Book Review: “Harrow” — The Relentless Dystopia to Come

By Ed Meek

The world of Harrow is a Mad Max dystopia for intellectuals. It’s Bladerunner without the tech.

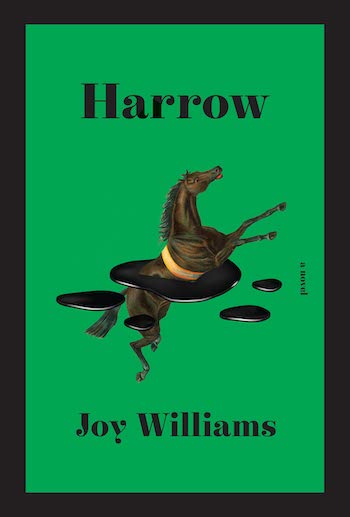

Harrow by Joy Williams. Knopf, 207 pages, $15.99.

“I find words becoming more and more treacherous,” says Kristen, the protagonist of Harrow. This is a novel of a little over 200 pages with not much plot to speak of, yet the author comments with élan on the decline of our era (although the story is set in an indefinite future). Here’s another: “In no other age was there so much pious revulsion with the times.” We do spend a lot of time complaining, don’t we? We may be the second richest country in the world, but we are not a very happy lot. Luckily, we have an industry dedicated to ginning up optimism to help us cope. As Williams puts it, “people who lack all sympathy are feeling better about themselves. The more a person doesn’t care, the freer he becomes.” Wait, that’s not us. That’s the other team she’s talking about — the happy campers at the rallies, right? Not us elite, over-educated liberals.

“I find words becoming more and more treacherous,” says Kristen, the protagonist of Harrow. This is a novel of a little over 200 pages with not much plot to speak of, yet the author comments with élan on the decline of our era (although the story is set in an indefinite future). Here’s another: “In no other age was there so much pious revulsion with the times.” We do spend a lot of time complaining, don’t we? We may be the second richest country in the world, but we are not a very happy lot. Luckily, we have an industry dedicated to ginning up optimism to help us cope. As Williams puts it, “people who lack all sympathy are feeling better about themselves. The more a person doesn’t care, the freer he becomes.” Wait, that’s not us. That’s the other team she’s talking about — the happy campers at the rallies, right? Not us elite, over-educated liberals.

What little narrative momentum there is in Harrow deals with the adventures of Kristen, who is abandoned by her mother and released from a boarding school that closes. She takes a train to a “razed resort,” a motel beside a dying lake to spend some time in a post-apocalyptic world with a few other surviving malcontents. In this version of reality, “The amusement industry has heroically reestablished itself. Disney World has rebooted and is going strong.” As French critic Baudrillard tells us, Disney World is just like the rest of America only more so, a place where amusement-hungry patrons wait in long lines to pay for short-term thrills. Meanwhile, at the resort, the birds are all dead, food is scarce: the wasteland is all too manifest. Inside the motel, “snack machines gleaming in dark alcoves were empty and unplugged.” The world of Harrow is a Mad Max dystopia for intellectuals. It’s Bladerunner without the tech.

In short, the world in the novel is a ruin, a harrowing experience for humans. The entire planet has become a combination of Bangladesh and Route 1A north of Boston. Still, “Denial is now an art, a social grace, a survival tool…” That’s one way to explain the apathetic response of so many Americans to climate change. Williams presents us with the world that is to come given our meager efforts at halting the destruction of nature. Well, what’s the rush? As Joe Manchin would proclaim as he climbs out of his Maserati and onto his yacht. In some ways, Williams might agree: she is convinced it is all over and mankind is toast. Kristen’s comrades would like to overthrow their callous overlords, but they don’t have the power or the energy.

I have to admit that life today can feel like a harrowing experience. “The best lack all conviction, while worst are full of passionate intensity,” as Yeats said in “The Second Coming” over 100 years ago. The lack of perspective on both sides of the political aisle today is unnerving. Shootings, car-jackings, assault, hate crimes, ODs, and suicides are all way up.

Williams, the critically celebrated author of five novels, including The Quick and the Dead, and a number of short story collections, has proven in the past that she can construct a plot with full-fledged characters. But she has not chosen to in this dystopian vision. There’s no point, silly.

A number of years ago I saw two different productions of Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot. Paced slowly, the first was boring. My companion explained to me that the staging had been purposely slow-paced in order to get across the message that life is uneventful without resolution. The second production was quickly paced and came across as a black comedy. Beckett’s poetic despair was there, but this time it was compelling. John Updike once pointed out that, as a writer, “you owe nothing to the truth; you owe everything to your audience.”

What happens when a contemporary novel lacks a plot and characterization? We are left with a collection of observations, at times perceptive, about life as we live it. But Harrow‘s insights are relentlessly negative. Williams would agree with Gore Vidal — human beings are like a virus attacking its host. She may well be correct in her assessment of mankind’s grim prospects — but it doesn’t make for a very good novel.

Ed Meek is the author of High Tide (poems) and Luck (short stories).