Arts Remembrance: Jack Kerouac at 100 — A Conversation with John Sampas

By David Daniel

Jack Kerouac would have turned 100 on March 12. Here’s a 2014 conversation about the writer with his literary executor, the late John Sampas.

Editor’s Note: The estate of writer Jack Kerouac has been a matter of lengthy legal dispute, with claims and counterclaims about the validity of signatures on wills. In some minds it has never satisfactorily been resolved.

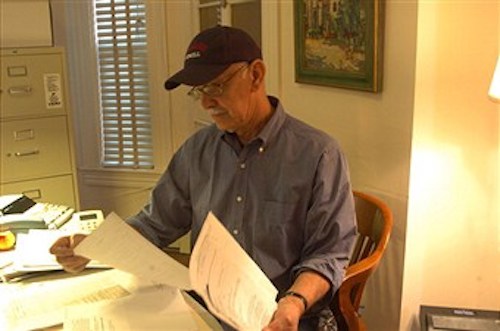

The late John Sampus. Photo: Beatdom.

I first met John Sampas in 2003 when I was appointed as the Jack Kerouac Visiting Writer in Residence at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. The final step for approval for the residency was to have dinner with Mr. Sampas. I went with some misgiving, owing to things I’d read about his selling off parts of the Kerouac estate (the trench coat to Johnny Depp story) and making scholarly access to the writer’s work difficult. By evening’s end, however, I was won over by Sampas’s transparent enthusiasm for Kerouac’s artistic achievements and his devotion to keeping the writer’s legacy alive. A decade later I sat down with Mr. Sampas to talk about his role as Kerouac’s literary executor. The interview was conducted in his home in Lowell, on February 18, 2014. Sampas died in 2017.

Snow is beginning to fall as I park in front of number two Stevens Street, a tall rust-brown Victorian, not far from the University of Massachusetts Lowell campus. The house is the one where Sampas, the youngest child of a large Greek immigrant family, was raised. I am greeted by John, who offers a handshake, and by his dog, an aged Black Lab/Great Dane mix. “That’s Henry,” Sampas says. “Adopted from the pound. Jack would’ve liked him, but cats were his favorites.”

The house’s interior is warm, not fancy. The rooms I see are crowded with shelves, which hold a vast collection of Beat books, including foreign language editions of Kerouac’s works, and volumes on art and jazz. Old paintings adorn the walls. I notice filing cabinets: three in the foyer as I come in, another two in a side room, three more in the room where we will talk. Sampas has a round table set up and a soft green leather chair for me. He offers tea. Classical music plays softly from a radio — 99.5 WCRB in Boston.

Sampas sits opposite and we start. He is a soft-spoken man of about 80, with a twinkle in his eyes when he talks. As the conversation proceeds, I realize that he, as Kerouac was, is loath to say a bad word about anyone. Many names come up: Kerouac’s boyhood buddies, later friends and acquaintances, literary folk. Wanting to give some focus to the discussion I say, “You’re the keeper of the Kerouac flame. What is the role and function of a literary executor?”

“It’s decision-making, power of estate. This involves copyright and intellectual property rights — people requesting permissions to quote from work. Film, translation. Analyzing royalty statements, contracts . . .” He rattles it off; it’s a question he’s been asked a lot. “There are fees to agents, lawyers. There’s a lot of interest in Jack, as you know. One of the big tasks was determining where his papers should be housed and curated. Jack was compulsive about saving things. There was an archive in Lowell, a locked room in a house on Wilder Street which had his materials.”

He explains that agent Andrew Wiley was after him for years hoping to represent Kerouac’s work, but Sampas stayed with the Sterling Lord Literistic, though with a younger assistant rather than Lord himself (who was Kerouac’s agent), “only because I felt Lord hadn’t done enough to maximize earnings for Jack.” Sampas mentions, for instance, that Lord was approached about a film of On the Road many years before and the filmmaker was willing to pay $125K, “but Lord told Jack to hold out for more, and the offer went away.” [Note: After Sampas died, his nephew Jim Sampas and adopted son John Shen-Sampas moved the Kerouac account from Lord’s firm to Wiley’s.]

Jacket worn by Jack Kerouac. Displayed at The Beat Museum in San Francisco, California.

According to Sampas, when Kerouac died in 1969, his mother Gabrielle and wife Stella were living “mostly on Social Security and some royalties — about thirty thousand a year, from On the Road. Gabrielle and Jan Kerouac were his co-heirs.”

At the time of Kerouac’s death, OTR had been translated into half a dozen languages. Forty-five years later, by Sampas’s count, the number of languages was close to fifty.

