Theater Commentary: A Wacky Vision of Violence — “Gary: A Sequel to Titus Andronicus”

By Bill Marx

Finally, a sign that American theater might be facing the world of violence outside of its usual provincial purview.

Gary: A Sequel to Titus Andronicus by Taylor Mac. TCG, 93 pages, $15.95.

At the moment there’s the violence of Russia’s war on Ukraine, from the destruction of cities to the murder of noncombatants, leading to charges of genocide. And there’s the growing turmoil in the civil war in Yemen, one of the Arab world’s poorest countries, which has left an estimated 20.7 million people in need of humanitarian assistance and killed nearly 111,000 people since 2015. The UN says both sides in the civil war — the Saudi-led coalition (supported by the US) and Iranian-backed Houthi rebels — may have committed war crimes. Both combatants deny the allegation. Of course, this is a sampling of present-day global mayhem, but the bloody trend led me to think about the ways in which theater has dramatized mass death over the centuries. It goes without saying that American drama, mired in the domestic for the sake of safety and box office, steers well away from such distasteful doings. Antiwar plays are rarities in the US.

At the moment there’s the violence of Russia’s war on Ukraine, from the destruction of cities to the murder of noncombatants, leading to charges of genocide. And there’s the growing turmoil in the civil war in Yemen, one of the Arab world’s poorest countries, which has left an estimated 20.7 million people in need of humanitarian assistance and killed nearly 111,000 people since 2015. The UN says both sides in the civil war — the Saudi-led coalition (supported by the US) and Iranian-backed Houthi rebels — may have committed war crimes. Both combatants deny the allegation. Of course, this is a sampling of present-day global mayhem, but the bloody trend led me to think about the ways in which theater has dramatized mass death over the centuries. It goes without saying that American drama, mired in the domestic for the sake of safety and box office, steers well away from such distasteful doings. Antiwar plays are rarities in the US.

My feeling is that mainstream theater’s acknowledgment of mass murder — oh-so-fleeting and superficial — is no longer acceptable in the face of what is happening, and what is to come. Is it possible for a playwright to envision a world on stage in which terrorism (in the name of war) eradicates hundreds of thousands of noncombatants, including women and children? Or is this reality better left in silence, for the sake of leaving audiences uplifted rather than shaken up?

My research has not been extensive, but it wasn’t until the theater was forced to deal with the technologically assisted slaughter of World War I that mass death became a presence on stage. Until then, the demise of thousands was alluded to via the eradication of the upper crust. Bread & Puppet Theater’s upcoming production of Aeschylus’s The Persians (at the University of Connecticut on April 23 & 24) sent me back to the play, which is based on the rout of the Persian Empire by the Greek city-states in the naval battle at Salamis. The Persians lost around 400 ships, but the chorus mostly focuses on the demise of the higher ups in the military and how that means the end of the empire. As for Shakespeare, his chorus may, in the preface of Henry V, ask us to believe that “a crookèd figure may/ Attest in little place a million,” but there is not much time spent lamenting mass slaughter in this or his other war plays.

In the early ’30s, poet and actor Antonin Artaud came up with the concept of the Theater of Cruelty. His idea was no doubt influenced by the popularity of Grand Guignol, late-19th-century French entertainments in which bodies were (through stage illusion) sliced and diced and bled for fun. World War I, with its poison gas attacks and butchered civilians, drained this genre of its amusement. WWI underlined the body’s porous fragility, and that led to a radical vision of elemental equality. No matter where you squat in the pecking order, high or low, the bottom line remains: we are bags of blood, shit, and guts. Mechanized, science-assisted warfare underlined collective vulnerability to puncture, poison, and pain. Karl Kraus, in his monumental antiwar satire The Last Days of Mankind, dramatized how this frailty in mind and body (“humanity decomposing”) was exploited by the powerful and their craven enablers in the media. (The epic drama is celebrating its 100th birthday; the text was published in full in 1922.)

