Book Review: “Making Tracks: A Record Producer’s Southern Roots Music Journey”

By Ed Symkus

A music aficionado-turned-record producer shares his indelible memories of life on the road and in the studio, working with such artists Sleepy LaBeef, Irma Thomas, James Booker, Solomon Burke, Buckwheat Zydeco, and Ruth Brown.

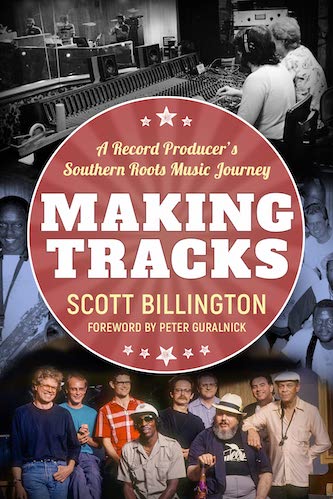

Making Tracks: A Record Producer’s Southern Roots Music Journey by Scott Billington. University Press of Mississippi, 321 pp., $25 (hardcover)

Full disclosure: I’ve known Scott Billington for a long time, going back to our days working together at New England Music City, when new album releases on the front wall included John Lennon’s Imagine, Carole King’s Tapestry, and Isaac Hayes’s soundtrack to Shaft.

While I was one of the record store’s general rock experts, Scott was a fount of knowledge on the blues. He educated me in the genre, with introductions to albums by Little Walter, Willie Dixon, Magic Sam, plenty more. If customers asked me for something good by Skip James or Son House or Sister Rosetta Tharpe, I would refer them to Scott.

Of course, spending eight hours a day in a record store will expand your musical horizons, and Scott’s were wide, but he was — and still is — laser-focused on the blues. He also happens to be a hell of a blues harp player. Add to this his post–Music City experiences at Rounder Records — first as a sales rep, then album cover designer, then art director, then in what turned out to be his sweet spot, as a producer. Now he’s written the blues-centric book Making Tracks: A Record Producer’s Southern Roots Music Journey.

The book proves that he has a great memory for details, is a terrific storyteller, and has worked with more than a few musicians of note over the past four-plus decades. Among them were Sleepy LaBeef, Irma Thomas, James Booker, Solomon Burke, Buckwheat Zydeco, and Ruth Brown, each of whom made records he produced, all of whom are discussed in Making Tracks.

The title is a wonderful double entendre, in that the book lays out a series of reminiscences about the songs — the tracks — Billington produced, and it documents his time on the road — actually making tracks — driving from town to town throughout the South to meet, get to know, and create music with these folks.

Early on, he writes that “the craft of record production is to use the studio in a way that is invisible, so nothing distracts from the feeling and the art.” This makes it sound like the volume could be a dry, nuts and bolts account of what goes on in a recording studio, but the book is anything but that.

Because Billington relates all of this in the first person, he maintains an anecdotal and conversational style, and keeps things light and breezy. He explains that part of his job as a producer is to hire musicians to complement the artist he’s recording, to bring in songs that he thinks would be good for particular artists, and to get someone to arrange those songs. He also gives brief histories about — and insights into — the musicians, and recounts what he remembers about his sessions with them.

There are offbeat tales of rockabilly king Sleepy LaBeef’s unpredictability — onstage as well as behind the wheel of his Cadillac — and of blues belter Solomon Burke’s penchant for selling pork chops backstage at some of his shows. Billington shares some admiring thoughts. Of blues pianist James Booker, he writes, “He was the Vincent van Gogh of New Orleans — a brilliant and troubled artist who was only fully appreciated years after his death — and the only person I have met who might have been what we call a genius.” And he makes note of instances when things didn’t work out the way he had hoped, such as the time Dizzy Gillespie was sitting in for a recording with the Dirty Dozen Brass Band. “Dizzy seemed tired,” he writes. “I kept trying to guide the session back to something more concise. It was not easy, on so many levels, to give direction to Dizzy Gillespie…. At the end of the session, we were crestfallen. We did not have a usable track.”

Music producer Scott Billington pictured with singer Ruth Brown. Photo: Barbara Roberds

But the book isn’t just about music. Much of it passes as a beautifully written travelogue, with detailed descriptions that give you a feeling of place and history. In a reference to the rural area outside the southwest Louisiana cities of Lafayette and Lake Charles, Billington observes that its “many people raise, grow, trap, or catch at least part of their food supply, the legacy of a subsistence culture that has not entirely disappeared. In the flat ‘Cajun Prairie’ around Eunice, rice fields are flooded and transformed into crawfish ponds in the winter, while cattle graze in wide-open fields.”

The only quibbles I have with Making Tracks are that Billington waits until the conclusion to discuss his initial experiences at Rounder Records, when information like that might have served a stronger purpose early on; and that a couple of chapters near the end — one on zydeco music, another on rhythm and blues — border on giving short shrift to some lesser-known artists whose stories appear to be just as interesting as those who received more coverage.

But those are minor complaints, and they’re more than made up for by Billington’s fond and detailed memories of a rewarding career and the people who were a part of it. One of my favorites is his recollection of a 2019 visit to Sam Phillips Recording Studio in Memphis: “I was invited to see Sam’s upstairs office and desk, with a Formica kidney-shaped top, complete with cigarette burns that might have been made by anyone from Charlie Rich to Johnny Cash.”

Ed Symkus is a Boston native and Emerson College graduate. He went to Woodstock, is a fan of Harry Crews, Sax Rohmer, and John Wyndham, and has visited the Outer Hebrides, the Lofoten Islands, Anglesey, Mykonos, the Azores, Catalina, Kangaroo Island, and the Isle of Capri with his wife Lisa.

A sweet little review, such fun to read, and I will never forget that apt description of troubled genius James Booker as “the Vincent Van Gogh of New Orleans.”

Ed; thanks for the preview. I already have the book waiting in the wings, next up to read. As a lifelong record/music person I look forward to leaning in to Scott’s stories of music, musicians and culture I also love very much. James Booker’s talent was immense and vastly under appreciated.