Visual Arts Book Review: “Florine Stettheimer: A Biography” — One of American Art’s Greatest Enigmas

By Peter Walsh

The volume’s overarching goal is to restore Florine Stettheimer to what the biographer sees as her rightful reputation as one of the great American artists of the 20th century.

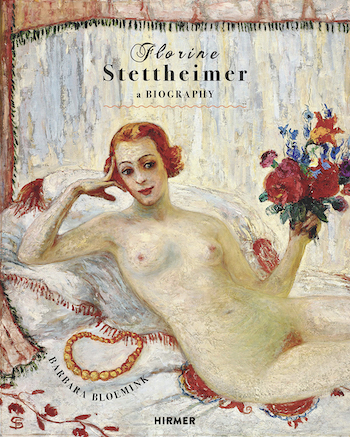

Florine Stettheimer: A Biography by Barbara Bloemink. Hirmer Publishing/ University of Chicago Press, 560 pages, (hardcover) $30.

In Florine Stettheimer: A Biography art historian Barbara Bloemink sweeps, via the grand gesture of a scholarly argument, almost everything that has been written about her subject onto the floor. Stettheimer’s reputation as an “outsider” artist, as a kind of self-taught, upper class Grandma Moses who only showed her paintings to friends and family in her secluded Manhattan apartment is utterly false — a kind of artistic libel.

Bloemink directs her particular ire against Stettheimer’s first, and only previous, biographer, the film critic Parker Tyler, whose book was commissioned by the Stettheimer’s family lawyer, Joseph Solomon, some fifteen years after the artist’s death. In Tyler’s narrative, Stettheimer is a fragile, timid, eccentric, untrained, “naive,” painter who, when her first solo exhibition at New York’s prestigious Knoedler Gallery in 1916 failed to sell, refused to exhibit her work publicly for the rest of her life.

All of this, Bloemink insists, is wrong. Tyler did, in his book, admitt he barely knew Stettheimer and “made up” or exaggerated most of what he wrote. Bloemink’s contempt for Tyler’s travesty is so complete that, by the end of her own book, she describes it as “the first” Stettheimer biography.

Tyler’s unfortunately very influential presentation is easily dismantled. Far from refusing to exhibit after her 1916 Knoedler show, Stettheimer regularly exhibited her work, in New York, Paris, and numerous other places, often in several group exhibitions in a year and frequently by invitation. She was in the unjuried show that included her friend Marcel Duchamp’s scandalous Fountain — his first ready-made: a urinal signed “R. Mutt.” She was represented in the 1929 Arts Council’s exhibition, “One Hundred Important Paintings by Living American Artists.” She was in the first Whitney Biennial in 1932. She was in the 1939 Museum of Modern Art exhibition “Art in Our Time” (an epic survey of modern art in which she was one of only three women included. The other two were Georgia O’Keeffe and Mary Cassatt) and in four other MoMA-organized exhibitions in the ’30s and 40s, including “Three Centuries of American Art,” shown at the Jeu de Paume in Paris in 1938. She exhibited in Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Institute, at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia, at the Salon d’Automne in Paris, at the Worcester Art Museum in Worcester, Mass in 1920, at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford in 1935 and 1940, and at numerous group shows at commercial galleries. In 1946, after her death, the Museum Modern Art mounted a major retrospective exhibition of her work. Duchamp served as curator

Florine Stettheimer, Portrait of Myself, 1923.

Despite Tyler’s easily-refuted untruths, his image of Stettheimer stuck, repeated by nearly every writer about her career ever since. He presented an easy explanation for Stettheimer’s art, which otherwise took some effort to place. Stettheimer is perhaps the most enigmatic artist in the history of American art. Although they show knowledge of almost every art movement of the early 20th century, her paintings are not like anything else.

