World Music Album Review: Bassist Alune Wade’s Brilliant “Sultan” — A Global Patchwork Quilt

By Allen Michie

Sultan has a solid lock on my year-end best of 2022 list. Let’s make the world a little smaller and make this album a hit.

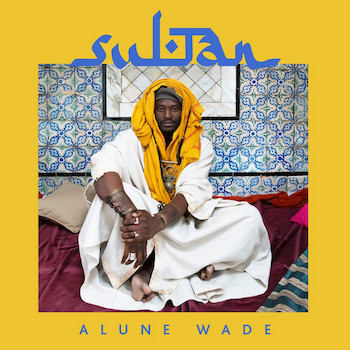

Alune Wade, Sultan (Enja and Yellowbird)

Now THIS is the way to make an album. Go straight down your list of the way you like music to be: funky, lyrical, soulful, exotic, grooving, multicultural, honest, political, emotional, intimate, well-produced but not slick, varied, jazzy, rocking, historically aware, experimental, tight, cliché-free, effectively arranged, diversely instrumentalized, thick with percussion and bass, thematic, cinematic, and ambitious without being pretentious. All of this and more describes Alune Wade’s Sultan.

Now THIS is the way to make an album. Go straight down your list of the way you like music to be: funky, lyrical, soulful, exotic, grooving, multicultural, honest, political, emotional, intimate, well-produced but not slick, varied, jazzy, rocking, historically aware, experimental, tight, cliché-free, effectively arranged, diversely instrumentalized, thick with percussion and bass, thematic, cinematic, and ambitious without being pretentious. All of this and more describes Alune Wade’s Sultan.

Wade is a virtuoso electric bassist from Senegal, and he’s a protégé of Marcus Miller. He has Miller’s same deep thump, which isn’t overdone, and he shares the same ear for atypical funk lines. Miller asked Wade to contribute as a composer and vocalist on his 2015 album Afrodeezia. Miller’s associations lean toward the more commercial sides of jazz and R&B, whereas Wade’s list of musical partners cuts across continents and genres: Salif Keita, Oumou Sangaré, Bobby McFerrin, Joe Zawinul, Fatoumata Diawara, Paco Sery, Wolfgang Muthspiel, Bela Fleck, Cheick Tidiane Seck, Deep Forest, and Gregory Porter.

Wade is dedicated to using music to bridge international borders. His 2015 album Havana-Paris-Dakar is a good example. It gives North African music a Parisian twist with assistance from Cuban pianist Harold López-Nussa. Sultan was recorded in Paris, Brooklyn, Dakar, and Tunis. That alone should suggest the styles of music on this recording. Wade’s ambition for Sultan is to create “an open composition in a pluri-millennium era which is capable of surrounding itself with different sensitivities in order to retrace humanity’s voyage and unite the rhythms of their languages.” Note he doesn’t say different genres, styles, or nationalities. He says “different sensitivities.” That’s what keeps this global patchwork quilt from becoming a disunified mess. It moves between sensitivities, which the music demonstrates are not really that different across cultures after all.

Wade also produces, does some of the vocals, and writes the arrangements on Sultan. The latter are complex, creative, and deeply informed about different world music approaches. They’re also tight, funky, and fun. These are not shapeless jam sessions: each song has a direction, a thematic purpose, and a melodic focus. Each element of the arrangements earns its keep and is there for a reason, often explained in the informative and ear-opening liner notes. For the track “Nasty Sand,” for example,

The seductive binary rhythm is not there by chance. It is there to hook you and focus your attention on the message the artist has decided to pass on…. The melodies cross over between continuity and the mixing of cultures, a guitar and bass riff picks up on the Gnawa rhythms, as brass instruments play both the African and American blues. Wade designates the pianist as the storyteller who stitches together a link between the blues brought back by the deportees (ex-slaves) and their European instruments and ancient African instruments…. A deconstruction, then reconstruction, which follows the movement of populations which migrate.

I’ll highlight just a few of the 12 tracks to call attention to the range of approaches on Sultan. Passages in quotation marks are from the liner notes.

The second track, “Donso,” begins with some soothing percussion, Cédric Duchemann’s floating piano solo, and Dramane Dembele’s brief but expressive flute “saluting Mother Nature.” Then the tune transitions to a much faster strong polyphonic rhythm indicating “animals moving forward, sometimes interrupted by a cry.” The African group chants over the North African rhythms are powerful. The instrumentation drops in and out, just as background colors would shift to bring parts of a painting into the foreground. The whole thing moves, in tribute to the “proud and intrepid Wolof warriors, born out of the ancient kingdoms of Senegal, Gambia and the south of Mauritania.”

