Visual Arts Review: Clark Art Institute — America Discovers Rodin

By David D’Arcy

Rodin in the United States: Confronting the Modern is the show of the summer in the Berkshires — remarkably extensive, with 25 works on paper and 50 sculptures in terra cotta, plaster, marble, and bronze.

Rodin, “Cupid and Psyche,” before 1886. Marble with original wood base. Iris Cantor Collection.

There’s plenty of art to see in Western Massachusetts this summer.

Your first stop should be the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown for the scholarly Rodin in the United States: Confronting the Modern, which runs through September 18. This is the show of the summer in the Berkshires — remarkably extensive, with 25 works on paper and 50 sculptures in terra cotta, plaster, marble, and bronze (including a bust of Rodin by his pupil and lover Camille Claudel).

Besides seeing sculptures and drawings that remind you how central Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) is to the history of art, you’ll learn why he was initially perceived as an interloper, a nuisance to institutions in France, before he eventually became a national treasure. The French government created the Rodin Museum in Paris from his estate.

And you’ll see how his work caught on in the United States, in the usual way it does here: a trickle of prominent collectors bought his art and gave it to major museums.

Son of a low-level police clerk, Rodin was rejected three times by the elite École des Beaux Arts in Paris. For decades, he toiled (and starved) while serving other artists as well as working on decorations for buildings. He did not have his first one-man show until he was forty. But Rodin’s ambition was enormous, even greater than his famed libido, which this show leaves unexplored.

Rodin could also draw, wondrously – not sketches for his sculptures, but works inspired by them. He also drew objects from antiquity, another crucial inspiration. You’ll find some unexpected affinities in those works on paper with the sensuous art of Gustav Klimt, active in Vienna at the same time. (Even in France, erotic drawings were easier to sell than sexually-themed sculptures. German-speaking countries were an eager market.) Yet we don’t look at Rodin because his work reminds us of anyone else – unless that someone else is Michelangelo.

What do we see in Rodin? One of Rodin’s students observed that “the subject of Rodin’s sculpture was sculpture itself.”

Sometimes that vision of sculpture was too raw for the French art establishment in the 1870s to accept. Rodin said that his “first good piece of modeling” was for the “Mask of the Man with the Broken Nose” (original 1864-5), and it is as rugged as any topography of a face as you are likely to find in a sculpture. A bronze cast of that work, from which the back broke off and was left off by Rodin, is on loan from the Rhode Island School of Design

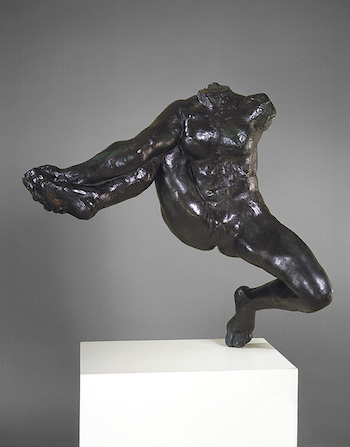

Rodin, Study for St. John the Baptist, today known as “The Walking Man,” assembled c. 1899. Bronze, cast by Alexis Rudier], 1903. National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Rodin, who earned a living sculpting body parts for other artists before he exhibited his own work, often seems to be assembling fragments. “The Walking Man” (1877) is an energetic figure even without arms or a head. In many figures cut out of squares of marble, Rodinn left half the chunk of raw stone untouched. Rodin himself did not cut stone; that job was done by studio professionals called practiciens, under his direction.

Also at the Clark is Rodin’s bust of St. John the Baptist (1880), a martyr who appears to be drawing his last breaths. His body looks torn away from above the shoulders – a reminder that the saint’s martyrdom came at the whim of a young girl in the court of King Herod.