It was the unprecedented violence and bloodshed of the 20th century that exposed and targeted the vulnerability of the community rather than the individual. And there were literary artists, such as Artaud, Céline, Beckett, and others whose black comedy honed in on the dark comedy generated by our discomfort with our liquidity, the squishy elemental stuff — shit, gore, spit, etc. — that oozes out of mashed, mangled, and exploded bodies. For them, only grisly humor could reflect the ease with which hundreds of thousands of people could be gutted or gassed. Predictably, this embrace of aggressive satire made little impact on American drama. British playwrights were more receptive — particularly one of my favorites, Peter Barnes, who in his 1985 play Red Noses limned the humane antics of a band of bad jokesters who were charged (by the Catholic Church) to mitigate the plague during the 14th century by keeping the dying laughing. Barnes went ever further into tastelessness with his controversial short play Auschwitz, the second part of an evening entitled Laughter! Here the dramatist lampooned Germany’s bureaucratization of the Holocaust, the revelation of the hideous reality behind the numbers game capped by a farcical conclusion in the title death camp. Barnes used the juxtaposition of humor and horror to underline the savage incomprehensibility of mass death — and to rile up audiences.

Nathan Lane in Gary on Broadway. Photo: Julieta Cervantes

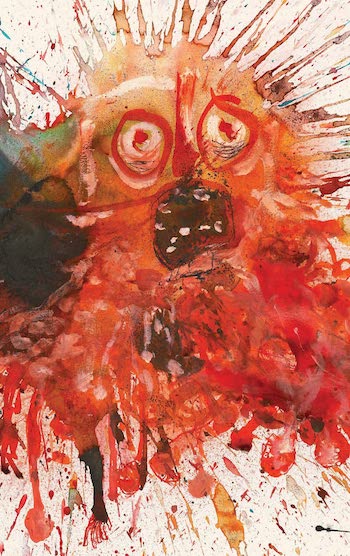

Finally, we have a sign that American theater might be facing the world of violence outside of its usual provincial purview. Taylor Mac’s 2019 charnel house farce Gary: A Sequel to Titus Andronicus is in the tradition of the Theater of Cruelty (with plenty of Barnes’s curdled showbiz antics mixed in). As in Auschwitz and Red Noses, the slaughter of thousands is viewed through a parodic vaudevillian lens. The stage directions detail the rotten, stinking props for the evening’s entertainment: “There is the appearance of at least one thousand corpses on stage (a painted backdrop or other theatrical techniques that give the illusion of one thousand corpses may be used; still there should be at least a few hundred three-dimensional corpses).” The piles of lifeless bodies, bags of blood, shit, and guts, are awaiting a clownish clean-up crew, Gary and Janice, who are charged with tidying up the epic mess — after the coup, the mass slayings, and the fall of Rome — left in the banquet room of General Titus Andronicus. The bladders and intestines of “the corpses” need to be emptied. Heads, arms, and legs must be yanked off. Gary, an inept pigeon juggler, dreams of becoming a court Fool (so he can tell the truth via his jokes and change the world for the better). He begins to manipulate the corpses, whole or in pieces, as fodder for his laugh-a-minute sketches. Janice asks Gary a question to which Artaud and company would no doubt nod yes: “Oh so you’re gonna use the dead for a laugh now too?”

Predictably, the 2019 Broadway production of Gary had 45 previews and only 65 regular performances. Starring Nathan Lane, the show was directed by George C. Wolfe and received seven Tony Award nominations. New York audiences did not find the play funny — and didn’t get that it wasn’t supposed to be. I have been an admirer of Taylor Mac’s plays and reviewed Hir for the Arts Fuse. Gary only reinforces my admiration for his nerve. Unlike Beckett, Barnes, and Céline, the dramatist does not always have the courage of his nihilism. But may his circus of catastrophe inspire other American playwrights to break free of our theater’s hermetically sealed escapism and acknowledge the burgeoning violence and bloodshed of the 21st century.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of the Arts Fuse. For just over four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

A wide-ranging and sharply focused review. Thanks!

Thanks, Kai.

Just speculating how theater might reflect (meditate on?) the growing challenges around us. The use of mass death as a tool for terror is one — as is the global disruptions promised by climate change. Stage companies can try to escape these realities for the sake of “business as usual” — but they will not go away. And the growth of television will continue to marginalize theater … so why not break out of the conventional?