Book Review: The Fascinating Story of “The Method”

By Tim Jackson

Isaac Butler’s stories about The Method’s effect on American film acting are insightful, particularly when he recounts how actors could be either inspired or angered when they embraced it.

The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act by Isaac Butler. Bloomsbury Publishing, 512 pages, $27.

Author Isaac Butler traces the history of Method acting from Konstantin Stanislavski’s initial “System” to its transformation into what later became known as “The Method.” He follows the ups and downs of the Russian technique through its numerous incarnations, diversions, and adaptations. And he digs into the historical context as well: Butler traces the impact of politics, in Russia and then America, on the work of the Moscow Art Theatre (MAT). In New York, Stanislavski’s principles and standards changed the way actors approached their craft and training. His practical ideas, concepts, and exercises for naturalistic acting were espoused by some of the most influential acting teachers of the 20th century: Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler, Sanford Meisner, and Uta Hagan. Each emphasized a different facet of The Method through theories and exercises that were tailored to concentrate on process: psychological (Strasberg); sociological (Adler); behavioral or “living truthfully under imaginary circumstances” (Meisner); a combination of skills emphasizing observation and focus (Hagan). The goal was the same for all the educators: to achieve greater authenticity in performance

Author Isaac Butler traces the history of Method acting from Konstantin Stanislavski’s initial “System” to its transformation into what later became known as “The Method.” He follows the ups and downs of the Russian technique through its numerous incarnations, diversions, and adaptations. And he digs into the historical context as well: Butler traces the impact of politics, in Russia and then America, on the work of the Moscow Art Theatre (MAT). In New York, Stanislavski’s principles and standards changed the way actors approached their craft and training. His practical ideas, concepts, and exercises for naturalistic acting were espoused by some of the most influential acting teachers of the 20th century: Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler, Sanford Meisner, and Uta Hagan. Each emphasized a different facet of The Method through theories and exercises that were tailored to concentrate on process: psychological (Strasberg); sociological (Adler); behavioral or “living truthfully under imaginary circumstances” (Meisner); a combination of skills emphasizing observation and focus (Hagan). The goal was the same for all the educators: to achieve greater authenticity in performance

Acting style in the 19th century, still discernible in the early days of silent film, emphasized the physical manifestations of performance. The approach was exemplified by the Delsarte method: a codified system of physical and vocal gestures. The MAT, founded by Stanislavski and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko in 1898, specialized in a psychological approach to creating characterizations. This undertaking called for going through demanding exercises, often obsessively so. Ensemble work was key, as was the idea that there are “no small parts only small actors.” In Tolstoy’s essay “What Is Art,” he defines acting as “the manifestation of feeling expressed externally.” This mantra was at the core of The Method: actors needed to be penetratingly introspective. They were required to go deep into themselves to express the essence of their characters.

The successes and failures of the MAT’s productions are explored in their specific historical contexts. The company’s first production in 1898 was The Seagull. Stanislavski was only half aware of what he was doing. In his autobiography My Life in Art, the director explains that he wanted to create “living, truthful, real life, not commonplace life, but artistic life.” Chekhov found the production “fussy,” but the crowd that night was awed. Stanislavski told Chekhov that the playwright didn’t understand his own play. That kind of braggadocio would create conflicts for Stanislavski in the future, but the evening changed the face of acting.

Throughout its evolution, MAT’s System faced harsh opposition as well as partisans who wanted to rejigger its definition. Director Gordon Craig rejected realism. “If there is a thing in the world I love, it is a symbol,” he declared. Vsevolod Meyerhold, a contemporary of Stanislavsky, thought of actors as “übermarionettes” whose job was to master the mechanisms of the body. Michael Chekhov employed what he called the “psychological gesture,” the aim of which is “to influence, stir, mold, and attune your whole inner life” in a single gesture.

When the MAT came to New York in 1923, its impact was profound. The group’s performances and workshops changed the way American actors approached their craft. One revealing comment: MAT was like “the coming of a new religion which could liberate and awaken American culture.” Stanislavski’s ideas were perfectly aligned with the naturalism embraced by rising American dramatists, including Clifford Odets, William Inge, and Tennessee Williams. The apostles of Richard Boleslavsky (whose book I found in the outdoor bargain bin at the Brattle Bookstore in Boston, much to my delight) began the American Laboratory Theater, which would transform The System into The Method.

Boleslavsky lectured at length on the Stanslavski system. He taught that “the actor needs to find the problem for each moment and the action that suits that problem.” He encouraged the use of infinitive verbs to make small objectives more concrete — to anger, to coax, to charm, and so forth. Pieces of action were called “bits,” but because of their thick Russian accents, the word sounded like “beats” and it became the customary term for the breakdown of moments in a script. The acting classes of the imposing Maria Ouspenskaya, who habitually sported a monocle, were known for generating stress. Today she is popularly known as the old gypsy in the 1941 film The Wolf Man, gloriously camping it up against the wooden acting of Lon Chaney Jr.