By 1880, Rodin had enough admirers among Parisian dealers and critics to ensure that his work was seen. That led to government grants for ambitious projects that were deliberately erotic or suggestive by French standards, or just gruesome. One such commission: “The Burghers of Calais” (original 1887), a group of figures facing death inspired by elders of that city who, in 1346, offered to give their lives to stop an English invasion of Calais. “The Gates of Hell” (begun 1880), a grand construction around two massive doors, was commissioned by the French government.

The exhibition’s detailed catalogue notes why Americans were wary, at first, of Rodin’s work. Had they known how he worked, they might have been warier. Rodin kept a huge inventory of body shapes and appendages that he sculpted or cast or just snatched from his own existing figures. His detractors used the epithet “Frankenstein.” After his death, surrealists shocked the public by approaching the making of a work of art as an “exquisite corpse” composed of scavenged elements. To their chagrin, they discovered that Rodin had been doing that kind of thing long before.

Rodin never visited America. He was exhibited in the US, without much attention, as early as 1876. In 1893 three of his sculptures were shown at the World Columbian Exhibition in Chicago. They were quickly removed from public view despite — or perhaps because of — what one journalist called a “rigorous truthfulness.” Theywere shipped back to Paris unsold.

In 1898, a collector tried to donate the headless, one-armed and defiantly erotic “Iris, Messenger of the Gods” (1895), balanced on one foot, with legs spread wide, to the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. The museum accepted the gift, and traded it away half a century later for a few small Rodins and other works.

Rodin’s ambition was huge, sometimes so grand that his projects could not be completed. “The Gates of Hell” (begun in 1880), a precursor to what we might now call an installation, was to be an array of sculptures arranged around portals intended to be the entrance to Hell in Dante’s “Inferno.” The ensemble was planned as a doorway to a design museum in Paris that was never built. Rodin’s “Thinker,” modeled on Dante and originally called “The Poet,” was part of “The Gates of Hell” mise-en-scène. Shown twice at exhibitions during Rodin’s life, the “Gates” project foundered under the weight of its own logistics — even with the support of the French government. Various figures and pairings from that work became individual sculptures. American collectors were among the buyers of those works.

We see the monumental side of Rodin at the Clark in a nine-foot bronze cast of the writer Honoré de Balzac in a floor-length robe – which Balzac was said to wear when he wrote, which was all the time. It’s one of three sculptures of Balzac in the exhibition. (Rodin made seven more studies, none in this exhibition, of a nude Balzac, who happened to have been fat and a lot shorter than nine feet. Rodin himself was about five-foot four, perhaps shorter.)

One version of Balzac at the Clark is a terra cotta bust of a man that Rodin chose as a model after he searched around the city of Tours, Balzac’s birthplace, for someone who resembled the prolific novelist. Rodin asked the man, a cart driver named Estager, to grow his hair longer, as Balzac’s was. There’s a resemblance, but Rodin’s likeness of Estager is so precise and distinctive, as Rodin’s portrait sculptures usually are, that we end up with a bust of Estager — not of Balzac.

Rodin, “Iris, Messenger of the Gods,” original model 1895. Bronze, cast by Alexis Rudier, probably c. 1950. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Collection, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Another Balzac bust, on loan from the Legion of Honor in San Francisco, abandoned exactitude for an iconic head atop a stone pedestal that was almost 17 inches high. Rodin was not portraying Balzac as a man from Tours. This was a model for something mythic.

The standing “Monument to Balzac” has a head cast from that smaller bust — once again Rodin was recycling existing elements. In this towering sculpture of the writer, Balzac’s head, with its hawk’s beak of a face, is held high – it is the only part of his body that we can clearly see. All that is visible besides that is hair and cloak. Rodin sacrificed some of Balzac’s likeness to give us his presence. The Clark is exhibiting the work, alone, in a ground floor gallery, upstairs from the main exhibition. Indoors, the monument is still striking in the natural light.

