Visual Arts Review: Friction Among Minimalists

By Eva Rosenfeld

Seeing Eleanor Antin’s 100 Boots all in one place is exciting — this work of “postal art” is still explosive. Fred Sandback’s minimalist pieces offer a quiet contrast.

Parts and Time and Axis — Twelve Points, Six Axes, No. 2 at Krakow Witkin Gallery, Newbury Street, Boston, through February 24.

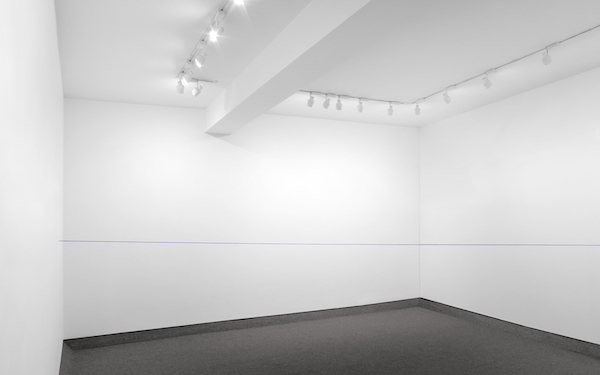

Fred Sandback, Untitled (Sculptural Study, Axis – Twelve Points, Six Axes, no. 2) c. 1974/2022 Blue acrylic yarn. Exhibition view. Photo: Krakow Witkin Gallery

Artist Fred Sandback first envisioned Axis–Twelve Points, Six Axes, no. 2 in 1974. The work is a piece of blue yarn suspended 44 inches above the ground, to be repeatedly installed along six rotating axes. It is being installed and photographed for the first time at the Krakow Witkin Gallery. Documenting the creation of Axis was the catalyst for Parts and Time, a companion show that features four works, including Eleanor Antin’s 100 Boots, that play off Axis’s fundamental themes of time, space, and serialization.

Sandback was born in Bronxville, NY, in 1943 and died by suicide in 2003. For those who appreciate his severely minimalist vision, his barely there works — which often made use of yarn — generate immense and mysterious transformations in their surroundings. For artist Andrea Fraser, what’s most emotionally striking about his Sandback’s perspective was its embrace of the quiet: “Not that he did so much with so little, but that he did so little.”

Sandback relinquished authority over the significance of his lines of yarn, hedging when asked in what ways he thought they functioned in carving up space. He would only say that they were intuitions. He was more assertive about what his works were not — not illusionistic, not environmental, not blueprints. He used cheap yarn because it held taut and was convenient: he could carry all the materials he needed for exhibitions in a bag.

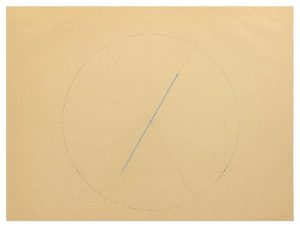

Fred Sandback, Untitled, 1974. Pastel, pen, and pencil on paper. Photo: Krakow Witkin Gallery

From 1981 to 1996, the DIA Art Foundation operated the Fred Sandback Museum in Winchendon, MA. After years of making works so spare they could be lost in a pocket, the prospect of physical space initially pleased Sandback — it gave him a sense of permanence. But once he designed the space and it become a reality, he became creatively restless. He was left yearning for disassembly. “Perhaps indeed,” he once wrote, “I have nomadicized my existence.” Sandback’s Untitled is also on display, though it is not officially on the roster for Parts and Time. It sits, like a mysterious cipher, at the edge of the gallery’s slightly aslant architecture.

Visitors would be mistaken if they think there is something to decode. “The actuality is the idea,” wrote Sandback, and his work and the pieces in Parts and Time do not pose problems, just experiences. They have no fixed meaning beyond themselves.

