February Short Fuses – Materia Critica

Television

Netflix’s Murderville proves to be an effective mix of mirth and mayhem.

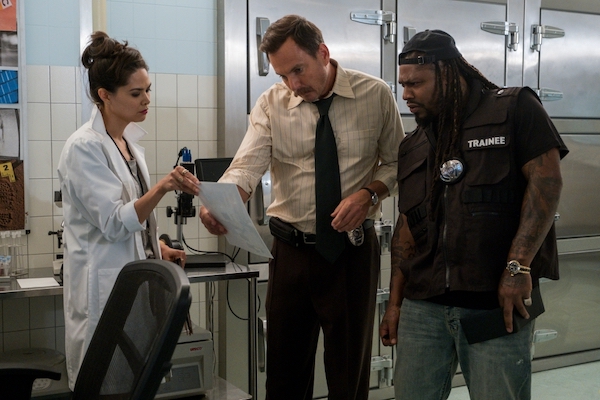

Marshawn Lynch in Murderville. Photo: Darren Michaels/Netflix.

Netflix’s latest series, Murderville, takes the traditional CSI procedural and gives it a unique twist: in every episode, Detective Terry Seattle (Will Arnett) has to solve a new murder with the help of a new celebrity partner, who doesn’t been given the episode’s script. While the rest of the cast knows who the murderer is, the celebrity partner is clueless and hs to improvise their way through the episode and then determine who dun it. Based on the BBC Three series, Murder in Successville, Murderville turns out to a perfectly silly antidote to bland cop procedurals.

Surprisingly, the best celebrity guest star turns out be be one who hasn’t been trained in improv — professional football running back Marshawn Lynch. While guest stars Conan O’Brien and Annie Murphy play their characters as straight as possible, Lynch leans into the utter absurdity of the series. He openly admits he has never had an urge to be a homicide detective; he asks if he can formally change his name to Detective Bagabitch. Lynch has great fun with the contrived set-up and his lack of acting experience turns out to be a huge benefit. Frankly, a series in which Lynch and Arnett alone have to solve murders together would be a welcome spinoff.

While Lynch is the most entertaining of the celebrity guests, the others hold their own against Arnett. O’Brien manages to keep a straight face as he tries to interview a possible murder suspect who is also a magician. He has to contend with Arnett reacting with growing enthusiasm to every magic reveal. Kumail Nanjiani can barely contain his giggles as Arnett tries to teach him how to do a cool walk. The result: Nanjiani ends up strolling along like a wounded monkey. Murphy somehow doesn’t crack when she goes undercover as a breakfast mobster who specializes in Connecticut pancakes.

Arnett and his boss/ex-wife (Haneefah Wood) nimbly support the star sherlocks. The episodes generally follow the same structure, but enough oddball details are tossed in to keep the celebrity guests on their toes and viewers from figuring out the murderer too soon. Murderville proves to be an effective mix of mirth and mayhem.

— Sarah Osman

Classical Music

It’s an agreeable performance, perhaps Daniel Barenboim’s most naturally felt traversal of the Strauss-era canon to date.

It’s sometimes an open question just what, musically, a conductor brings to the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra’s annual New Year’s Concert. The orchestra’s got this music so much in its collective bloodstream that, should he (and only men have conducted the event thus far) get too involved in the process, the risk of interference seems much greater than the promise of elevation.

It’s sometimes an open question just what, musically, a conductor brings to the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra’s annual New Year’s Concert. The orchestra’s got this music so much in its collective bloodstream that, should he (and only men have conducted the event thus far) get too involved in the process, the risk of interference seems much greater than the promise of elevation.

Granted, a small number of conductors have managed the latter, most notably Herbert von Karajan in 1987 and Carlos Kleiber in 1989. This year’s concert (Sony Classical) led, for the third time by Daniel Barenboim, isn’t quite to that level (the K’s both drew a higher degree of polish from the Overture to Die Fledermaus, for one). But it’s an agreeable performance, all the same, perhaps Barenboim’s most naturally felt traversal of the Strauss-era canon to date.