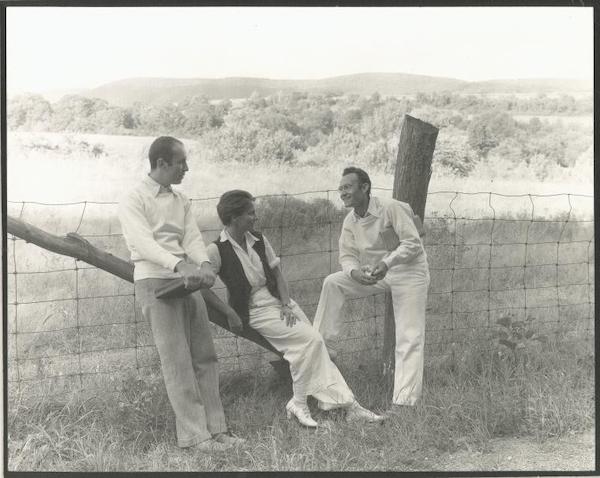

Harold Clurman, Cheryl Crawford, and Lee Strasberg outdoors at Group Theatre in the early ’30s. Photo: New York Public Library

Lee Strasberg attended every performance of the MAT in New York. He and Harold Clurman enrolled in Boleslavsky’s workshops. Together with Bobby Lewis, they founded The Group Theatre, which was active from 1931 to 1940. Group Theatre member John Garfield, tired of being poor, went to Hollywood to earn some decent money. He expected to fail and return to the Group; instead, he became a major film star. Garfield quickly realized that “in the theater you act and in film you react. So it is always safer in movies to underplay.” His performance in 1938’s Four Daughters can be considered the first appearance of Method acting in a Hollywood film.

Method training proved to be perfectly suited for the gaze of the film camera. In 1947, Elia Kazan, Cheryl Crawford, and Bobby Lewis decided to band together to adjust what they had learned about the Method. They wanted to avoid the pressures of ensemble acting and leftist politics, which had made the Group Theater a target of criticism. Their Actors Studio was founded in 1947. Strasberg took over in 1951. The Studio would go on to train some of stage and screen’s finest actors: Montgomery Clift, James Dean, Marlon Brando, Shelley Winters, Lee Remick, Anne Bancroft, Ellen Burstyn, Geraldine Page, Kim Stanle,y and many others.

Brando, while often thought of as the exemplary Method actor, rejected the label. He disliked Strasberg’s inflexibility and overbearing personality. Adler’s coaching and Kazan’s directing nurtured his natural gifts. Kazan brought a collaborative and humanist sensibility in his collaborations with actors. He felt that performers “give you pieces of their lives, which is certainly the ultimate generosity of the artist.” The goal was always to reach what Stanislavski had called “perezhivanie,” or “the power [of] the actual experience genuinely felt by the actor.”

Marlon Brando as Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront.

Butler’s stories about The Method’s effect on American film acting are insightful, particularly when he recounts how actors could become either inspired or angered when they embraced it. Sometimes they would push themselves to unreasonable limits. There is the oft-told story about Laurence Olivier giving some advice to Marathon Man co-star Dustin Hoffman, a Method maven who was exhausting himself searching for the core of his character: “My dear boy, why don’t you just try acting?” Marilyn Monroe, a gifted but deeply insecure performer, kept Strasberg’s daughter Paula as a coach during the shooting of several films, including Some Like It Hot and The Misfits.

Throughout The Method, there are illuminating and useful explanations of a number of Method-based exercises. Some of these training drills will be familiar to anyone who has taken an acting class. The essentials have remained consistent, no matter how notorious the Method has become: what do you want (objective), what is in the way (obstacle), and what will you do to reach your goal (strategy).

Today, accomplished actors like Robert De Niro and Daniel Day-Lewis are more interested in doing research about their roles than delving into their personal lives. There is increasing skepticism about using self-analysis to create character. Furthermore, we are now in the age of ubiquitous self-performance on social media — YouTube, Vimeo, cell phones, TikTok, and Reality TV shows. What constitutes an actor (or even acting) has become fairly amorphous. Today, “real people” are being cast by directors searching for authenticity. Filmmakers like Sean Baker (Tangerine, The Florida Project) and the Safdie Brothers (Uncut Gems, Heaven Knows What) use amateurs to remarkable effect. Meanwhile, many actors are now being required to be physically adept, almost mechanical, when they are asked to perform against green screens and pretend they are “real” environments or battling alien creatures who don’t exist. This evolution of the trade recalls Meyerhold’s notion of actors as übermarionettes.

Karen McDonald in Chaos and Order: Making American Theater, a film I directed about the American Repertory Theater in 2005, has this to say about the nature of acting: “The job of an actor is to be a storyteller. Giorgio Strehler of the Piccolo Teatro di Milano said, ‘I will tell stories any way I can. I’ll tell them on a stage in front of a lot of people. If I didn’t have a stage, I’d stand on the rock. If I didn’t have a rock, I’d sit on the ground. If I couldn’t speak, I’d do it with my hands. If I didn’t have hands, I’d crawl on the ground. The basic thing is that what you’re doing is telling a story.” It turns out that the history of The Method is quite a yarn, and Butler tells it well.

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story, and the short film The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.

Tagged: Isaac Butler, Marlon Brando, The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act