Bloemink, who has served as a director and curator at five art museums as well as co-curator of the Whitney Museum’s 1995 Stettheimer retrospective, sets out to rebuild the artist’s life and reputation from the ground up. Far from being timid, she says, Stettheimer was a progressive feminist whose unconventional canvases and bohemian salons often shocked family members and their social circles. She raises some interesting questions about how artistic reputations are built and maintained, about the development of American art in the 20th-century, about social class, gender roles, and the influence of gender on aesthetics.

Stettheimer was probably less deserving of labels like “naive” or “untrained’ than any other American artist of her generation. She came from a wealthy German-American-Jewish family (with some Dutch Reform ancestry on her mother’s side) distinguished for its connections to the leading Jewish dynasties of New York City, including the Guggenheims and Seligmans, and for its strong and accomplished women. Born in 1871 in Rochester, NY, where her father’s family owned several successful businesses, Florine lost her father at age seven when, after some business reversals, he abandoned his wife and five children and disappeared (not especially unusual in 19th-century America. Frank Lloyd Wright’s father did the same thing). A family legend has it that he emigrated to Australia, but Bloemink has found no trace of him there.

After returning to her native New York to be near her very wealthy relatives, Florine’s mother, Rosetta (née Walter) and her three unmarried daughters — Florine, the middle sister, Carrie (Caroline), the eldest, and the youngest Ettie (Henrietta) — took up a lifestyle out of Edith Wharton, Dividing their time between stints in New York and long, wandering sojourns in Europe, they lived in hotels and family or rented apartments in places like Stuttgart, Munich, Berlin, and Paris.

Florine took full advantage of these years by preparing for her chosen career as an artist. Although they paid the bills for lessons and studio space, her family never took her art-making seriously. As a pastime it was fine, but in their social class a career as a professional artist was not appropriate for a woman.

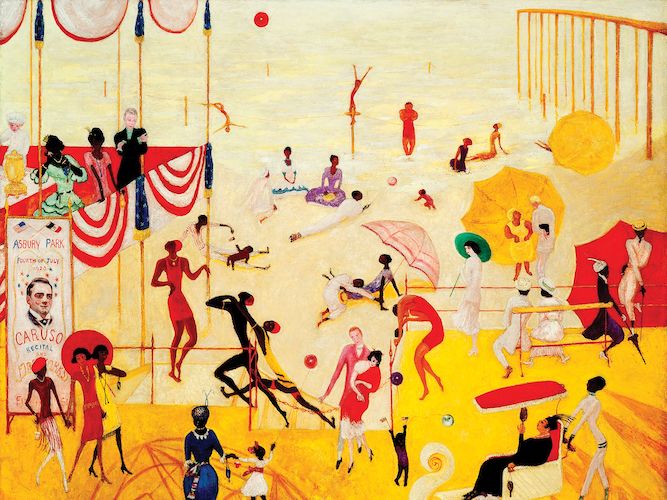

Asbury Park South, Florine Stettheimer, 1920. Collection of Halley K. Harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld, New York, New York.

This peripatetic life lasted nearly four decades. Like Picasso, ten years her Junior, Stettheimer mastered academic drafting as a teenager and went on to experiment with various modernist styles. Matisse was an important early influence as was a brief revival of rococo taste in France at the beginning of the new century. Florine read voraciously about art, so much so her sister claimed she had read “everything.” She completed a four-year course of study at New York’s celebrated Art Students League and studied and worked whenever her family’s demanding domestic schedule allowed. She haunted European museums, keeping up with the latest contemporary trends as well as with the great European historical schools at a particularly fertile and adventurous time for both contemporary art and art scholarship.

