Poetry Review: “Whale Fall” — The Dark at the Bottom of the Ocean

By Alina Stefanescu

It is dark, so very dark, at the ocean’s bottom. And yet, there is also a disquieting, wonder-filled magic in the child’s moon which hovers over these poems; an incantatory moon echoing like a lullaby, drawing on a time of innocence.

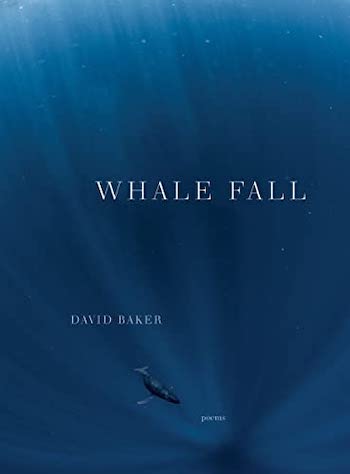

Whale Fall by David Baker. W.W. Norton & Company, 99 pp. $26.95 (hardcover).

When a whale dies, it sinks to the bottom of the ocean floor. If the whale sinks deeper than 1,000 meters, its corpse may become what’s known as a “whale fall,” a site for a complex, localized ecosystem that supplies life, shelter, and nourishment for deep sea organisms. A dead whale can keep other beings alive for decades.

When a whale dies, it sinks to the bottom of the ocean floor. If the whale sinks deeper than 1,000 meters, its corpse may become what’s known as a “whale fall,” a site for a complex, localized ecosystem that supplies life, shelter, and nourishment for deep sea organisms. A dead whale can keep other beings alive for decades.

David Baker’s 11th poetry collection is titled after this carcass-centered aquatic event. A whale fall hosts five trophic levels simultaneously; Whale Fall is divided into five numerated sections, notable for their variance, expansiveness, and sumptuous orchestration. I read this book as one absorbs a symphony, attending the lavish feast of sound and motion with its multiple instruments and silences. The poet knows his orchestra, and he brings every technique to bear on this composition: collage, typography, punctuation, italicization, patterned uses of the em dash, conventional stanzaic structure, as well as structural looseness of unpunctuated, uncapitalized phrasings and fragments. Tiny poems like the single couplet of “Elegiac” nestle beside lengthy ones — the longest of which is the title poem, “Whale Fall.” Numerous lexicons from botany, cartography, pop culture, and natural history inventory both the present and the absent. Accordingly, there is no single time signature, no tempo marking, no consistent beat or pace. Multiple layers of time coexist in titling, from the epochal, as in “Middle Devonian,” to the daily, as in “Six Hours,” to the immediate, as in “This Morning.”

The sole epigraph comes from W.S. Merwin: “Look how I am attached to the end of things.” Palpating the durative tension between a memorial voice and a relational one, Baker ecologizes time, bringing loss into dialogue with the physical. This is a book of zero brio. No macho. No flaunting of muscle. Emotional responses nestle within formal devices and repetitions: the result is an invocative, elegiac voice that resists morbidity.

Many poems are intertextual and collagelike. “Nineteen Spikes,” a portrait of the Covid virus in couplets, draws on local newspaper headlines, CERN’s writing guidelines on nuclear testing, and a field guide to Ohio trees. Baker’s mix of scientific language gathers the viral alongside the nuclear:

Looks like a tiny naval mine. Between 80 and 120 spikes.

Terminal barbs. A special form of moored contact mine.

“Give coronoviruses their name,” the speaker says. “Sweetgum. Storax.”

The imputed power of naming returns in “Mullein,” where the scientific names of plants are in counterpoint to the embodied versions, since “What you call / a thing is seldom what it is.” The speaker turns to the names his father used for family, places, and friends, culling the “litany /of names in his / stories.” Moving back and forth between his father’s namings and colloquial descriptions, Baker evokes a disappearing language where mullein is intimate enough to grow nicknames, to become part of a Midwestern landscape… “beggar’s blanket”; “burning teeth”; “ancient jewel”; “farmer’s bandage”; “ghost-in-shadows.”

