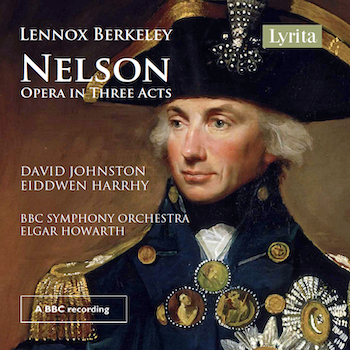

Opera Album Review: A Scandalous Liaison Makes a Wonderful Opera: Lennox Berkeley’s “Nelson”

By Ralph P. Locke

Berkeley’s Nelson reinforces my sense that many fine composers of the 20th century have largely slid off the map because they did not cater to the obsession of many critics and academics with “the New at all cost.”

Lennox Berkeley, Nelson

Eiddwen Harrhy (Emma Hamilton), Mary Thomas (Madame Serafin), Margaret Kingsley (Lady Nelson), Elizabeth Bainbridge (Mrs. Cadogan), David Johnston (Adm. Nelson), Brian Rayner Cook (William Hamilton), Richard Angas (Adm. Hardy), and others.

BBC Singers and Symphony/ Elgar Howarth.

Lyrita SRCD 2392 [2 CDs] 130 minutes.

Lennox Berkeley (1903-1989) is mainly known to American music lovers and record collectors for his instrumental works, which show the influence of France (not least his extensive study with Nadia Boulanger and his friendship with Ravel and Poulenc). The cumulative index to American Record Guide (but beginning only in 1987) shows a handful of vocal works as well: e.g., some songs, some sacred choral works, and two of his three one-act operas, A Dinner Engagement and Ruth. Berkeley was a friend and collaborator of Benjamin Britten. But, at any given point in their intertwined careers, Berkeley tended to be more traditional (conservative, choose your preferred word) in his musical language, though he did experiment with 12-tone writing in later years. His son Michael is a prominent British composer as well, much appreciated in North America and likewise extensively reviewed in newspapers and record magazines.

Lennox Berkeley (1903-1989) is mainly known to American music lovers and record collectors for his instrumental works, which show the influence of France (not least his extensive study with Nadia Boulanger and his friendship with Ravel and Poulenc). The cumulative index to American Record Guide (but beginning only in 1987) shows a handful of vocal works as well: e.g., some songs, some sacred choral works, and two of his three one-act operas, A Dinner Engagement and Ruth. Berkeley was a friend and collaborator of Benjamin Britten. But, at any given point in their intertwined careers, Berkeley tended to be more traditional (conservative, choose your preferred word) in his musical language, though he did experiment with 12-tone writing in later years. His son Michael is a prominent British composer as well, much appreciated in North America and likewise extensively reviewed in newspapers and record magazines.

Here, suddenly, is the belated first release of a 1983 BBC broadcast of Lennox Berkeley’s 1954 opera Nelson, a firmly tonal work dealing with the infamous (then and now) long-term affair between Admiral Horatio Nelson and Lady Emma Hamilton. Berkeley’s only full-length opera, Nelson was considered a relative disappointment at the time. But it has had its persistent admirers, a chorus that I now happily join. Berkeley thought at times of revising it but never did.

Nelson has occasionally been revived in concert, in part or whole, notably in a 1988 performance by the Chelsea Opera Group, with the 28-year-old Gerald Finley in the role of Emma’s husband William. Readers who wish to know more will greatly enjoy two books by composer-pianist-scholar Peter Dickinson: The Music of Lennox Berkeley and Lennox Berkeley and Friends (both Boydell Press).

The recording heard here was made in the BBC studios and was first broadcast in 1983. It is one of many broadcasts of often-unusual works that a devoted British radio listener, Richard Itter, recorded off the air — using excellent equipment — and that are now being released, with permission of the BBC and the musicians’ union.

The story of Nelson’s long infatuation with Emma Hamilton has been told repeatedly in history books, novels, and films, including, That Hamilton Woman, a 1941 film that starred Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier. For his operatic treatment of the couple’s story, Berkeley enlisted a prominent writer, Alan Pryce-Jones, to create the libretto. Pryce-Jones was editor of the Times Literary Supplement. His literary skill and historical knowledge are apparent throughout.

Act 1 shows us Admiral Nelson and Lady Hamilton meeting and falling in love in Naples, surrounded by their spouses and crowds of courtiers and onlookers. A fortune-teller predicts that Nelson will someday have to choose between love and duty.

Act 2 is, for me, the core of the work. Its first scene, 10 years later, includes a soliloquy for Lady Nelson that becomes a tense duet with Nelson (over his widely known relationship with Emma Hamilton), then a quartet involving the two married couples, and then a sextet (by adding in Mrs. Cadogan — who is Emma’s mother — and Admiral Hardy, whose function in the opera is to remind Nelson of his duty to the nation).

The second scene of Act 2 is equally well shaped. It takes place another five years later, a few weeks before the Battle of Trafalgar, and thus might more clearly have been called Act 3. It could still follow the preceding scene without an intermission; opera houses do this all the time nowadays with certain standard-repertory works, thus maintaining dramatic tension from one act to the next.

The scene includes a throbbingly vivid duet for Nelson and Emma, in which he (as predicted by the fortune-teller) must decide whether to risk his life leading the troops against the French and Spaniards or stay alive with the woman he loves. His soliloquy toward the end of the scene is gripping, thanks in part to surges — I’m tempted to say “waves” or “billows” — of commentary from the orchestra.

