Opera Album Review: Richard Flury, A Swiss Composer You Should Know About

A world-premiere recording of Richard Flury’s fascinating 1935 opera about love, deceit, and the possibility of forgiveness.

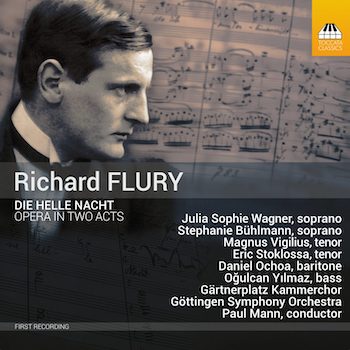

Richard Flury: Die helle Nacht (opera in two acts)

Julia Sophie Wagner (Solange), Stephanie Böhlmann (Céline), Eric Stoklossa (Robert), Magnus Vigilius (a Knight), Daniel Ochoa (the Doctor).

Gärtnerplatz Chamber Choir, Göttingen Symphony, cond. Paul Mann.

Toccata [2 CDs] 107 minutes.

To purchase, click here.

Swiss composers? There’s Ernest Bloch and Arthur Honegger, but they lived most of their adult life elsewhere (respectively: the US and France). Othmar Schoeck is perhaps the best-known one who largely stayed home. But word is spreading about Richard Flury (1896-1967), and many of his compositions are belatedly gaining attention and being recorded — or even receiving performances for the first time. Flury, after extensive training (in part as a violinist) in Switzerland, spent time in Vienna studying further (with Joseph Marx), then returned to teach and conduct in his native city of Solothurn.

Swiss composers? There’s Ernest Bloch and Arthur Honegger, but they lived most of their adult life elsewhere (respectively: the US and France). Othmar Schoeck is perhaps the best-known one who largely stayed home. But word is spreading about Richard Flury (1896-1967), and many of his compositions are belatedly gaining attention and being recorded — or even receiving performances for the first time. Flury, after extensive training (in part as a violinist) in Switzerland, spent time in Vienna studying further (with Joseph Marx), then returned to teach and conduct in his native city of Solothurn.

His works are late-Romantic in style, occasionally more dissonant than, say, Rachmaninoff or Sibelius. Sometimes the orchestration becomes highly coloristic, in the manner of Debussy and Ravel. His works may have been neglected in part because they are relatively conservative for their date. The classical-music world has been obsessed for a century or more (or maybe since Wagner) with whatever could loudly proclaim itself New and Modern and Daring.

Maybe being Swiss is also part of the problem. Other composers born there — such as the three that I named — have likewise not had the kind of national “boost” that often comes from being a representative of a bigger country. (Bloch, furthermore, falls between two stools. I don’t recall his works ever being included in festivals of “American music,” despite his having lived and worked here for decades. Berlin-born Charles Martin Loeffler is another such neglected figure, treated as a mere visitor to America despite having been prominent as a performer, composer, and teacher in the Boston area for most of his adult life.)

Flury was in Switzerland throughout the Nazi years. He probably had a peaceful career because of Switzerland’s neutral position in regard to the German government and policies. (Neutrality allowed Swiss firms to profit greatly from trade with the Nazis.) This in itself may rule his music out for some. But he also befriended and worked with Jewish émigré musicians and other creative artists who had fled Germany (and Czechoslovakia after it was occupied by Germany in 1938-39). I decided to listen to the opera at hand as if I didn’t know any of these biographical details.

Flury is best known (nowadays) for a number of instrumental works. (Most of the previously released recording, in America at least, are for orchestra, chamber ensemble, or solo piano.) But he also wrote four operas, none of which ever got more than a local performance in his lifetime. Thanks to determined efforts by his son Urs Joseph Flury (himself a composer), many of these are finally being recorded. I reviewed here, quite favorably, Flury’s setting of a German translation of Oscar Wilde’s one-act play A Florentine Tragedy. (German title: Eine florentinische Tragödie. Flury’s opera is not to be confused with Zemlinsky’s somewhat more intense setting of the same German libretto, which I likewise reviewed here.)

Die helle Nacht is a more extended work: two acts, with an immensely long scene toward the beginning of the second act (scene 9). Flury derived the libretto from a 1912 verse play by the Austrian journalist (and future diplomat) Paul Zifferer. I like the work even more than I did A Florentine Tragedy (and the impressive concert aria, to a Grillparzer text, that fleshed out that CD). During his lifetime Die helle Nacht received a single production: a 1935 concert performance broadcast by Radio Bern (alas, no recording survives). The present recording is the work’s second performance anywhere; it uses a critical edition of the score prepared by the conductor, Paul Mann.