In Paris, in the early years of the 20th century, Stettheimer was exposed to the latest work of Monet, Matisse, and the Cubists, as well as the flourishing gallery scene and booming international art market, flooded with wealthy Americans eager to acquire some continental polish. She attended performances of Serge Diaghilev’s culture-disrupting Ballets Russes and saw the young Vaslav Nijinsky perform his “L’Apres-midi d’un Faune,” which shocked the city with its sexual imagery. Florine was moved to design her own ballet, never realized, including costumes, sets, and a libretto based on the Orpheus legend as updated in the riotous Paris art student annual celebration, the Four Arts Ball (her theatrical ambitions were later realized in her designs for the seminal 1921 Gertrude Stein-Virgil Thomson opera, Four Saints in Three Acts). Bloemink describes the Ballets Russes as “[b]y far the greatest influence on Stettheimer’s mature painting style.”

The outbreak of the First World War temporarily stranded the Stettheimer women in Switzerland; they soon departed for New York never to return. Florine was now in her mid-forties, and about to come into her own. She painted a nude self portrait (on the cover of the book’s dust jacket and in a two-page spread inside) that was “inappropriate” to the norms of the time in just about every possible way.

In an inherited brownstone on West Seventy-Sixth Street, in the “Jewish Fifth Avenue” of the Upper West Side of Manhattan, around a rented summer mansion on the Hudson, and later from a sprawling fourteen-room apartment at Alwyn Court, on the corner of Fifty-Eighth Street and Seventh Avenue, a block south of Central Park, a building “alive with crawling salamanders and plumb putti,” the Stettheimer sisters established their famous salon, attended by ex-pat and American artists like Duchamp and Elie Nadelmann, Georgia O’Keeffe and the Stieglitz circle, famous novelists and popular playwrights. Perhaps most notoriously for their relations, they welcomed those who practiced “alternative lifestyles” to be themselves, long before such things were tolerated in other sectors of polite society. All was funded by a substantial family trust fund that freed the Stettheimer women from any financial concerns for the rest of their lives.

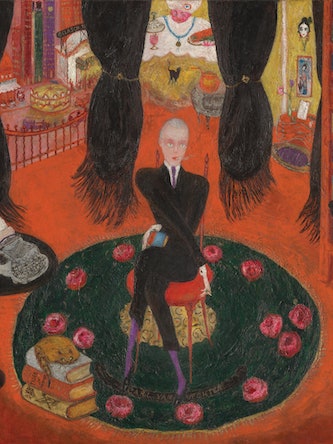

Florine Stettheimer, Portrait of Carl Van Vechten, 1922. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

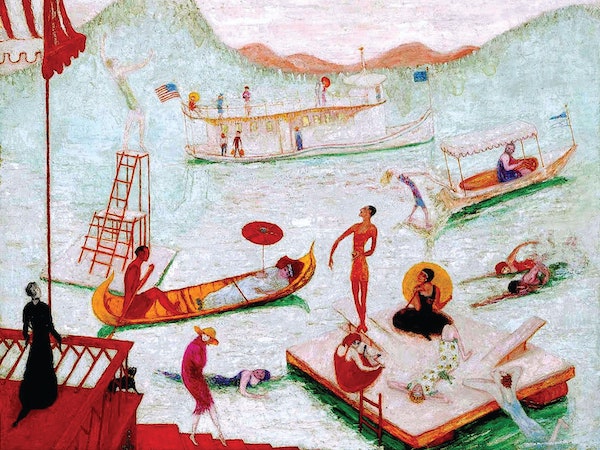

Bloemink identifies 1916 as “the pivotal year” in the development of Stettheimer’s mature manner, described as a “uniquely feminine, subversive style.” Painted on canvases carefully built up with layers of white, Stettheimer painted in brilliant, pure colors, often brushed on right out of their tubes. She painted flower still lives, portraits of friends and family, and her best-known works, large figural paintings that represented social gatherings, locations, allegorical subjects or some combination of all three. These pictures, Bloemink explains, were inspired partly by theater, opera, and Ballets Russes productions, particularly the latter’s radical costume designs. Stettheimer’s compositions and figures were partly based on Persian miniatures, reconceived on a gigantic scale, with high horizons, flat, sinuous figures, and a lack of an obvious focus. The effect is visually fascinating, charming, and mysterious. Persian miniatures were created as book illustrations, so they always have a text. Stettheimer’s paintings require explanations to be fully understood and appreciated.