Kerouac left his estate — at the time, worth very little — to his mother Gabrielle. When she died (1973 at 78), her will directed that the estate go to Kerouac’s widow, Stella. Upon her death (1990 at 71), rights went to the Sampas’ siblings. John took over as executor in 1991, chosen by his siblings to represent the estate.

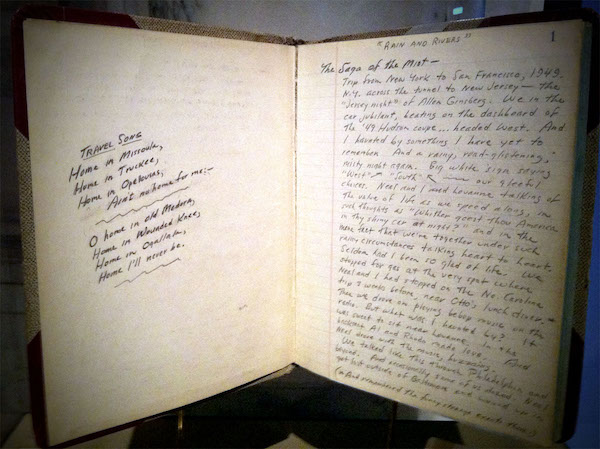

“I began the task of going through what was there,” he says. “There’s a lot. I started with the notebooks. There were more than seventy notebooks, journals, diaries. I’d take one to bed with me each night. Curling up with Jack, so to speak. Remember, I was much younger than Jack. He was friends with my older brothers. Sebastian and Jack were best friends. I didn’t know him all that well when I was growing up. So, after Stella died, I began reading the notebooks to learn more about the man who’d been my older brother’s friend and my sister’s husband.”

Sampas took the assignment seriously. He undertook going through the archive to see what was there. He had the contents of the locked room on Wilder St. transferred to a vault at a downtown bank.

“I was also collecting everything of Kerouac’s that I could, wherever it was, gathering up materials relating to Jack. I got the correspondence between Viking Press and Jack. I got original manuscript copies of many of Jack’s books that Sterling Lord had in various drawers in his office in New York. Stella and Jan [Kerouac, Jack’s daughter] hadn’t renewed rights on certain things and Lord didn’t either, so some of the stuff ended up in public domain.”

Sampas’ next major concern was finding a permanent home for the archives. He had also begun to sell manuscripts to the New York Public Library, and that seemed a likely place for everything. “UCal Berkeley and the University of Texas were also interested, but,” Sampas laughs, “New York is the center of the world. They showed up at the bank with a truck and took it away. I was amused that the bankers never realized what had been stored in their vault. Now they take pride in it.”

Sampas hired writer Paul Marion to do the initial cataloguing of Jack’s papers. Marion remembers Sampas taking him around one day to several banks to show him manuscripts in safe deposit boxes. He describes being “totally blown away seeing scroll manuscripts and bound typescripts in the metal bank boxes.” Marion told me recently, “In 1991, when I was brought on board to catalogue and generally assist John with Estate matters, I told someone that seeing the manuscripts in the bank safe-deposit boxes was like opening up the top of Kerouac’s skull and looking inside to see all the writing in there.”

Around 2000, New York Public Library became the home for the bulk of the Kerouac Archives.

“The editor for Jack’s stuff at Viking was David Stanford, from about 1991-98. Then Paul Slovak became the editor and got some more stuff published. Atop an Underwood [1999, edited and intro’d by Paul Marion] was with Viking.

“After a point, however, Viking didn’t want to do any more,” Sampas says, “so I went somewhere else. Actually, City Lights was the first to publish a posthumous book [Pomes All Sizes, in 1992]. Most recently it’s Da Capo — The Sea is My Brother [2011; intro by Dawn Ward] and next up is The Haunted Life [which appeared later in 2014, Ed. by Todd Tietchen]. The Library of America published Collected Poems [Ed. By Marilene Phipps-Kettlewell, 2012] and there’s a short manuscript titled ‘I Wish I Were You’ which may come out. It’s Jack’s solo version of the Lucien Carr/ David Kammerer case, which he and Burroughs had dealt with in The Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks.”

At the time of Kerouac’s death, he had published eighteen books. Since then, beginning in 1971, more than 25 more additional works have been published, most of which Sampas shepherded through the editorial process. He also got poems by his brother Sebastian, who died during World War II, published.

Sampas says that he has regular, amiable dealings with James Grauerholz, William Burroughs’s executor, and Peter Hale and Bob Rosenthal, who oversee Allen Ginsberg’s estate.