Part of this, no doubt, owes to the fact that, for the first time in two years, the concert was played to a live audience, and the Philharmonic sounds clearly enthused. Accordingly, there’s a good bit of swagger to the opening Phönix-Marsch and all of the up-tempo music is plenty nimble. At the same time, Barenboim and Co. tease out the peculiar melancholy of the repertoire when they can (like in the touching introduction to Johann Strauss Jr.’s Tausend und eine Nacht).

The most intriguing offerings are, as usual, the New Year’s Concert premieres. This year there were six of them, fully a third of the program. None break particularly new ground, though Carl Michael Ziehrer’s Nachtschwärmer waltzes showcase the VPO as a surprisingly sonorous choir. Still, the context they provide for the old favorites — be that Josef Strauss’s Sphärenklänge or Johann Jr.’s Morgenblätter — is more than welcome.

This recording from the Novus String Quartet is a reminder that Dmitri Shostakovich wrote a number of impressive quartets.

Given its prominence in his discography, one could be forgiven for thinking that the only quartet by Dmitri Shostakovich worth hearing is the Eighth. But the other 14 quartets aren’t necessarily pushovers, as a new Aparté recording from the Novus String Quartet that pairs the 1946 String Quartet no. 3 with the seminal 1960 score reminds.

Given its prominence in his discography, one could be forgiven for thinking that the only quartet by Dmitri Shostakovich worth hearing is the Eighth. But the other 14 quartets aren’t necessarily pushovers, as a new Aparté recording from the Novus String Quartet that pairs the 1946 String Quartet no. 3 with the seminal 1960 score reminds.

The Third Quartet occupies less fraught emotional terrain than the Eighth. Its five movements, though they offer some harrowing turns, also channel folk-like naiveté and operatic drama.

This performance draws out the score’s complexities. The first movement, generally warm and rounded rather than raw, offers a certain elegance. But it storms mightily, too. In the second, the ensemble shapes the music’s exchange of surging phrases and staccato refrains grippingly.

They bring rhythmic tautness to the central Allegro non troppo, while the Adagio’s alternations of fervent calls and spare responses come off impressively. So, too, the violin-cello dialogues in the finale: in this performance they’re imbued with a particular brilliance of character.

Coming after this, the Eighth is a bit of a letdown.

Not that it’s badly played. Much of the reading is clean textured and well directed. The ensemble’s tonal blend is miraculous, their dovetailing of its contrapuntal lines flawless. Best is the stormy second movement, with its tightly coiled, punching interjections and big dynamic range.

In the last three, though, the Novus’s tendency toward beauty of tone and smoothness of line undercuts the music’s intensity.

The Allegretto, though it moves nicely, is too graceful, especially at the beginning. Likewise, the fourth isn’t as massive or ferocious as it needs to be. Nor is the transition between the radiant, exposed cello melody and the knocking motive anywhere near as shattering as the moment demands.

Regardless, Aparté’s recorded sound is excellent.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Film

Sundown is a mostly absorbing arthouse thriller set high and low in Acapulco, Mexico.

Tim Roth taking in some sun in Sundown.

I am a great fan of movies, usually European and/or arthouse ones, in which you are told almost nothing about the characters. You don’t know their backstories or what supposedly motivates them, and there is little psychologizing. You learn about them mostly by observing them closely on screen. And so it is with Neil Bennett, a taciturn Tim Roth in Mexican director Michel Franco’s English-language film, Sundown (opening today at Cambridge’s Kendall Square Cinema and Brookline’s Coolidge Corner Theatre) He’s on vacation with his family, Alice Bennett (Charlotte Gainsbourg) and two teenagers, at an extremely high-end resort in Acapulco. Alice seems to run the show while Neil recedes into the background, taking private swims and barely speaking. It takes a long time to find out that the two Bennetts aren’t husband and wife but brother and sister, the two kids are hers, and that they are co-owners in England of a very lucrative meatpacking plant.

