Opera Album Review: Saint-Saëns’s Delightful Skewering of the West’s Fantasies of Japan

By Ralph P. Locke

A major contribution to the recorded repertory, making clear just how effective Saint-Saëns’s The Yellow Princess could be on stage, its nowadays objectionable title repudiated by its varied and nuanced approach to the evocation of the exotic.

Saint-Saëns: La Princesse jaune and Mélodies persanes (in that cycle’s first recording with the composer’s orchestrations).

Judith van Wanroij (Léna), Mathias Vidal (Kornélis); diverse singers (in the song cycle).

Toulouse Capitole Orchestra, cond. Leo Hussain.

Bru Zane 1045—80 minutes.

Click here to purchase or to hear portions of any track.

The Yellow Princess (1872) was Saint-Saëns’s third opera. The title refers to a Japanese woman, or, rather an old painting or print of one that is hanging on a wall in an artist’s studio in the Netherlands in (presumably) the nineteenth century. My first reaction was to think: the work’s title is so offensive that the work should be forgotten and buried. After all, is there ever any excuse for racism?

But then I recalled that I know the work’s overture, seven very fresh and engaging minutes. (I learned it from a 10-inch monophonic LP, which shows you what an old geezer I am.) And I read the new recording’s libretto and, intrigued, started listening. (The recording is the first-ever complete one. The three previous recordings offered the musical numbers, but these made little sense without the connecting scenes in spoken dialogue. The most widely available of them, on Chandos, uses Italian singers who have secure voices but show little connection to the words they are singing.)

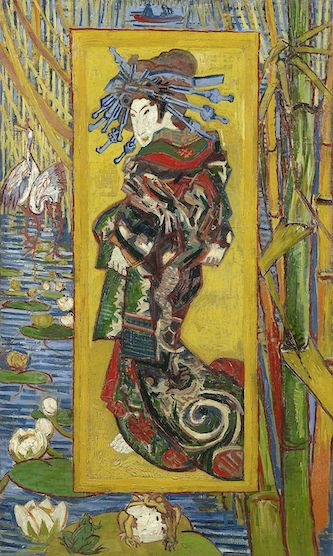

What I found was a work that actually twits the West for its ignorant fantasizing about distant lands. The offensive adjective “yellow” is put in the mouth of Léna, a Dutch woman who paints scenes on pottery, and who realizes that her beloved cousin Kornélis has developed an opium habit and an obsession with the aforementioned old Japanese painting of a young woman. (She speaks the line “disdainfully,” revealing her own cultural narrowness — and of course her understandable annoyance that Kornélis prefers a painted image to her.)

In short, we are not remotely led to think less of Japanese people in this opera. The point is that they have no real existence for the self-obsessed Kornélis. They and their characteristic arched gates and turreted temples are simply visions that he (on the basis of Japanese artworks that he has seen and reading that he has done) conjures up for himself in his drug-induced haze.

Now feeling better about the work, I got to know it more closely and read more about it. My conclusion is that La Princesse jaune is one of the best one-act operas in the repertory (or, at the moment, not in the repertory). It deserves to be staged in an imaginative but closely appropriate manner — not, I hope, “reimagined” when audiences have not yet had the opportunity to get to know it as it is and absorb its complex cultural messages.

La princesse jaune was the third of Saint-Saëns’s twelve operas, but the first to be staged. He also wrote incidental music to plays, even an early film score. We don’t tend to think of Saint-Saëns as a man of the theater, but of course anybody who could write as successful an opera as Samson et Dalila clearly had a feel for situation, character, and drama. (Saint-Saëns had already drafted large parts of Samson when he began to compose La Princesse jaune. But Samson did not get staged until five years after Princesse — in Weimar, translated into German, all thanks to Liszt.)

Singer Judith van Wanroij. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Saint-Saëns’s skill and insight as an opera composer are amply confirmed by The Yellow Princess, a one-act work that was first performed in 1872 at the Opéra-Comique but insufficiently appreciated at the time. Here we have the whole thing (including, as I said, all the spoken dialogue), splendidly realized by two of today’s most gifted young singers of French opera. I previously praised Judith van Wanroij in Gounod’s melodious Le Tribut de Zamora and Mathias Vidal in works by Catel, Spontini, Rameau, Ravel, and, yes, Saint-Saëns (his 1887 opera Proserpine). Here they are as accomplished and natural as ever (she is Dutch, but sure sounds like a native French-speaker to me), and they really cook together in this amusing and touching story of how a Dutch woman, Léna, finally got her cousin, the painter Kornélis (who is also a student of Japanese literature), to give up his cocaine-addled dreams about the Japanese woman depicted in an old painted panel and pay attention to the real woman working side by side with him: Léna herself. Vidal, at a few moments, shows an incipient wobble (slow vibrato). I hope he will choose his roles carefully and also avoid singing in overly large halls, because he is right now one of the opera world’s treasures.

We aren’t sure if the woman in the old painting is a princess and, of course, she isn’t yellow. The phrase is a sarcastic one, spoken in anger by Léna, tired of being ignored. The opera’s message is that exotic dreaming, based on inanimate objects, is hopelessly self-centered. Thus, Japan itself plays next to no role in The Yellow Princess, except for the visuals (a Japanese village magically appears to Kornélis’s, and our, eyes) and several evocative pentatonic passages that let us hear the painter’s wild imaginings and Léna’s attempts at entering into them. The name that he gives the woman in the painting, Ming, of course sounds more Chinese than Japanese, suggesting the painter’s vagueness on cultural matters (another bit of cultural criticism of . . . the West?).

