Opera Album Review: Donizetti’s Teacher Reveals His Own Operatic Mastery in a World-Premiere Recording of “Elena”

By Ralph P. Locke

This first-rate performance highlights the special attractions of the “half-serious” operatic genre.

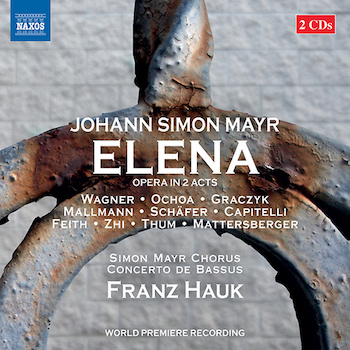

G. S. Mayr’s Elena (1814)

Julia Sophie Wagner (Elena/Riccardo), Mira Graczyk (Paolino/Adolfo), Anna-Doris Capitelli (Anna), Markus Schäfer (Edmondo), Daniel Ochoa (Costantino), Niklas Mallmann (Carlo).

Simon Mayr Chorus and Concerto de Bassus, cond. Franz Hauk.

Naxos 660462-63 [2 CDs] 151 minutes.

To purchase or hear the beginning of each track, click here.

Another semiseria opera! I am getting fond of this genre, even though our opera houses often don’t know what to do with it. Directors, singers, and audiences can be puzzled by the often grim and tortuous events in the course of the opera, which then all seem to be forgotten via a happy ending. There can also be some startling shifts of tone along the way, thanks to a comic character or two. Still, Bellini’s La sonnambula has made a place for itself, and theatergoers and home-listeners are getting to know Rossini’s La gazza ladra and Matilde di Shabran and can even become immensely fond of them, especially when the singers are first-rate. (See my review of Matilde.)

Another semiseria opera! I am getting fond of this genre, even though our opera houses often don’t know what to do with it. Directors, singers, and audiences can be puzzled by the often grim and tortuous events in the course of the opera, which then all seem to be forgotten via a happy ending. There can also be some startling shifts of tone along the way, thanks to a comic character or two. Still, Bellini’s La sonnambula has made a place for itself, and theatergoers and home-listeners are getting to know Rossini’s La gazza ladra and Matilde di Shabran and can even become immensely fond of them, especially when the singers are first-rate. (See my review of Matilde.)

Here’s a semiseria by Giovanni Simone Mayr, an important opera composer from Bavaria (born Johann Simon Mayr) who made his career in Italy and is best known as the teacher and mentor of Gaetano Donizetti. The recording, the work’s first-ever, offers a bushel-basket of delights.

I have praised Mayr’s operas in previous reviews: Medea in Corinto, Telemaco, and Le due duchesse. Elena (sometimes known as Elena e Costantino [or, at times, Constantino]) fully satisfies my expectations. Here, again, we encounter a master of the operatic craft, fully capable of spinning out an aria, duet, or larger ensemble with singable vocal lines and fresh orchestral colors. Mayr captures the shifting tones of the plot more than capably, reminding us that Rossini did not come out of nowhere: there were a host of highly skilled Italian and French opera composers in the generation before him (and, in the case of Mayr, overlapping with him), including, to mention three other names, Cherubini, Paër, and Méhul.

The libretto, based on one that Méhul set in French eleven years earlier (Héléna), uses a variant of the “rescue” plot that opera lovers today (and record collectors) may know from Grétry’s Raoul Barbe-Bleue and Beethoven’s Fidelio.

Costantino, the duke of Arles, has been deposed, and his wife Elena and their son Paolino have had to flee. The latter two end up at the large farm owned by Carlo (a comical role originally sung in Neapolitan). The usurper has died, but his son Edmondo, long searching for Costantino and family, finally ends up at Carlo’s farm. At Edmondo’s insistence, the local governor arrests the three refugees and brings them before court. But, in time, Edmondo “abandon[s] his loyalty to his dead father and reveals the crime and Costantino’s innocence.” Much delight on stage, and praise for Edmondo’s having done the right thing.