“A Portrait of My Father in Seven Maps” is a longer poem with numerated sections, each one carving out a different topographic terrain relating the father to the son across the verdure of criss-crossing pronouns — the child, the I, the he, the We — without using quotations to specify the speaker. As Ptolemy’s ancient maps flit between the father and son, one senses the map makes the man, or the world he offers to a son. But, in the Anthropocene, the mind has moved from conquest to hope for coexistence, one of the global solutions to climate change. The son mourns the “hubris” of cartography in our belief that one can “present the world… As if to say now and forever. ” Colloquialisms, the maps of the past which made the world stable in the mouths of the fathers, are dappled throughout the poem. But they feel antiquated, like cassette tapes, no longer relevant to the world. All seven “maps” end with an em dash, which functions as a jagged ellipsis, a drop-off from the edge of a world before we could agree on its spherical shape.

Intrigued by Baker’s use of em dashes in this collection, I counted and found over 150 lines ending with them. “Thirty-Six Silos”, for example, is composed of 17 couplets which end in em dashes, and double-up in the final stanza:

Now a silo reaching up to the black earth of sky —

Now a silo burning with the half-life of the sun —

Poet Stanley Plumly died on April 11, 2019, and Baker’s abiding love for Plumly stretches across this book, burying itself in quotations, memories, and landscapes. The dolor of “Turner’s Clouds for Plumly” meets the elegy in ekphrasis, specifically, in a shared fascination with William Turner’s paintings of clouds and seascapes. The speaker addresses Plumly across time, referencing one of his late books, Elegy Landscapes: Constable and Turner and the Intimate Sublime.

In books he calls paintings the landscapes of

water, wild beyond human artifice.

They are what our feelings are without us.

Baker draws us into a prior conversation with Plumly. “We live in one time but think in another,” he says, and continues:

When he saw the paintings again, the cloud

symbols, the impressionist’s weightless swirls,

he must have felt something airy

and ominous coming down, the way each

canvas is an art of premonition.

In love we open our mouth. In dying

we open it wider, saying, he wrote,

in your voice, come forth.

The phrasing pulses with awe, affection, and marvel; the speaker’s voice shades into that of the interlocutor, the painting, the artist, Keats talking to Coleridge, two friends, the sky.

I wondered if Baker drew some dew from the title of Plumly’s book, since Whale Fall is an “elegy landscape” made from whale bones and oceans and patches of luminosity, the “intimate sublime.” Plumly’s presence is continuous, reappearing in “One September” and “Six Hours,” among others. Even “Whale Fall” — the titular poem, which straddles the entire third section — returns to Plumly, using italics to quote him: “You know I am serious about the whales.” Intertextuality is central to the construction of this poem’s swarming polyvocality, the collage of references, media, and quotations. We learn the names of feeders at various stages in the whale fall; sonic effects with language (“bathyal, abyssal”); the sperm whale found dead with “a plastic spray canister in its stomach”; the hummingbird sipping from red sugar water as “bubbles aerate, like an aneurism”…

The aperture is broad and dizzying; it resembles the chaotic inventory required after the death of a loved one, or the list that turns objects into memorials. Richness feels like a form of paucity, reminiscent of an adult speaking rapidly to a child to distract them from a bleeding wound that will require stitches. When the adult goes silent, the wound waxes in salience. But words don’t heal broken skin, and explanations fail us. The poem’s gaze flickers between marvel, concern, and the disappointment of the child who has discovered adults do not know how to speak to the moon at all.