Composer Richard Flury in 1950

The plot gives us four main characters plus many smaller roles for townspeople. We are in 16th-century Paris, when Mary Tudor (sister of Henry VIII) is being brought to the city to marry Louis XII. A herald announces that the night should be devoted to festivities, with plentiful torches (hence the opera’s title, which means “The Bright Night”). A doctor, unnamed, is tortured by his suspicion that his wife had a one-day affair with an unknown man years ago. We meet the wife, Solange, in conversation with the Doctor’s current student, Monsieur Robert. She is attracted to this ardent young man but declares that she is old now and sends him off to his more age-appropriate girlfriend, Céline. The Doctor arrives and unloads on Solange (as he has so often done) his suspicions about the one long-ago day when he was out of town. She denies all.

Act 2 begins with townspeople pouring into the Doctor’s study and playing carelessly with his tools. Representatives of the Duke arrive with what they say is the corpse of a knight; the Duke figures that it may be of value in the Doctor’s teaching. Left alone with the Knight, the Doctor discovers that the latter is still alive, if barely. The Doctor revives the Knight with elixirs, and the two have a tart and sometimes philosophical discussion about life and love, in the course of which it becomes clear that the Knight was Solange’s one-day lover years ago. The Doctor puts poison in the Knight’s drink, then, feeling remorse, gives him an antidote. The Knight leaves, Solange returns, and the Doctor comes to accept something about the limitations of life and knowledge.

Flury’s musical style in this fascinating opera is very accessible: by turns colorful, depictive, moody, passionate, and emphatic. The libretto includes some songs and a choral prayer (in Latin, over the body that turns out not to be dead), as well as dance music heard through an open window. The vocal lines are shapely and well suited for singing, not just for declaiming the syllables in a heightened-speech manner. At times I was reminded of Hindemith’s opera Mathis der Maler and Pfitzner’s Palestrina, but the music is rarely as portentous and solemn as the latter. At other times, it seemed closer to the more agonized, less songlike sections of Weill’s The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny.

There are some impressive and moving passages for orchestra alone, often accompanying on-stage activity by one or more characters (a bit analogous to the music for Beckmesser’s silent scene in Hans’s workshop in Die Meistersinger). All of this makes me want to get to know Flury’s instrumental works. You can try some of the opera’s tracks out for yourself on YouTube or other streaming services, or at toccataclassics.com.

Baritone Daniel Ochoa. Photo: Christian Palm

The two sopranos, two tenors, and baritone in the main roles are nicely differentiated, easily allowing one to know, by ear, which of them is singing. I have previously praised Julia Sophie Wagner (on the aforementioned Flury CD and in Johann Simon Mayr’s 1814 opera Elena) and have greatly enjoyed Ochoa’s performances (e.g., on that same Mayr recording and in an 1839 oratorio by Ferdinand Hiller). The two tenors here are equally fine. Eric Stoklossa is slightly fuller as Robert, the young student infatuated with the doctor’s wife. Magnus Vigilius, who has sung major heldentenor roles, wields a thinner, reedier tone, almost that of a character tenor, yet hefty when required.

The orchestra plays beautifully. As so often, I notice that smallish cities nowadays have highly professional-sounding orchestras. (Göttingen is basically a college town, like Heidelberg.) Paul Mann conducts with keen insight. The orchestra sounds a bit recessed, compared to the voices. This has the advantage of allowing for much quiet interchange between the singers — and for the text to be easily heard. It also sometimes makes the work feel like a radio opera. Perhaps that 1935 broadcast was quite effective (if the performance was as expert as the one heard here).

The booklet contains helpful essays on the composer and work, as well as the libretto and Chris Walton’s superb English translation. In sum, the performance, recorded sound, and printed presentation add up to a model of how a record firm should present a little-known work.

For more on Flury’s life, career, and creative output, I heartily recommend Walton’s book Richard Flury: The Life and Music of a Swiss Romantic. It is published by Toccata, the same firm that produced this eye-opening new recording.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Die helle Nacht, Gärtnerplatz Chamber Choir, Göttingen Symphony, Julie Sophie Wagner, Paul Mann, Ralph P. Locke