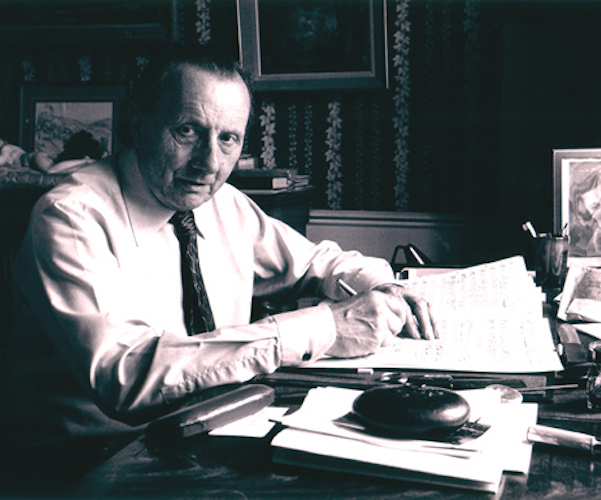

Composer Lennox Berkeley at his desk. Photo: lennoxberkeley.org.uk

Act 3 (though I’d call it Act 4) takes place during and after the famous battle off the coast of Spain. It includes a stirring patriotic chorus, an orchestral interlude portraying, with near-visual specificity, the Battle of Trafalgar and the gunfire that fells Nelson; a touching solo for the national hero as he expires from the wound; deeply moving responses to his death from the men around him (soloists and chorus) and from the orchestra alone in another marvelous interlude; and a powerful final solo for Emma: desolate but determined now to keep alive the renown of the man she loved. (As indeed the real Emma Hamilton tried valiantly, if also self-flatteringly, to do.)

As I have suggested, many scenes and moments in the work are intensely involving. We are dealing here with a most accomplished composer who knows how to draw us in with attractive melodic material, fresh-sounding harmonies, and an orchestral fabric full of arresting figurations, combinations, and contrasts (as well as contrasting melodic lines in vocal ensembles).

The music is tonal in a way that reminds me at times of Poulenc, the lyrical side of Prokofiev, or the more genial aspects of neoclassical Stravinsky. Occasional snatches of music evoke late-18th-century minuets and such, filtered at times through a sensibility akin to that of the Prokofiev “Classical” Symphony. The quartet and sextet, and several soliloquies and duets, could all make splendid material for “opera scenes” concerts at high-level conservatories and music schools. Either of the two scenes of Act 2 would work well as a shapely, self-contained mini-opera on a program of selected acts from forgotten operas.

I found myself getting impatient at times in Act 1. (Attempts have been made to tighten this act, which many have found problematic.) From then on, the work clicks into gear. The music for, and responding to, the fatally wounded Nelson (in the final act) is as stirring as anything I have heard in an unfamiliar work in a long while. The role of Nelson was taken by the great Peter Pears when the opera was given a preliminary performance with piano accompaniment.

Throughout, the singers and chorus are highly capable, and it helps greatly that they’re singing in their native language. The vocal qualities of the individual solo singers contrast with each other enough to help us know who is singing most of the time. But diction is sometimes mushy; I often had to glance at the printed libretto. Long-held notes sometimes waver a bit, but the intended pitch is always clear.

I particularly enjoyed Margaret Kingsley as Nelson’s outraged and emotionally abandoned wife (her tone firmer than that of some of the others) and Elizabeth Bainbridge as Emma’s mother. Kingsley was new to me, but Bainbridge is familiar to record collectors from, among other things, her splendid Sorceress on the Colin Davis/Josephine Veasey recording of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. The orchestra, as recorded, is a bit recessed, but comes to the fore in the instrumental interludes. Renowned conductor Elgar Howarth definitely has his finger on the work’s pulse.

Benjamin Britten (l) and Lennox Berkeley. Photo: lennoxberkeley.org.uk

All in all, Berkeley’s Nelson — which I had not even known existed until this recording came to my door — reinforces my sense that many fine composers of the 20th century have largely slid off the map because they did not cater to the obsession of many critics and academics with “the New at all cost.” If opera houses and philharmonic and recital halls won’t bring us the many beautifully crafted and moving works by such composers (six diverse cases: Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari, Jean Françaix, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, John Joubert, Gottfried von Einem, and Carlisle Floyd), then record companies have the field to themselves. Bravo to Lyrita for doing its part in bringing important works from the recent past to new generations of listeners! The recording is available at PrestoMusic and through Spotify and other streaming services.

One big annoyance, though: the track numbers are not stated in the synopsis or libretto, nor are there vertical lines showing passages that are sung simultaneously. The track-list mentions only the singer first heard in a track, plus her or his first words — no indication whether a given track is, say, a soliloquy or a sextet. As a result of all this, I had trouble locating again many passages that I wanted to rehear. The printed libretto omits, I believe, Mrs. Cadogan’s lines in the splendid sextet.

I see that Berkeley’s other three operas (all one-acters) are promised for release soon by Lyrita, boxed together. One of these is his best-known stage work, A Dinner Engagement, likewise from 1954. I hope that each of them has such a (basically) well-shaped libretto and such insightful music for it.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: BBC Singers and Symphony, Elgar Howarth., Lennox Berkeley, Lord Nelson