustrators, many unseen by the white readership, is counterpoised to the demeaning treatment of race in the illustrated press.

Visitors will find some familiar names — Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, Charles White, and Faith Ringgold. There are also contributions from artists whom many won’t know. The show tracks the evolution away from degrading caricatures of Black Americans and the rise of new images made by African-Americans themselves.

Don’t expect a place known as a family museum to display the harshest extremes of printed racism. Or to show the most extreme African-American responses. Yet there are some surprises here.

“The Country We All Live With,” Norman Rockwell. Photo: Norman Rockwell Museum.

Looking over the museum’s website will help prepare visitors for the range of images. So will an exhibition in the same galleries, In Our Lifetime: Paintings from the Pandemic, of work by the painter and illustrator Kadir Nelson (b.1974).

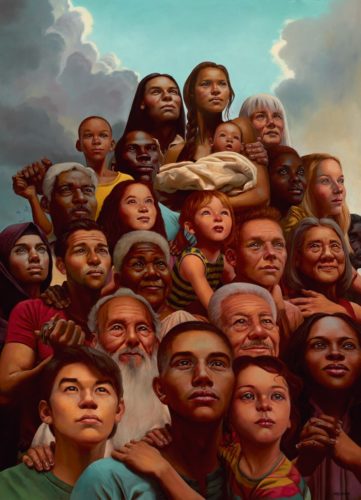

Nelson’s 2020 painting “After the Storm,” is a near-literal updating of the ensemble of faces from multiple races and origins that Rockwell assembled in “The Golden Rule.” It could be that his 2020 portrait of George Floyd, “Say Their Names,” a painted memorial to victims of police killings, is a grim commentary on Rockwell’s image. composed of what looks to be a group of victims of bodies. Rockwell’s ensemble of faces from throughout the world (and the US) suggested a community, or the makings of one. In Nelson’s “Say Their Names,” a New Yorker cover of June 2020, the faces fill a mass grave

In Imprinted, bookended by works by Rockwell and Nelson, we see illustrations from an advertising campaign from the early 1900s in which stories and images of compliant Black servants were used to sell products to children. The product was Cream of Wheat, a cereal that a small firm introduced to the market in 1893. Unknown then in American homes, Cream of White was manufactured in Grand Forks, North Dakota. To sell the cereal to children, or to their parents, its managers devised a magazine campaign of images showing carefree kids attended by a Black cook holding – what else? – a bowl of Cream of Wheat. The standard Cream of Wheat picture was of mischievous blonde children calmed by that Black man with a white bowl.

“After the Storm,” Kadir Nelson. Photo: Norman Rockwell Museum.

The catalogue essay by Michele E. Bogart reads like a case history in sales promotion. Pale in color, Cream of White didn’t look like much. A company executive (“marketer” was not a word used back then) came up with the idea of creating dramatic “scenes’ of the cereal served to children (all white) by a Black man dressed as a chef. The effect that the company was seeking — and selling — was meant to be soothing and reassuring. In the ads, the chef was named Rastus, a name long associated with Black slaves and servants. A man named Frank White was used as the model for those pictures. In her essay, Bogart quotes the executive in charge of the decades-long campaign. He says that White was paid “a few dollars” – about five dollars, other writers say. White then “disappeared,” Bogart writes. The campaign that sold the cereal with his face went on for decades.

Hiring some of the leading artists/illustrators of the time, Cream of Wheat exploited longstanding notions of a deferential, dutiful, gentle icon of otherness, in parallel with Aunt Jemima, launched around the same time in St. Joseph, Missouri.

Every marketing campaign needs to regenerate itself with fresh approaches, so Cream of Wheat turned to producing posters in a style that artists (“fine artists”) made in the early 1900s. In one scene, the children view a framed portrait of Rastus exhibited in an art museum. If the children that piled over each other in front of the portrait weren’t ready for art, the picture suggests, at least they were ready, via Rastus, for the nutritious (and civilizing?) appeal of Cream of Wheat.

Bogart notes that there are holes in the archival evidence that might tell us more about Cream of Wheat’s illustrated campaign. But the seductive sentimental gauziness of the images, which fill far more space than text in the posters, says a lot. They suggest that the pictures targeted children who would demand that their parents buy the cereal – a winning strategy for any marketer.

The presence of art in the illustrations “sacralize” the product, Bogart argues. The presence of a loyal servant assures young children that they will be well fed and safe. Cream of Wheat did not retire Rastus until 2020, around the same time that Quaker Oats abandoned the branded character of Aunt Jemima — also around the time that George Floyd was killed.

In Imprinted, a show curated by women, with catalogue essays written by women, there is also a rare focus on often-neglected Black women illustrators. One is Jackie Ormes (1911-85), whose plucky and witty characters (some looking a lot like self-portraits) were the protagonists of her work for close to twenty years.