In addition to quasi-East Asian pentatonic writing (often in simple, stiff rhythms), the work features a very different and equally trenchant type of exotic color: pseudo-Middle Eastern. The tenor’s first aria is built of slithery modal melodies (one of which includes the interval of an augmented second) over an open-fifth pedal. I assume that this is meant to remind us that the cocaine that Kornélis takes to fuel his amatory visions comes from the Middle East. The aria derives from a song that Saint-Saëns had composed about the attractions of multiple places in “the Orient,” including the Middle East, but the librettist gave it new words to make it fit the opera better, and the composer altered its ending substantially as well.

The various chunks of exotic music first appear in the wonderful overture, along with other equally attractive music. (Hugh Macdonald’s magnificent study Saint-Saëns and the Stage lists seven recordings made across the decades, plus a 78-rpm two-sider with orchestral selections, presumably containing at least some portion of the overture.) But the whole score is beautifully characterized and crafted.

Van Gogh, “La courtisane (after Eisen),” 1887.

I was repeatedly struck by the rhythmic imagination: phrases extending themselves beyond the 4+4 pattern that was so predictable in the comic-opera repertory at the time. Saint-Saëns himself said (decades later) that the last few numbers were among the best that he ever wrote. Perhaps he was delighted to notice again how symphonic they are, with previous themes now being subject to various developmental procedures that show them in a new light.

Macdonald, in that book on Saint-Saëns’s theatrical works, shows how admirably suited all the music is to the changing glimpses we get of each of the two characters. Or of the two characters plus the imagined Ming: at one point Léna is suddenly seen to be wearing Japanese clothing because we are seeing how she appears to her cousin in the midst of his drug-induced reverie. In other words, it’s a fantastical transformation; Léna has not donned Japanese clothing in order to impersonate Ming.

At the same moment, the painting or print of the Japanese woman, hanging on the wall, magically transforms into a painting of Léna herself, in her usual Dutch clothing. This foreshadows the opera’s denouement, whereby Kornélis finally recognizes that it is Léna whom he has loved all along. (They are said to be cousins, but perhaps a bit distant — there is no anxiety shown about their familial relationship. Perhaps one of them was adopted….)

The CD is filled out with a complete recording of Saint-Saëns’s important song cycle Mélodies persanes. Lovers of French song may know these six masterful numbers from recordings with piano, such as the splendid reading by baritone Tassis Christoyannis (Greek-born, but his French is very good). Christoyannis and tenor Yann Beuron recorded some of them with orchestra as well. It is splendid to have the whole cycle in the composer’s orchestration and with an orchestral prelude and interlude that he composed for a longer, cantata-like version of the cycle. That version, entitled La Nuit persane, omitted one song and added another song and duet, plus passages for chorus (in one case singing an entire song in place of the original solo voice) and, over quiet music, a narrator who is labeled “The Voice of the Dream.” (The full cantata has been recorded once, in Australia: Melba 3011142.)

An essay in the hardback book that accompanies the recording suggests that the cycle, with some songs transposed, could be performed by a single singer. In fact, the version created for this recording does not fully follow Saint-Saëns’s own assignments: the whirling-dervish song that ends the cycle is here sung by a soprano, not (as in La Nuit persane) by a tenor. Since whirling dervishes in Muslim tradition were, I believe, always male, Saint-Saëns’s choice was more plausible, though of course now we tend to believe that a person of any gender should be allowed to participate in any activity. Another possibility is that the soprano here has turned a tenor song into a three-minute trouser role: this dervish is thus a teenaged male.

The six singers of the songs are all native Francophones (though some have names suggesting a family origin elsewhere). They are (in order) baritone Philippe Estèphe, baritone Jérome Boutillier, mezzo Eléonore Pancrazi, tenor Artavazd Sargsyan, soprano Anaïs Constans, and (in the dervish-finale) soprano Axelle Fanyo. (Fanyo’s parents, I have learned, are, respectively, from Togo and the West Indies.) All are very capable, but Pancrazi and Sargsyan stand out as simply marvelous, adding immeasurably to the already-substantial pleasure of hearing these vividly contrasting songs done with the composer’s own glittering, atmospheric orchestrations. One small gripe: I wish the orchestra had been miked just a little more closely, or the voices just a little less prominently. I often wish this when listening to aria discs.

The essays in the small book restrict themselves largely to the opera, giving the songs short shrift. But at least the texts are there, well translated.

All in all, a major contribution to the recorded repertory, making clear just how effective Saint-Saëns’s Yellow Princess could be on the stage nowadays (despite its nowadays objectionable title) and how varied and nuanced his approach to exotic evocation was.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review is a lightly updated version of one that first appeared in American Record Guide, and is included here with that magazine’s kind permission.

Tagged: Bru Zane, La Princesse jaune, Mélodies persanes, Ralph P. Locke, Saint-Saëns

It was interesting to read your comments on the yellow princess. I’m listening to it right now. I’ve always thought that the overture is one of the most perfect pieces of music ever written. I thought so since the first time I heard it 20 years ago. I can understand your concerns about it being racist, but that really wasn’t a lot of what was going on. This is a piece of chinoiserie, Produced by people who didn’t know the people that they were fantasizing about, Or really much about them.. And as you know the story has nothing to do with race as much as it has to do with people.

I also find the music charming and the feeling throughout. I’m listening to that chandos recording, and I believe you The singers are Italian. But they really sound French to me

At any rate, as I say, I think the music for this is wonderful. I would recommend highly for people to listen to it.