“Sultan” is about the dunes. It conveys “the odyssey of the Sultan who, like the Queen of Sabah, crisscrossed the continent, and starts in a tent. We feel the heat of the desert, and we imagine the procession, the perfumes, the rites.” The Middle Eastern singing of Mounir Troudi wanders freely across the 6/8 rhythm, punctuated by the horns. The quarter-tones and impassioned cries take you far from Western expectations of what music can express. The impression is of circles within circles, with “musicians in harmony, listening to each other, call-and-responses, delivering messages in which the subtle composition transforms itself, both in time and space.” American listeners should take note of the reminder: there is much more to call-and-response than what’s found in the blues and jazz traditions. Keeping with the wildly intersectional global approach, the track ends with a trumpet playing something like an improvised classical baroque cadenza.

“Nasty Sand” introduces straight-up rock and roll to the mix. It features Guimba Kouyate on riffing guitar and Wade throwing down on bass. This kind of grinding African soul/funk/rock just kicks plenty of multicultural butt. It’s a killer track that does what it promises to do, which is to provide “a symbol of the ongoing struggle in the evil sand, that of petroleum, which brings no joy to the African continent.”

“Uthiopic” makes it sound perfectly natural to have a fusion of rap, outside jazz, R&B, hip-hop, and Afropop. The complex drum patterns wouldn’t sound out of place on Miles Davis’s On the Corner. Up-and-coming jazz star Christian Sands on piano keeps the track reaching for the boundaries. The lyrics are in three languages, and there are contributions from Senegalese rapper/poet PPS the Writah. The interaction of melody, harmony, and rhythm will keep you coming back for multiple listenings. Sands solos again on the jazzy “Djolof Blues,” which is “the history of Senegal played to a blues you could call national.” Sands begins by setting a jazz club vibe, aided by Hugues Mayot’s cool soprano sax, but he builds up the dissonance until he brings it to a thundering conclusion. “Lullaby for Sultan” keeps Sands and ups the jazz ante with drummer Lenny White. A recurring chord progression makes this more of a traditional jazz song, although the atmospheric Ethiopian melody keeps the proceedings mysteriously evocative. Wade takes a fretless solo that brings to mind Jaco Pastorius.

“Portrait de Maure” is a standout track among these standout tracks. “The song studies the African youth who must face its realities, scrutinize the world they live in and must try not to swim against the tide.” Far from setting an oppressive tone, this is a bright, uplifting, and fast-paced track. Percussionists Cheikh Anta Ndiaye, Adriano Tenorio, and Paco Sery keep things driving forward. It’s good to hear a bit more of Wade’s solo work. Just when the track settles into one groove or melody, it expands or extends it, keeping the track engaging and exciting. It’s the first single from the album, and here’s hoping it makes it onto some of the progressive playlists out there. Eclectic public radio shows and college stations need to discover this one. Ditto for “Célébration,” a joyous Bollywood-style throwdown. It reminds me of Marcus Miller’s raucous “Blast” from his 2008 album Marcus (or the even better version on 2010’s A Night in Monte Carlo). “The percussions are intimately linked to our vital rhythm because we must celebrate life, birth, loss, mourning, and album. It’s a struggle.”

“L’Obre de L’âme” is a ballad that mourns Wade’s parents. The modal melody is expressive, somber, and difficult to pin down on a map. (Music theorist Anna Brock described the mode as “two Phrygian superimposed tetrachords,” but that only approximates the Middle- and Near-Eastern sound, something like an Islamic call to prayer with memories of Pakistan.) Ismaïl Lumanovski is a revelation on clarinet: when he plays in harmony with Wade’s arco bass you’ll check the liner notes twice to confirm that what you are hearing isn’t some kind of electronically altered sitar. It’s a beautiful and (to my ear) completely original sound that only a master arranger could invent.

Sultan has a solid lock on my year-end best of 2022 list. Let’s make the world a little smaller and make this one a hit.

Allen Michie works in higher education administration in Austin, Texas.

Tagged: Alune Wade, Enja and Yellowbird, Havana-Paris-Dakar

Hello,

Alune Wade is performing at Scullers in Boston on Jan 20, 2023. Hope you can make it.

Marla Kleman

Artistic Director/Scullers Jazz Club