Yet the government agency that commissioned the “Monument” rejected it. Officials, crying “la patrie en danger,” claimed that they couldn’t recognize Balzac in the piece, even as Monet, Cezanne, Gauguin, and Rodin’s student and former lover Camille Claudel countered with praise. “I’m not a photographer,” was Rodin’s response to critics who demanded verisimilitude, although many works at the Clark show how good he was at it. In 1877, when he exhibited the life-size nude “The Age of Bronze” in Paris, he was accused of casting that staggeringly realistic work from a live model, and suspected of casting forms as a convenient short-cut, rather than sculpting them. It would not be the only time that he would face that charge.

Wealthy Americans on both coasts gradually took to Rodin. Andrew Mellon, the Pittsburgh banker who would later be Herbert Hoover’s Secretary of the Treasury (and the founder of the National Gallery of Art), was an admirer. Known as something of a prude, Mellon still bought Rodin’s sculptures for the National Gallery, but died before that museum opened.

In Philadelphia, a Rodin Museum opened in 1929 thanks to Jules Mastbaum, a collector who may have first seen Rodin’s work in 1900 during a trip to Paris as a buyer for Gimbel’s department store. Mastbaum had made a fortune as an owner of lavish movie theaters. A man who understood spectacle, he bought Rodin casts for both his home and for the movie palaces. Mastbaum died before the opening of the museum that presented “The Gates of Hell,” but New York Mayor Jimmy Walker spoke at its opening about what drove this American to collect and exhibit Rodin’s sculptures. Because he loved Rodin, “he was unhappy until he could share this stupendous joy in Rodin’s work,” Walker explained. “There were those who, because of limited circumstances, would never have learned of the works of Rodin if they had remained over there in France. And Mr. Mastbaum felt that because there were some who could not go abroad to see these things he would bring Rodin to them here.”

There were other enthusiasts, like Katherine Sevey Simpson. She and her lawyer husband collected Rodin sculptures and gave them to the National Gallery — rather than to the Met, where the couple had been patrons. They believed that the then-new museum needed the works more.

Rodin, “The Kiss,” original model c. 1881–82. Bronze, cast by Griffoul and Lorge, 1888. Baltimore Museum of Art.

A revealing photograph shows Katherine Simpson in Rodin’s studio wearing only an undergarment over her upper body. This was a risqué picture for that time. She swoons with satisfaction as Rodin seems to be chipping away at a block of marble from which he’s made a bust of her. That bust, from 1903, is also in the show.

Never mind that Rodin never cut stone himself, leaving that job to studio workers. He could have been brushing away dust. The picture reminds us, as biographers have noted, that he knew how to charm his collectors, many of whom sat for him. Their portraits in bronze and marble are not among his most adventurous. Rodin understood the politics and the politesse of courting patrons.

Another object tells us more. It is a plaster mask that Rodin made in 1902 from a mold of Katherine Simpson’s face, with her features arranged as if the mask were a work from ancient Greece – simple, elegant, radiantly life-like, yet iconic at the same time. It is the work of a man who esteemed the art of antiquity above almost everything else. It’s exquisite, but also an expression of tender affection.

By the ’50s, though, Rodin had gone out of fashion, like the subjects of his sculpture, Balzac and Victor Hugo. In the age of Abstract Expressionism, representational art — with some exceptions — was considered about as modern as the buggy whip. Then, in 1955, the Museum of Modern Art acquired a cast of “Monument to Balzac” and placed it in the museum’s courtyard sculpture garden. The person behind that move was MoMA’s founding director Alfred Barr, who called the work “one of the very great sculptures in the entire history of Western art.” Barr’s gesture against the fashion of the times, which the art world couldn’t ignore, enriched his museum and helped re-build Rodin’s reputation.

Rodins continued to enter US institutions, thanks largely to the philanthropy of the financier B. Gerald Cantor, an ardent fan with a mission and the funds to advance it at Stanford University and elsewhere.

The infusion of cash worked. By 1960, The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, a long-running television comedy about American teenagers, featured its perplexed protagonist soliloquizing on life and romance alongside a colossal copy of “The Thinker.”

How much more American can you get?

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.