The fancy vacation is interrupted by news that their mother has died back in England. Alice cries, Neil is passive, though feigning concern. But when the family reaches the airport, returning to England to plan a funeral, Neil suddenly, impulsively acts. He claims to have forgotten his passport, saying he will join his family in several days. Not true. Instead, his existentialist self kicks in, as he becomes a changed person choosing an extraordinarily flipped-out life. He moves into a dowdy hotel in downtown Acapulco and hangs out at the locals’ crowded, polluted beach, spending his days on the sand drinking beers and passing time. Without really thinking much about it, he finds himself in a romance with a Mexican shop owner (Inzu Larios). Their sex is great, and she really appreciates him. They don’t have much conversation but they walk through town holding hands.

But a dangerous place, Acapulco. They are witness to a gang murder on the beach, and then something truly terrible occurs to a member of the Bennett family. Maybe too much plot suddenly drops into a movie in which things had been so pleasantly quiet: jail scenes, a fatal disease, a possible suicide. But Sundown is mostly a success with the always absorbing Tim Roth occupying the frame and with director Franco’s gala tour of all sides, high and low, of colorful, sometimes lethal Acapulco.

Breaking Bread is a mostly appealing documentary set in Israeli restaurant kitchens during an annual Arab food festival. It makes the obvious point that Arabs and Jews would get along infinitely better in Israel if they actually managed to know each other.

Lamb dumplings in Breaking Bread.

Anyone with any sense knows that Arabs and Jews, so similar, would get along infinitely better in Israel if they actually managed to know each other. Breaking Bread (begins screening in Boston on February 11), a mostly appealing documentary by an American filmmaker, Beth Elise Hawk, is one of a series of films over the years that have dramatized this point. In this case, we see Arab and Jewish chefs united in cooking for the three days in Haifa of an annual Arab food festival. 35 restaurants — all Jewish-owned? — dedicate their menus to very traditional Arabic dishes, the rarer and more ancient the better. For those days, a guest Arabic chef is brought into the kitchen to share cooking duties and to teach the Jewish chef how to make some esoteric, disappearing item from earlier times.

If you are food-crazy like I am, and also someone who cooks, you can’t help being entranced seeing so many fresh-ingredient ethnic dishes being prepared before your eyes. What is more beautiful than the sight of newly made Middle Eastern hummus with chickpeas and a golden drizzle of olive oil? And, yes, it’s moving to see the chefs with such different backgrounds uniting over their obsession with excellence in cuisine. Indeed, some new friendships are forged, but, curiously, there is none of the traditional “learning” of didactic films. The chefs we see are all eager to meet and work with their counterparts from a different ethnicity. Presumably, the chosen chefs volunteered to participate in the Arab food festival. It would have been interesting to interview a racist or two who would mix in the kitchen only over their dead bodies.

But Breaking Bread is not that kind of film, courting controversy. Every single character on camera echoes endlessly the same message: to hell with politicians (no names are mentioned), who are trying to divide us. We should just get along. The biggest cheerleader, and surely the filmmaker’s spokesperson, is Dr. Nof Atamner-Ismaeel, the Israeli Arab chef who started this project. She’s a great human being, an amazing optimist, but her view of Israel unfortunately does not jibe with the reality. Simply, it is not true that 90% of the people want to be friends with each other, and that 10% ruin it for everyone. Israel today — with its great food! — is a red state, as red as Alabama.

— Gerald Peary

Visual Art

I don’t want rain on any art lover’s parade, but Disneyfication is about technology in the service of profit.

The author sinks into Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience.

“If you build it, they will come.” That was my first thought after seeing Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience (installed at the Strand Theatre in Dorchester through February 20). And come they did, to 12 European and 13 US cities. In the exhibit’s review section, one Kenny P. declares: “I’ve been to a lot of showings of famous art in fabulous galleries but this was the most awe inspiring installation I have ever experienced.” Sold yet?

