Poetry Review: “Continuous Creation” — A Farewell from a Grand Old Man of Australian Verse

By Jim Kates

Continuous Creation is a deceptively slight book from an incontrovertibly substantial poet.

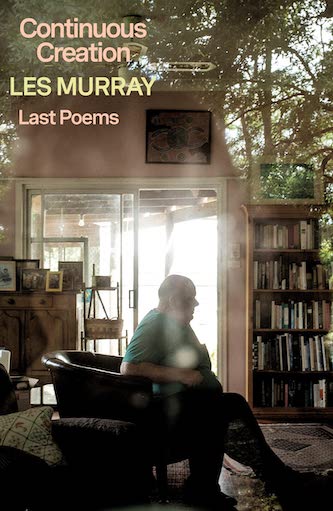

Continuous Creation by Les Murray. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 96 pages, $25.

A significant poet indeed, Les Murray was considered the grand old man of Australian poetry, both rock and fountain. Born in 1938, embroiled in literary contentions and celebrated for his own verse, he also edited an insightful collection of other Australian poets of his generation, Fivefathers: Five Australian Poets of the Pre-Academic Era as well as The Oxford Book of Australian Verse. Murray’s bent was essentially conservative, but this was a rough-hewn Australian conservatism bred in the outback and committed to a broadminded understanding of his country.

A significant poet indeed, Les Murray was considered the grand old man of Australian poetry, both rock and fountain. Born in 1938, embroiled in literary contentions and celebrated for his own verse, he also edited an insightful collection of other Australian poets of his generation, Fivefathers: Five Australian Poets of the Pre-Academic Era as well as The Oxford Book of Australian Verse. Murray’s bent was essentially conservative, but this was a rough-hewn Australian conservatism bred in the outback and committed to a broadminded understanding of his country.

Continuous Creation is a deceptively slight book from this incontrovertibly substantial poet. It may have been inevitable; in the wake of a notable writer’s death, his or her desk gets rifled for unfinished works that can be turned to one kind of profit or another. We’ll all die with our work unfinished, and, according to a “Note on the Text” by his executive editor Jamie Grant, Murray said he’d had “about three-quarters of a new book ready” five months before his life ended on April 29, 2019.

Given all that, Continuous Creation feels unfinished, holding scraps and left-overs, the last seventeen poems (of fifty-three) selected by Grant after the poet’s death. Three of the poems end without any punctuation. Without explanation it’s impossible to know if these are typographical errors or typographical decisions by the poet or his editor. I can’t help wondering a little about how polished Murray had considered some of these drafts now solidified in print. He was not a consistent rhymer, for instance, but he always was a crafty, self-conscious one. In the otherwise evocative “Invention of Pigs,” Murray’s stanzas are rhymed (or not) abbc, deed, fggh, ijki, an inconsistency which looks suspiciously still in process. In content, too, the last stanza feels limply inconclusive, ” . . . where pigs had been legion / only fuzzy white hoofprints crowded / upwind over black, B B B / and none stayed feral in our region.”

As a swan song, or even a cadenza, Continuous Creation hardly satisfies. And it does not serve as the best introduction to Murray’s achievement. (For an introduction, I’d recommend Murray’s own choice, forthrightly titled The Best 100 Poems of Les Murray, published by Black Inc in 2012. Unfortunately, it may be hard to get your hands on it in the Northern Hemisphere.)

This is not to say that the poems themselves are dismissible, even if all the contents of Continuous Creation fail to rise to match Murray’s best. The book will gratify those who want one more collection and a strong echo of the poet’s voice. There are several quietly stunning poems here, along with a few declarative statements that look unlicked into shape, among these several that are starkly observational, like “Metal Birth”:

Big man leaving a small car

turns over, lies across his seat

grips the steering wheel and throws

out a pair of trampling feet

which bend

sleekly to the asphalt. He then

dips his face from under

the dash, up into view,

grinning at the end of an eclipse

and writhes upright, balancing, complete.

Other observations are remarkably keen, like that of the “Australian Pelican,” “rising out of millennia / with its rigged pink sail / climbing to migration,” or delightfully deceptive, as in the haiku “Windfall:”

Kangaroo sleeping

ahead on the road turns out

to be twigs and leaves.

There are more stately poems that take on a vatic tone of voice and a far wider perspective. “Steam Bath World” sweeps in seventeen lines through a cultural atlas of saunas and hot-tubs — “primates born near zero / soak in volcanic water . . . and red-faced humans tip / buckets on scorching rock” to arrive at “that arch Rome never took to. / Sweat’s their archaic soap.”

Beyond the occasional rhyming and a careful control of syntax — even in poems whose exact state of completion is unclear — we can appreciate the care of craft displayed, as in the elegiac quatrain from which the book takes its title. Note how that single adjective “gradual” lifts the poem from banality into agency and action.

We bring nothing into this world

except our gradual ability

to create it, out of all that vanishes

and all that will outlast us.

It is this kind of subtlety that requires our reading and rereading even those poems that seem slight on first perusal. Although Continuous Creation may not be a swan song, it is a lingering farewell to and from a major poet who long graced the homeland of black swans.

J. Kates is a poet, feature journalist and reviewer, literary translator, and the president and co-director of Zephyr Press, a nonprofit press that focuses on contemporary works in translation from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Asia. His latest book is Paper-thin Skin (Zephyr Press), a translation of the Kazakhstani poet Aigerim Tazhi.