The music is delightful from beginning to end. The overture, which traverses a number of styles (including a rustic opening), would make a splendid offering for any smallish but well-trained high-school or college orchestra. Most of the arias and duets (and one very effective trio, for the soprano and the two low-voiced males: Elena, Costantino, and farmer Carlo) are on the brief side, though often wittily colored by commentary from one or two wind players. The disguised mother and son (Elena/Riccardo and Paolino/Adolfo) get a duet-romance that is mostly in folk style, similar to the sad song that Rossini’s Cenerentola sings to herself sitting on the hearth, but with a compact florid cabaletta. A relatively elaborate sextet in Act 2 was much praised when the opera reached Milan’s La Scala. The French novelist and essayist Stendhal reported that people were making the long trip to Milan to hear the opera, which he called a “work of genius.” (Goethe read this and asked his composer-friend Zelter to get a copy of the score for him.) The work ends with a jovial “vaudeville finale” (with brief solos by each major character), akin to the ones that end Mozart’s Abduction (decades earlier) and Rossini’s Barber (two years later).

The version of the opera here uses the recitatives that Mayr (or others — the booklet is not quite clear) provided for productions outside of Naples, e.g., in Florence and Milan. So we get as much music as possible, and don’t have to bear with foreign singers trying to speak quick Italian (and Neapolitan) dialogue.

Soprano Julie Sophie Wagner brings her glamorous aural presence to this recording.

The recording was made by the team that has brought more Mayr to market than all others combined. The conductor, Franz Hauk, knows Mayr’s style inside-out, and his singers include some masterful ones: soprano Julie Sophie Wagner (whose glamorous aural presence I enjoyed in an opera by twentieth-century Swiss composer Richard Flury), the much-recorded Markus Schäfer (still sounding in fine shape at age 57), and Daniel Ochoa (who has been popping up, pleasingly, on numerous recordings over the past decade and who here grabs the ear at his first appearance, as the rightful duke in hiding). Niklas Mallmann, as the farm-owner, is not in the exalted class of those three, but his voice has the same smoothness here that I praised in a Mayr’s Le due duchesse, and, unlike so many bass-baritones these days, it is not slender at the low end of his range. Still, I wish the role had been given to a native Italian-speaker who could bring out its comic potential. (For examples of this see my reviews of operas by de Giosa and Bellini.) Even the small roles are taken by singers with healthy and clear — if often somewhat thin — voices and who understand the dramatic import of the text. Tenor Fang Zhi (as the Governor) has a meltingly lovely sound, but his coloratura is imprecise, and he lacks fullness in the role’s lowest notes.

Tenor Markus Schäfer.

The smallish orchestra is extremely vivid. The string instruments play incisively (yet not irritatingly) and the winds display their individual colors, such as the prominent, very outdoors-y clarinet and horns and the decisively military trumpet. Conductor Hauk reveals a marvelously apt feel for pacing. I presume he is also the capable but modest-sounding harpsichordist accompanying the recitatives, along with an unnamed cellist.

The sound, as captured in the high-ceilinged concert hall in Neuburg an der Donau (in Bavaria), nicely balances clarity and resonant warmth. This lavishly decorated Baroque-era hall is located in a former Jesuit school; it seats 220, a near-ideal size for a performance with a very small orchestra and (mostly) light voices.

The libretto, available online, is in Italian with German translation but no English. Memo to Franz Hauk and Naxos: Please think of the many potential purchasers, and “streaming” listeners, who live outside the German-speaking lands!

And a warning to the user: Two of the characters are traveling incognito for much of the opera. Thus, when lines are printed in the libretto as being sung by “Riccardo” or “Adolfo,” you have to remember that the actual character is, respectively, Elena or Paolino. But perhaps this consistent omission adds to the fun and reminds us that we are hearing a work of theater, where things (as in life, as well) are not always what they seem.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.