These works are theatrical, sometimes set between painted curtains, and often narrative. They can show the same figure in different poses as well as events in different parts of the painting, a practice exploited by painters of the early Renaissance to narrate the lives of the saints. Many of the sinuous, animated figures were portraits of family and friends, and the pictures could narrate actual events in Florine’s life. She designed unique frames for her paintings and conceived, like the Ballets Russes, a complete environment for them in the elaborate decor of her studio and home with its furniture that Stettheimer also designed.

Bloemink, who holds a Ph.D. from Yale, has devoted a considerable chunk of her professional career to Stettheimer. She is currently at work on the artist’s catalogue raisonné. She makes ample use of primary sources, particularly Florine’s diaries and her often sardonic poetry. The biographer’s trenchant arguments, nearly always convincing, analyze Stettheimer’s feminism, her uniquely feminine style, her radical social attitudes, and her adventurous approach to art-making. Bloemink patiently deciphers the sources, characters, and events that shaped Stettheimer’s major works, with savvy attention to their social and political significance. Her book, beautifully produced in Germany, has all the illustrations, in black and white and color, one could reasonably ask for.

The book has two main flaws, neither of which is really Bloemink’s fault. One is Stettheimer’s highly privileged social class, which kept her from the financial, social, and aspirational challenges that make up the meat of many biographies of creative people. It sometimes seems that the greatest dramas Stettheimer ever faced were dealing with hotel food and the endless social obligations of being part of a large, upper class family, which cut down on her time in the studio. Her privilege seems particularly remote in this time when the focus of so much contemporary art is on social and economic justice, diversity, and unheard voices.

The second flaw aids and abets the first. Following her older sister’s death in 1944, Ettie Stettheimer went through Florine’s diaries and papers, destroying anything that seemed “inappropriate” to her. Just when one of Florine’s relationships with a young man begin to grow intense and interesting, for example, Bloemink discovers that critical pages have been cut out of Florine’s diary, rendering the climax of the affair a loss to history. As a result, Stettheimer probably comes across as a bit more stuffy, detached from the trials of life, and querulous than she was in real life.

Bloemink’s overarching goal is to restore Stettheimer to what she sees as Florine’s rightful reputation as one of the great American artists of the 20th century and a leading modernist, a reputation she seems to have had in life in at least some important quarters, though she has never really been recognized as such by a wider public. The biographer faces several formidable hurdles. As a self-consciously feminist and feminine artist, Stettheimer swims against the main tides of American art, which have always turned in a distinctly masculine direction. The popular American painting styles have used angular lines, bold gestures, dark or saturated pigments, and gritty or sardonic subject matter — all things antithetical to Stettheimer’s style. There are no American Bouchers or Watteaus. Although appreciated during her lifetime, Stettheimer died just as the most dramatically masculine style of all, Abstract Expressionism, came to represent American art on an international stage. Even Florine’s fellow women artists, like Georgia O’Keeffe and Louise Nevelson, dressed in somber, masculine styles and denied any expressly feminine inspiration for their work.

At her death, most of Florine’s major works, which she couldn’t bear to part with,remained in her possession. She left them to her sisters, with the hope that they would be donated to “a [single] museum,” a legacy protection move used by other artists, including Edward Hopper, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Andy Warhol, who either left their entire artistic estate to a single institution or to a namesake museum dedicated to preserving, studying, and making the works known to a broader public.