In October 1993 I had spent several hours talking with Kerouac biographer and scholar Gerald Nicosia (Memory Babe) and biographer Brad Parker, so I was aware of the conflicting claims about the Kerouac estate. I knew that 2004 and 2009 Florida court rulings had left the matter muddled. When I mention this, Sampas firmly shakes his head, obviously still galled by all of that, but he doesn’t get over-reactive. “I’ve avoided legal squabbles. I get sued sometimes, but I don’t sue. I try to resolve things equably.”

Sampas has meticulous records and files, duplications of what is in the formal archives in New York. This explains the numerous filing cabinets visible from where we sit. He says the system of organization owes in large part to Kerouac’s own almost obsessive record-keeping, list-making, filling of notebooks and journals, and using carbon paper whenever he typed a letter. “And his correspondence was voluminous!” Sampas emphasizes.

A page from one of Jack Kerouac’s notebooks. Photo: Beatdom.

In the course of our conversation, Sampas is able to access materials he wants to show me. With something like the glee of a child demonstrating mastery of a mechanical toy, he makes mention of an obscure New York literary magazine from the early ’50s containing work by Kerouac and LeRoi Jones (before he became Amiri Baraka) and, voila!, opens a file drawer and produces it. He does this several times, presenting materials to document a point. He shows me a copy of the Lowell police arrest log dated August 12, 1968, with Kerouac’s name and the offense “drunk”; under “occupation” the booking officer had written “writer.”

Sampas says that when Kerouac was in Lowell in 1967 and ’68, living on Sanders Avenue in the Highlands, he hung out with Tony Sampas, who had an apartment upstairs above brother Nick’s tavern. Jack would sometimes stay there if he’d had too much to drink. The next year, Kerouac moved to St. Petersburg. “Tony got a phone call from Jack the night before he died,” Sampas says ruefully. “He was drunk, as usual, and wanted to talk. Tony was in bed with his girlfriend and had to cut the call short.” I remind Sampas of something John Clellon Holmes said in one of the Kerouac documentaries: that even when drunk, Jack’s talk was always brilliant, but that he had become a monologist, no longer interested in conversation.

The “formal” part of our interview has given way to relaxed conversation. Sampas recounts a story of how one of Kerouac’s notebooks ended up in the University of Texas collection. “I knew from Jack’s own journals that it was one that had been stolen. He complained that his friends were taking his stuff. I traced it and found that the dealer who sold it to Texas had purchased it from Gregory Corso.” We share a laugh: bad boy Gregory.

Outside the snow is continuing to pile up. I put on my coat and say goodbye. Sampas wishes me careful driving. Henry, who has been lying quietly on the floor the whole time, perks up for a head rub.

“One of the things I didn’t mention,” Sampas says as if it has waited ‘til now to occur to him, “is looking after Jack’s grave. You’ve been out to see it?”

“Many times,” I assure him.

Later that year, the estate oversaw a new headstone at Edson Cemetery.

John Sampas died in 2017; he was 84.

Note:: Check out Night of 100 Kerouac Poems: Blues & Haikus Marathon Reading. On the eve of Jack Kerouac’s 100th birthday 100 of his musical blues choruses and American haiku poems will be read aloud. Light refreshments and music from multi-instrumentalist Ken Field. On March 11, 6 to 8 p.m, 401 Merrimack Street, Lowell, MA.

David Daniel is author of many books, including White Rabbit, a novel of the Sixties and Inflections & Innuendos, a collection of flash fiction. He teaches part-time at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell and blogs regularly at richardhowe.com.

A very nice glimpse of a person and material that most people know nothing about. It made me appreciate the Herculean task that Sampas was given.

Intriguing.

I am reminded of how many writers are forgotten over time who have made, influenced art as it now is. How much richer our writing and reading would be if we just went a little further back in history. How much different our lives would be.

Thanks.

He made history. He contributed more than an armed revolution to change our lives for the better bringing us out of stereotypes, and he brought the sight of beauty and the example of the kind courage to live. We must honor and thank him as well as those who work to keep his word and life as luve. Thank you.

Without wonderfully dedicated people like John Sampas we wouldn’t have all these unpublished treasures that take us even further on the great journey of Jack’s sacred path to end of the land sadness, end of the land gladness.

Dave, you did a great job in here of presenting Mr. Sampas–I believe you introduced me to him back when you did the reading in Lowell that a bunch of Tamarackers attended. I remember him as being exactly as you have presented him–quiet and serious and I would think difficult to write about, but you did a great job of capturing him. And you both did a good job of giving us a glimpse of what the job of literary executor entails–it’s not one I would want, and no wise writer would choose me to fill that role.