Poet David Baker. Photo: Poetry Foundation

Collage also inflects “Echolocation,” a poem about pandemic loneliness, a time out of time. Beginning with “In our year of distances,” Baker then quotes an untranslated phrase from Henryk Gorecki’s Symphony No. 3 – “O, nie placz, nie” – which means “O, don’t cry, no.” The speaker tells us he listens for voices, and they arrive over five pages of sprawling tercets: the unhearable, echolocative communication of deep-diving beaked whales, echoes from Margaret Wise Brown’s Good Night Moon, dialogues with lines from Jean Valentine, Theodore Roethke, and Jack Gilbert, the shadows of whales in the ancient Cambrian ocean, memories of the small mountain village of Zakopane in Poland, echoes bouncing off echoes. And the em dash makes its appearance at the end of every first and third line in the tercets.

The effusion of collage contrasts with the controlled precision of poems like “We Are Gone,” “So Far,” and “This Morning,” with its meticulous symmetries (four eight-lined stanzas), repetitions (each stanza repeats the first line as the last line), and modulations (the last stanza ends with the first line of the poem). Relying on internal rhymes, the poem paces itself melodically, surprising us with the images: “a new peony opens to morning—big as / a softball–so heavy it falls to the grass.” One is struck by the deception hidden inside the word softball, which is not soft at all; one remembers how much it hurts to be hit by it. Baker’s poems abound with unforgettable, incongruous images like this one.

A whale fall reveals patterns of ecological succession; its finale is the “reef stage,” where fat depleted bones are consumed. The pacing and monosyllabic rhymes of “So Far” reminded me of these depleted bones. An elegy isn’t always a lamentation. In this poem, whose only proper noun is the plant known as Queen Anne’s lace, an elderly woman has died, possibly a family member, and the speaker navigates her final disposition with his partner. Their walk towards the river is punctuated by silences, by “the rustle of the trestle” and memories of the deceased. The two stop at a special spot where “the water turned”:

It going with us. Dropped her in. Urn made

out of salt. She wanted to be that way,

ashes writ in water. So you say. You

there in the whisper. The birds sunk into

some limbs’ hollowing green shadow.

When I die, will you be there? Will you

watch me go? Turned back for the car.

Her going with us. Having flowed so far.

The fragments are punctuated with sharp, needly periods. Here, abrupt syntax serves as a decelerant, which enables us to inhabit the meditative, unexpected changes in direction and texture.

What to make of the four untitled, interludic poems staggered throughout the book (the table of contents culls a title for each from its first fragment)? “Is there no sound to,” for example, is one long question broken across lines and space:

nowhere cloud landscape of silence stopping

through the night my sleep a dream of falling

beyond anywhere you might be listening—

Written completely in italics, arranged as diptychs or triptychs, the untitled quartet brought orienteering to mind, or the challenge of locating one’s self on a map. And how orientation influences the direction in which a map is read, depending on where we begin or end: “and to whom to what —”.

Baker orchestrates a swirling momentum from found words, from memories, from the echo of the echo of the siren, from the hushed terror of chronic illness. It is dark, so very dark, at the ocean’s bottom. And yet, there is also a disquieting, wonder-filled magic in the child’s moon which hovers over these poems; an incantatory moon echoing like a lullaby, drawing on a time of innocence. Perhaps there was a time when adults could be trusted with language. Baker reveals poets can still be trusted with our most precious landscapes.

Alina Stefanescu was born in Romania and lives in Birmingham, AL, with her partner and several intense mammals. Recent books include a creative nonfiction chapbook, Ribald (Bull City Press Inch Series, Nov. 2020) and Dor, which won the Wandering Aengus Press Prize (September, 2021). Her debut fiction collection, Every Mask I Tried On, won the Brighthorse Books Prize (April 2018). Alina’s poems, essays, and fiction can be found in Prairie Schooner, North American Review, World Literature Today, Pleiades, Poetry, BOMB, Crab Creek Review, and others. She serves as poetry editor for several journals, reviewer and critic for others, and co-director of PEN America’s Birmingham Chapter. She is currently working on a novel-like creature. More online at www.alinastefanescuwriter.com.