Even critics need to get out of the house. And so, following delays involving dates and a venue, we braved the cold and traffic, donned Covid masks, grabbed vaccination cards, and headed off to the Strand Theater. This was not the usual museum crowd, so the budget reproductions of the art in the lobby — accompanied by cards abut the artist’s life — were just there to warm you up. 3D installations offered photo ops. Then, we stood in line for the big event. The masked couple in front of us had driven up from Rhode Island.“We’re from one of the least vaccinated cities in the state” they confessed, as they dropped their masks to indulge in the wine bar.

Entering, we were lucky enough to grab two chairs and gaze up at 360 degrees of shifting images that floated, morphed, dripped, and flew across the 40-foot walls, the ceiling, and the floor. Occasionally, Google-search-level quotes about the blessings of art would pop up.

I don’t want rain on any art lover’s parade, but Disneyfication is about technology in the service of profit.

Next up? How about an “Andy Warhol Immersion” where you sit in a room and people look at each other for 8 hours? Or, better yet, the “Duchamp Experience” — bring your own toilet.

— Tim Jackson

Books

This book is a deeply felt tribute and a gift to all of us.

Rodrigo Garcia’s elegant slip of a book (the actual text is 110 pages) is a son’s meditation on the death of his father. The Nobel Prize–winning novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez died in 2014 at the age of 87. The film director and writer Rodrigo Garcia was born in 1959.

Rodrigo Garcia’s elegant slip of a book (the actual text is 110 pages) is a son’s meditation on the death of his father. The Nobel Prize–winning novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez died in 2014 at the age of 87. The film director and writer Rodrigo Garcia was born in 1959.

I was interested in reading A Farewell to Gabo and Mercedes: A Son’s Memoir of Gabriel García Márquez and Mercedes Barcha (Harpervia) not so much for insights into the world-famous father, but into his sweeping effect on his son. “Writing about the death of a loved one must be as old as writing itself, and yet the inclination to do it instantly ties me up in knots,” Rodrigo writes. “I am appalled that I am thinking about taking notes, ashamed as I take notes, disappointed in myself as I take notes.”

Although I’m not a fan of magical realism, I was a devotee of In Treatment, the HBO show that Rodrigo both wrote for and directed. I knew I would find his take on the writer and his death of interest, and it was. Though the parents Gabo and Mercedes live in Mexico City, Rodrigo and his family in L.A., and his brother Gonzalo and his family in Paris, they are close-knit, and this little book shows how they come together in the crisis occasioned by Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s dementia and then the months of his terminal illness at home.

Rodrigo is a compelling narrator. I was interested in everything he had to say, about himself, his upbringing, his parents’ relationship, his father’s trajectory from a small village in Colombia to Mexico City, where he died. The writer was aware of his memory deteriorating: “He would say, ‘I work with my memory. Memory is my tool and raw material. I cannot work without it. Help me.’ And then he would repeat it in one form or another multiple times an hour for half an afternoon. It was grueling.”

This little book is a memorial. It gives us mini-portraits of the four primary family members, glimpses of how they interact over a lifetime and during a prolonged medical crisis with their extended family, medical staff, the large group of friends and colleagues who want to say good-bye, with the press, with thousands of readers who gather in the street. It is a deeply felt tribute and a gift to all of us.

We need to hear more about Buster Keaton’s sublime art, particularly an updated appreciation of his clowning that will appeal to younger audiences who haven’t much (if any) sense of the physical comedy traditions Keaton tapped into.

There are already too many biographies of silent film genius Buster Keaton, but another one is coming later this month: James Curtis’s two-ton (832 pages) Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life. Is there any need for another go-through of the unfortunate pratfalls that the cinematic clown took in real life, aided by two unwise marriages and career-ending alcoholism? At the turn-of-the century Keaton was tossed about on stage by his father as part of a successful vaudeville act, made brilliant comedy shorts and features that dovetailed inventive laughs with risks to life and limb in the ’20s, and lost it all with the arrival of sound and subservience to a malign MGM studio system in the ’30s. Keaton made an admirable comeback on TV in the ’50s and ’60s, living long enough to bask in the critical and popular rediscovery of his masterpieces, which include Sherlock Jr. (1924), The General (1926), and Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928).

