Film Review: “2nd Chance” – A Memorable American Con Artist

By David D’Arcy

With Richard Davis, director Ramin Bahrani found an old-fashioned fraud, a paunchy American grifter worthy of a story by Mark Twain.

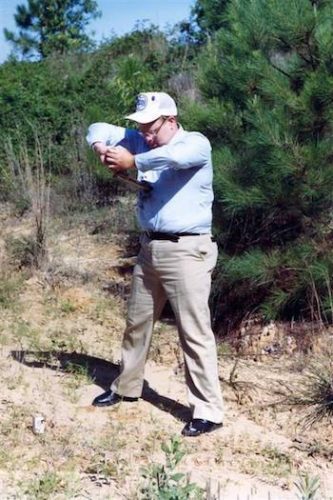

A scene from 2nd Chance. Photo: Sundance Institute

2nd Chance, one of my favorite films at Sundance this year, is Ramin Bahrani’s documentary about a wisecracking entrepreneur from the American heartland who rebounds from financial collapse by coming up with a product — a bullet-proof vest — that saves lives. Until it sinks him.

Richard Davis is a gifted salesman who was also an unrelenting liar, a conman who put the lives of those who trusted him at risk, not to mention the lives of his customers. Risk is a serious understatement when the product being sold to police is a faulty bullet-proof vest.

[Or an airplane. At this year’s Sundance, Rory Kennedy’s documentary Downfall: The Case Against Boeing explored the deceit behind a deadly tragedy. Corporate executives were found by investigators to have concealed crucial operating details about its aggressively highly marketed Boeing 737 Max from the pilots flying it. Two of those planes crashed, killing everyone aboard. The Boeing executives who tried to explain that maneuver lacked Davis’s charm.]

With Davis, director Ramin Bahrani found an old-fashioned fraud, a paunchy American grifter worthy of a story by Mark Twain. In a festival painfully short on comedy, 2nd Chance helped fill the gap.

Davis was a businessman in Detroit who owned two pizza restaurants that burned down in 1975, a time when a lot of that city was burning down. Broke, and without insurance (he said), Davis turned to his other vocation, inventing. Davis saw how crime was ravaging Detroit, with gun violence increasing every day. His solution was a bullet-proof vest, which he made out of synthetic fabric in his basement. Developing the product meant that he had to shoot himself wearing the vest in order to test it. He did that 192 times, by his own reckoning. If you don’t believe in your own product, he seemed to be saying, who else will?

Yes, you can see this testing on the screen. Davis loved filming himself.

A crucial event reinforced Davis’s commitment to producing a vest that would protect potential gunshot victims. Deputy Aaron Westrick was wearing the vest when he was chasing a suspect in Detroit — the cop escaped death when the suspect shot him. Westrick would defend Davis, and work for him, until too much truth about his boss surfaced.

With a wisecrack for every occasion, Davis could, as they say, make friends and influence people. And this heartland Falstaff was also making money on his product. He built a factory to manufacture Second Chance Armor Inc. vests in sleepy Central Lake in northern Michigan. He became the major employer, essentially owning the town.

Eventually Davis’s self-control frayed. He left his first wife. He targeted people who opposed him. His vests were shown to have flaws. One policeman died while wearing the vest and others were injured, while the money kept rolling in.

Even his story about the pizza fires proved to have some serious holes.

Yet the jokes kept coming, although Davis’s world collapsed.

Bahrani discretely lets the self-made and self-destructive American eccentric talk. Davis’s weird stories sound like they might have been told by the odd characters in the films of Errol Morris — Fred A. Leuchter, the designer of electric chairs (and denier of the Holocaust), or the self-promoting fabulist Joyce McKinney in Tabloid (2010), or Donald Rumsfeld, another Morris doc subject who told his own share of tall tales. We’re still living with the consequences of some of those.

America’s near-infinite array of odd characters is familiar territory for Bahrani. Before writing and directing his screen adaptation of the wild and sprawling Indian novel The White Tiger, Bahrani made small, closely observed documentaries that were built on improbable or overwhelming real life situations — a struggling food vendor on Wall Street in Man Push Cart (2005), two boys on the unpaved anarchic streets of the Willets Point neighborhood of Queens (now gone) in Chop Shop (2007), and a Senegalese immigrant driving a cab in Winston-Salem, NC, in Goodbye Solo (2008). He was as ready as any filmmaker for Richard Davis’s self-mythologizing.

Richard Davis — shooting himself to sell his bullet-proof vest.

As soon as we meet Davis, we see — what else? — footage of him shooting himself to test prototypes of his vest. These filmed performances, of Davis turning a gun on himself and surviving, are an old twist on the frontier magic shows where a performer would saw an assistant (usually a woman) in half. Davis understood that performance boosted sales; he filmed his own movies to sell the vests. One of those efforts was eight hours long. But let’s not forget that the bullets were real. And you can just hear somebody ask, “If a guy is willing to shoot himself that many times, how could he be lying?”

The Second Chance vest was, understandably, a huge media story: the creation of any successful product that saves lives would be. The downfall of a local hero also rallied the media. Still, Davis’s homespun charisma was just as huge an invitation for coverage. People whom he betrayed, and who turned on him (Westrick worked with law enforcement and wore a wire to record him), still speak fondly of the man. I’ll admit that, without loving or admiring Davis, I’m eager to watch 2nd Chance again and see him charm whoever would listen.

The American landscape is full of local rogues who strike it rich and attract fans. It helped that Davis, as both chronicler and subject, was an improviser who invented himself as he went along.

The stories within that story are hard to resist — a fraudulent “life-saving” product that didn’t work at key moments, a dead vest-wearing cop and his tearful young widow, the religious conversion of the man who went to prison for shooting Aaron Westrick (and, as Westrick did, earned a PhD.), Davis’s ex-wives talking up a storm, money from buyers of the vests all over the world, and forgiveness — yes, forgiveness in Central Lake, a quiet place, except for Davis’s gunshots. Move over, Garrison Keillor.

Forgiveness is the surprisingly encouraging final note to a film about a man willing (if not hellbent) to sell faulty bulletproof vests to policemen, and ready to abandon a town where he was effectively the sole source of income.

Davis’s downfall comes with the collapse of the Second Chance vest, its downfall the triumph of facts and evidence over sales pitch. The factory where the vests were made closed in 2009. Never admitting guilt, in 2018 Davis forfeited his assets and settled a government lawsuit that alleged that he made “false claims.”

Yet for those still drawn to Davis, the truth wasn’t enough to dim his star power. When love competes with mere facts, there is pressure, as Bahrani notes (quoting from John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance), to print the legend.

Fighting American fraud and corruption is one thing. Fighting national credulity, as we’ve seen with Davis and other charlatans, is a bigger problem.

2nd Chance somehow got scant media coverage at Sundance, although it’s now been acquired by Netflix, where you can already see Bahrani’s ambitious White Tiger.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.