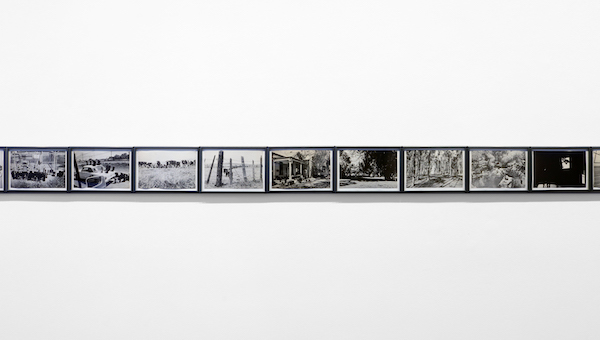

Still, despite reflecting an agreement on concept, the show presents a profound clash of personalities. Its gravitational center is 1972’s 100 Boots, a series of 51 photographic postcards that Eleanor Antin mailed out between 1971 and 1973. The photos follow 50 pairs of rubber US military surplus boots as they roam Southern California. At the end of their journey, they travel cross-country, explore New York, and retire to the MoMA.

Antin was born in 1935 to a helter-skelter family of Polish, Jewish, and Russian immigrants in the Bronx. In her art she examines the idea that she possesses a unified female self. Her conviction is that the “usual aids to self-definition — sex, age, talent, time and space” are “tyrannical limitations upon my freedom of choice.” One of her counters to custom is Selves — a work made up of prolonged multimedia explorations of other possible versions of herself. Nearly 20 years before critic Judith Butler articulated the concept of gender performativity, Antin dramatized the notion that gender is not something we have, but something we do. Her best-known contribution to feminist arts is Carving: A Traditional Sculpture, in which she “carved” away at herself drawing on instructions from a fad diet sourced from a women’s magazine. Over a period of 36 days she documented her nude body through a series of clinical photographs. Her intent was to satirically jab at the patriarchal images promoted by classical art, commercial media, and the bare, masculine-friendly look of so many conceptual artists.

100 Boots invited the participation of others. Fluxus artists were already doing “postal art,” but Antin introduced a new subjectivity and sociability, inspired by the serial narrative form. She listed 1,000 friends and artists and mailed the first cards out to them without any explanation. Some felt harassed; others cheered on the adventures of the boots. People read about the project in local papers and requested to be added to the list. Antin added them. She lacked technical photography skills, so she recruited Phillip Steinmetz to help execute the photos. The pair dragged the boots around California, continually scouting new locations.

Eleanor Antin’s 100 Boots. Exhibition view. Photo: Krakow Witkin Gallery

At the time of mailing, the boots told an archetypal tale — Antin called it a picaresque — that reflected an ongoing trauma in America’s political and cultural life. In May 1971, after weeks of protesting the Vietnam War, the boots broke free of restrictions and trespassed a chain link fence. They hung around in nature, found a job, got sacked, visited a cemetery, and went out drinking. They joined the army. In this somewhat comic scenario, the boots journeyed through the middle of a wartime society: Antin used tiny visual cues to give the boots “personality.” The photos are not intended to make concrete political statements or offer new ways of seeing the war. They represent a highly subjective and expansive way of interpreting the historical present, guided by Antin’s skepticism of fixed meaning.

Because of the nature of their distribution, the cards are not available on the art market but were part of the ephemera market, floating around in used book stores. MOMA has a full set, but otherwise 100 Boots has rarely been completely assembled. An industrious fan could theoretically gather them.

The juxtaposition of Antin and Sandback’s works produces surprising emotional friction. Seeing 100 Boots all in one place is exciting — they still seem explosive. Sandback’s pieces feel less involving. He likened his sculptural designs to musical scores. When asked about how future curators might approach them, he responded cooly, “Inevitably, after a certain point, it can’t be my problem and that’s fine.” More helpfully, he wrote at one time that his art is “about making a little place — just for yourself, or to share with someone.” Sandback’s solution to loneliness was to carve out a private space that others could join at will. In contrast, Antin instructed in a letter to students at the Feminist Art Program in 1974 that “art is the most communal activity in the world.” The irony is that, for her, fighting for a place in the art world was an assertive but lonely quest.

Eva Rosenfeld is a writer and artist from Michigan based in Cambridge, MA.

Thank you so much for taking the time to write about our exhibition and we are so sorry for our delay to write to you to thank you! We appreciate your support and look forward to having you come again !