There are already too many biographies of silent film genius Buster Keaton, but another one is coming later this month: James Curtis’s two-ton (832 pages) Buster Keaton: A Filmmaker’s Life. Is there any need for another go-through of the unfortunate pratfalls that the cinematic clown took in real life, aided by two unwise marriages and career-ending alcoholism? At the turn-of-the century Keaton was tossed about on stage by his father as part of a successful vaudeville act, made brilliant comedy shorts and features that dovetailed inventive laughs with risks to life and limb in the ’20s, and lost it all with the arrival of sound and subservience to a malign MGM studio system in the ’30s. Keaton made an admirable comeback on TV in the ’50s and ’60s, living long enough to bask in the critical and popular rediscovery of his masterpieces, which include Sherlock Jr. (1924), The General (1926), and Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928).

We need to hear more about his sublime art, particularly an updated appreciation of his clowning that will appeal to younger audiences who haven’t much (if any) sense of the physical comedy traditions Keaton tapped into and — through inspired moviemaking — transcended. Critic James Agee undertook this duty when he helped to resurrect Keaton in his fine 1949 essay. What this silent film giant deserves now is the kind of in-depth analysis of his life, working methods, and wondrous artistry that Joseph McBride gives Ernst Lubitsch in his magisterial study How Did Lubitsch Do It? How did Keaton do it? — and why does that matter now?

In Camera Man: Buster Keaton, The Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the 20th Century (Atria), Slate film critic Dana Stevens heads in the opposite direction. For some reason, she is convinced that examining the ups and downs of Keaton’s career will help us understand the development of American modernity. Ironically, when she chooses to focus on the comic’s films, Stevens can be perceptive, particularly about the antic nihilistic short Cops (1922) and the satiric relationship of One Week (1920) to the creation and sales of prefabricated houses. And on occasion her wandering around the social/political margins pays dividends. She does an interesting job talking about how the Keaton family ran afoul of the Gerry Society, New York’s pioneering child protective agency, and Keaton’s use of blackface in one of his weaker films, College (1927), is suitably critiqued. But does Keaton’s life and art shed all that much light on the 20th century? Stevens does not make a compelling case. The truth is that, at times, she wanders afield because she is bored by the comedian. Despite all her proclamations of love, Stevens is content to turn Keaton into a cameo player, sort of like MGM. There’s a chapter dedicated to silent film comedian Mabel Normand, a potted history of Alcoholic Anonymous, a detailed homage to film critic and playwright Robert Sherwood (who worked on an unproduced script with Keaton), and a tired recycling of the plight of F. Scott Fitzgerald, another alcoholic mistreated by MGM, and the mystique of Irving Thalberg. And you learn more about the evolution of Childs Restaurants, one of the first national dining chains, than you ever cared to know.

Stevens and I both think that Steamboat Bill Jr. is the pinnacle of Keaton’s achievement, but she doesn’t examine that film in sufficient detail. She talks, often, about his most famous death-defying stunt — surviving a collapsing wall in a hurricane via a strategically placed window. But there is little about Keaton’s pantomime during his attempt to break his father out of jail, one of his greatest extended exercises in silent film mime. Some films are not mentioned at all — Go West (1925), for example. Others, such as Sherlock Jr. and The Navigator (1924), are said to be important but get short shrift. As for exploring Keaton’s connections with modernity, Stevens approaches making some provocative points, but pulls back. On the one hand, there is a darkness in Keaton’s work (missing in Charlie Chaplin) that reflects one strain of modernism. But, while the critic notes that the Harlem Renaissance offered a more optimistic version of modernism, she leaves it at that. It is worth taking a syncretic step forward: perhaps Keaton’s comic vision, with his drive to survive and succeed (or at least win the heroine), represents a fusion of both modernisms, a high-wire circus act in which the inventive overcoming of hostile obstacles takes place over an abyss.