Florine Stettheimer, Lake Placid, 1919. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of Miss Ettie Stettheimer.

he redoubtable Stettheimer family attorney, Joseph Solomon, evidently tried to place Florine’s artistic estate in one place, but found no takers, though many museums and universities were more than happy to take smaller parts of it. The process of distribution took decades, until well past the death of all the Stettheimer siblings. Florine’s legacy was scattered all over the country. A cache of papers went to Yale, the ballet designs and some important family portraits went to MoMA, a group of paintings and her specially designed furniture went to Columbia University, the important Cathedral series went to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Single paintings went to many institutions, including collections at Stanford, Harvard, the Boston Athenaeum, the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, and many other institutions, where they remain today..

Once in their new homes, these works were not always appreciated or well looked after. Although Solomon gave a significant sum from Ettie’s estate to Columbia University to have its Stettheimer paintings permanently installed in a special room on campus, they never were. Columbia transferred Florine’s furniture to its theater prop collection, where it was repainted and recycled over many campus productions until it disappeared. For decades, the Met consigned the Cathedrals of Art paintings to basement storage, where a delighted Andy Warhol later saw them. They were finally put on permanent view in the ’90s, as interest in displaying the work of female artists grew.

In her “Epilogue,” Bloemark lists a series of exhibitions, including ones organized by Linda Nochlin, MoMA, and her own Whitney retrospective, that have helped revive and correct Stettheimer’s reputation. Still, with so many works owned as “one-offs” by many museums, Stettheimer’s paintings, even when they are on public view, typically lack the contexts that, more than the work of almost any other modern painter, make them comprehensible. Too often, these strange works come across as startling and bewildering — exotic beasts that seem to have wandered into the wrong menagerie. After the exhibitions of women artists, Bloemink writes, the Stettehimers too often go back into storage. Despite her true role in American culture, it is still too easy to think of Stettheimer as an “outsider,” despite her many lasting connections to American art, its museum and artistic communities.

In the very last sentence of her book, Bloemink writes “[a]t the 150th anniversary of Florine Stettheimer’s birth, it is time to fully acknowledge her as one of the most innovative and significant artists of the twentieth century, as well as being one of the most relevant for the first decades of the twenty-first.” Let’s hope the art world is listening.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. As an art historian and media scholar, he has lectured in Boston, New York, Chicago, Toronto, San Francisco, London, and Milan, among other cities, and has presented papers at MIT eight times. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in anthologies. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 80 projects, including theater, national television, and such award-winning films as Spotlight, The Second Life, and Brute Sanity. He is a graduate of Oberlin College and Harvard University.

Tagged: Florine Stettheimer, Florine Stettheimer: A Biography

Thank you for this review.

I found it truly exciting that she is finally getting a proper analysis of her original artist creations.

I agree that when seen as one ovs is unfair

Although we could probably say the same for other one ovs, say by Hartley or Dove.

Congratulations on your review

Sylvia 81 year old artist in Ottawa ,Canada

Exhibited

Created some really excellent work , basically unrecognized,

Happy Spring in 12 days.

I just finished this book and it is absolutely SUMPTUOUS. Everything about it is sensual: the pages are printed on thick smooth paper; the chapter openings are pink ovals with scalloped edges (Stettheimer’s favorite color/motif; the paintings are as rich as any such reproductions can be.

The prose is a delight as well–straightforward and clear, Stettheimer is explained as part of a particular period and movements. Author Barbara Bloemink clearly admires Stetthiemer’s work without being blind to her other personality traits. ( I hesitate to say her caustic personality, for, as Bloemink points out, women of any stature in any position of notoriety are ALWAYS expected to be “warm and kind and. . .”).

I especially appreciated the author’s detailed commentary on each painting. Stettheimer’s work is a highly detailed documentary, and, while it can be enjoyed just for its exuberance and color, it is so much more meaningful when you know the how, what, and why of the details.

I’m so happy to see this excellent review on the book, and hope others read it–and the book–as well. The reproductions of the paintings are well worth the price of the book. I only wish I could see them in “real size.”

Thank you!!! Your liking my book is so appreciated as I’ve spent 25 years trying to ensure Stettheimer is properly recognized for the innovative terrific artist she was!