First working out of Pittsburgh, Ormes created the character of Torchy Brown, a stylish adventurer who fought off villains and abusers. In this comic strip for the Pittsburgh Courier which, syndicated through other African-American newspapers, reached more than a million Black readers, Torchy’s political consciousness transcended the parameters of the funny pages. Ormes also drew eye-catching clothes for Torchy, which may have attracted more readers.

A panel from Jackie Ormes’s “Torchy” comic strip.

The strip, given that added fashion dimension, might have reached an even broader audience — if major newspapers agreed to carry it.But, like so much else at the time, readership was segregated.

Ormes’s political edge was part of all the work that she did. So was her surprisingly forward-thinking interest in environmental justice, which barely figured at that time in American media. In her strip “Heartbeats,” an African-American nurse (also named Torchy) works with a Black doctor to treat patients threatened by toxic factory pollution in the American South. Bear in mind that these comics were published before the Civil Rights movement drew much attention from the mainstream press.

In 1945, Ormes began “Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger,” a series of panel drawings, single drawings with captions. where the characters were Ginger, a stylish young woman, and her precociously irreverent five-year-old sister. Subjects ranged from wartime victory gardens (tended by the older fashionable Ginger in high heels and a short skirt) and a Halloween scene with a reference to witch hunts. Ormes was suspected of spreading un-American views and investigated for it. One look at the poverty of a Black family in a squalid room was too stiff a reminder of reality for any mainstream publication. That family wondered out loud how the “H-bomb” protected poor people like themselves.

The catalogue essay by Nancy Goldstein (who is also Ormes’s biographer) refers to a racially charged joke in a scene from 1955: “Patty-Jo, speaking to Ginger, who hides a newspaper with shocking cover photos of murdered Emmett Till behind her back, says, “ I don’t want to seem touchy on the subject…but that new little white tea kettle just whistled at me.’” Mocking a white woman’s justification for Till’s death in a comic strip? How many mainstream publications would have imagined running a cartoon like that at the time?

Edward V. Brewer, “Cream of Wheat,” 1921.

As investigators sought to intimidate her, Ormes was also entrepreneurial, developing a doll inspired by the wise-cracking Patty-Jo that was produced between 1947 and 1949. The artist’s life story cries out for a documentary or a scripted dramatization.

If Ormes knew how to weaponize humor, Emory Douglas weaponized anger, even though his cartoonish style could, like Ormes’s, just as easily convey warmth and laughs.

Douglas, who studied commercial art at City College of San Francisco, joined the Black Panther Party (BPP) in 1967. He took the title of Revolutionary Artist. He would later become the BPP’s Minister of Culture. He was the art director, designer and principal illustrator for The Black Panther newspaper until it ceased publication in 1980. If his work had a dominant theme those days, it was self-defense, often in the form of a Black figure, usually a woman, with a rifle in her hand. His captions spat out an attitude, as in the defiant panel from 1971, “Listen to Them Pigs Banging on My Door for Some Rent Money…They Should Be Paying My Rent.” Another work on view by Douglas is a drawing of a Black man with a rifle and what looks like a broken chain on his wrist, 1970’s “Now the Pigs Will Say I Am a Criminal.”

Tough words for the walls of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

For The Black Panther, Douglas’s audience, reaching up to 140,000 in 1970, was still mostly segregated (or self-selected) by race. The artist’s characters tended to be seen holding guns (although there is an occasional woman holding a rat). The depictions of armed citizens, African-Americans asserting their Second Amendment rights, alarmed authorities in California, who hesitated on gun rights when the arms were held by Blacks.

Douglas’s later work, sometimes less confrontational, includes a 1993 portrait of Martin Luther King, Jr. which is on the cover of the Imprinted catalogue. King is shown with arms folded, against an array of yellow spokes on a red background. It’s hard to tell what Douglas was suggesting with that composition, though The Black Panther was far to the political left of King.

In the YouTube video below Douglas talks about his decades as an illustrator and publisher. He doesn’t sound as if he’s softened much.

Among the artists in Imprinted, Douglas has seen his reputation revived, with the publication of a 2014 book on his career and the inclusion of his work in museum exhibitions. His illustrations are unabashedly polemical: these are not the usual kind of pictures found at the Norman Rockwell Museum.

All the more reason for Imprinted and its broad range of images. There are drawings by African-American illustrators that shed new light on the Harlem Renaissance. There are also personal pictures by artists working today, such as Noa Denmon, Andrea Pippins, Rachelle Baker, and Loveis Wise, that veer away from anything explicitly political.

Can we expect future Rockwell museum exhibitions on illustrating delicate subjects like gender or religion?

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: David D'Arcy, Emory Douglas, Imprinted: Illustrating Race, Jackie Ormes, Kadir Nelson

[…] Visual Arts Review: Illustrations of Race at The Norman Rockwell Museum – artsfuse.org […]