Because it does not concentrate on Keaton’s art, Camera Man is irritatingly spotty. Intelligent insights alternate with filler, including the “questions that cannot be answered” wheeze: “As for movies … what would have happened if Keaton had been alive to witness the definitive demise of the studio system that had stifled his creative freedom in the 1920s? What might he have made of the industry-changing violence of Bonnie and Clyde, released just a year and a half after his death, or the art-house explosion of the mid to late 1960s: Bergman and Kubrick and Cassavetes?” Would Keaton have dismissed CGI? Who knows? Who cares?

Early in the book, Stevens claims that 1895, when Keaton was born (the same year as her grandfather), was a pivotal year. For me, a better candidate — when it comes to illuminating the 20th century — born that year was the celebrated “intellectual outlaw” Buckminister Fuller, architect, engineer, businessman, philosopher, and futurist. Twice expelled from Harvard University, Fuller overcame depression and penury to become an international figure, a practical and imaginative artist of ideas who argued, according to the New Yorker‘s Calvin Tomkins, that for “the first time in history man has the ability to play a conscious, active role in his own evolution, and therefore to make himself a complete success in his environment.” Fuller was coming up with the term “Spaceship Earth,” raising funds for pragmatic applications of his invention, the geodesic dome, inaugurating the World Design Science Decade, and working on his book Utopia or Oblivion while Keaton was filming Beach Blanket Bingo (1965).

— Bill Marx

Tagged: A Farewell to Gabo and Mercedes, Breaking Bread, Buster Keaton, Camera Man, Dana Stevens, Gerald Peary, Jonathan Blumhofer, Michel Franco, Murderville, Novus String Quartet, Rodrigo Garcia, Sarah Osman, Sony Classical, Sundown, Tim Jackson, Tim Roth

We all agree that Steamboat Bill, Jr. is Keaton’s very best. It’s also his warmest film. I haven’t read the book, but I can say that I would welcome reading some of Stevens’s off-subject chapters. I want to know about Mabel Normand and I’d be delighted to learn more about Robert Sherwood. Finally, that’s a pretty mean ending about Buster Keaton and Beach Blanket Bingo. Keaton had fallen completely out of favor in his later years, and he could only get the most minor roles. Only Samuel Beckett valued him enough to have him star in Beckett’s only cinema venture, Film. Oh by the way, I LIKE Beach Blanket Bingo. It’s the best of the beach films, with Harvey Lembeck’s hilarious parody of Brando in the Wild One, his character of Eric Von Zipper.

The chapters that depart from Keaton are informative, but they don’t say much about her protagonist — and the selections are based on Stevens’ whim. Why nothing on the making of Beach Blanket Bingo, for instance? I remember being amused by the film decades ago. One viewing was enough — there are so many better movies that I haven’t seen.

As for satirizing Brando in The Wild One, with all due respect for Harvey Lembeck, Brando does a better (and funnier) job of self-parody in some of his later films.

Ross Lipman’s NotFilm is a fine “kino-documentary” about the making of Film, a miserable experience for all concerned — Buster Keaton had no idea what it was about and Samuel Beckett put the kibosh any of Keaton’s attempts to add humor to what is a dry-as-ashes exercise in existential angst. It was theater director Alan Schneider’s first (and only?) film. He and Beckett initially approached Charlie Chaplin, Zero Mostel, and Jack MacGowran before settling on Keaton. It is not very good.

Stevens tells an amusing story about how Keaton made Beckett laugh on set. But she doesn’t make any claims for the aesthetic value of Film. The critic writes that Keaton’s last hurrah as an artist were his brilliant performances as part of Paris’s Medrano Circus during the late ’40s.

I didn’t intend to be mean-spirited at the end of the review. Stevens argues that Keaton was somehow part of the invention of the 20th century. But, as an artist, his greatness ended by the early ’30s. Buckminster Fuller’s career ranged longer and I would say, in its combination of pioneering science and aesthetics, reflected and shaped the century in more significant ways. Both were astonishing products of 1895.