Film Feature: Making “Speer Goes to Hollywood”

By Thomas Doherty

Speer Goes to Hollywood, directed by Vanessa Lapa. Written by Lapa and Joëlle Alexis.

Albert Speer, Hitler’s pet architect and the vaunted “glamour boy of the Third Reich,” would have hated Vanessa Lapa’s unblinking and unforgiving documentary, which is the best recommendation I can give it.

In Luke Holland and Paul Yule’s Good Morning, Mr. Hitler (1993), a compilation of color home movies chronicling Hitler’s visit to Munich in the summer of 1939, Nazi propaganda minister Josef Goebbels — club-footed, 5 foot 5, rat-faced — can be seen glaring at Albert Speer, Hitler’s pet architect and the vaunted “glamour boy of the Third Reich.” Tall, handsome, and elegant, Speer positively glows in the warm sun of what the locals called “Hitler weather.” Goebbels’s gaze radiates envy and hate, mostly hate.

Israeli filmmaker Vanessa Lapa shares only the hate, though she too finds it hard to look away. In her mesmerizing documentary Speer Goes to Hollywood, Speer is on screen almost every second and when he is not being seen his words are being heard in voiceover recollection. Lapa culled material from over 47 visual and 9 audio sources to stitch together her portrait of the artist on the make, but not once is she enticed by the most urbane and charming of Hitler’s henchmen. She absolutely loathes “the liar and relentless manipulator” who diligently served Nazism as the sadistic “taskmaster of an army of slaves, 12 million weak, one-third of whom would die to feed his ambition.”

Lapa and co-writer Joëlle Alexis had plenty of forensic evidence to sift through. Speer’s Nazi prime and afterlife were exceptionally well-documented: private stashes of home movies, the newsreel record of the twelve-year Reich, the wall-to-wall motion picture coverage of the Nuremberg trials of 1945-1946, and the myriad television interviews conducted by Speer after his release from Spandau prison in 1966. Lapa’s tenacious archival digging is evident throughout the film, an international excavation project that dredged up heretofore unseen (to my eyes anyway) footage of Speer, whom even before donning a snazzy Nazi uniform was photogenic enough for newsreel cameramen to pick him out in a crowd. Yet the prize treasure from the media vault, the archival find that structures Lapa’s film, is audio not visual — forty hours of conversations between the then-novice screenwriter Andrew Birkin and Speer, recorded in 1971-72 at Speer’s home in Heidelberg, as the two workshopped a screenplay for a Great Nazi Biopic in development by British producers David Puttnam and Sandy Lieberson for Paramount Pictures.

The title is a misdirection. Unlike Hitler’s other pet artist, Leni Riefenstahl, who did indeed go to Hollywood to try to land a studio distribution deal for Olympia in 1938 (and who was roundly snubbed by the moguls), Speer never went to Hollywood to take a meeting and pitch his life story. Yet after the publication in 1969 of his best-selling memoir Inside the Third Reich, Hollywood was the logical end game. “The idea that my book should be filmed is a nightmare to me,” Speer wrote Birkin early on in the process, but clearly he’s living the dream. Speer’s only stipulation was that since “the book is of a certain quality, the film cannot be beneath that.”

The cassette tapes preserving the conversations rotate on a portable cassette player, often shown in close-up, a sonic source that will bring a pang of recognition to interviewers from an age before iPhones. As the two men speak and blue-pencil the script, scene by scene, they are voiced by off-screen actors (Anno Köhler for Speer, Jeremy Portnoi for Birkin) in a manner so natural and convincing that, when the end credits roll, viewers may be startled to find that the originals were not actually speaking. It really does seem like you’re eavesdropping on a private work session. More about this later.

The outline of Speer’s own rise and fall is well known, but hearing him flesh out the details as the images unspool is spellbinding. In 1931, the aspiring young architect, a son of patrician privilege, heard Hitler speak and was hooked. “I think it was love at the first sight,” Speer almost sighs. He joined the Nazi party and remained under Hitler’s spell until the very end.

Nazism provided Speer with a massive outdoor canvas long before it gave him construction sites and city blocks. Perhaps only Goebbels and Riefenstahl played greater roles in forging the visual iconography of the Third Reich. Speer helped orchestrate the orgiastic rallies strewn with swastikas and lit by high-intensity Klieg lights. The operatic set design and lighting schemes are still very much in vogue in the Marvel Cinematic Universe and arena-sized rock and roll shows.

Channeling Hitler’s Aryan monumentalism and penchant for Valhalla kitsch, Speer drew up plans to reshape the landscape and skyline of Berlin. “You are fulfilling my dream,” Hitler tells him. Speer admits that for the chance to rebuild an entire city “I really would have sold my soul to Mephisto,” which cues up clips from F. W. Murnau’s Faust (1926) in case we miss the reference. Yet Speer did not have to be seduced by the devil: he leapt into bed. When World War II breaks out, he anticipates only a great adventure and relishes the lebensraum for his blueprints. “I shall be the architect of the new Napoleon!”

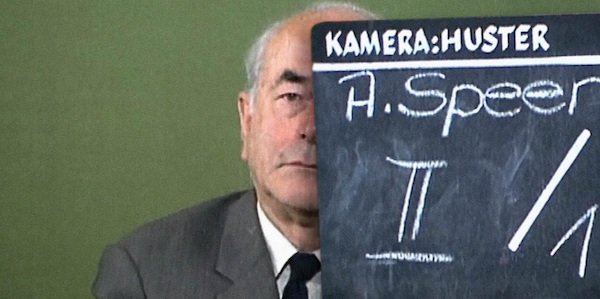

Albert Speer in a scene from Speer Goes to Hollywood,

But it was his role as a destroyer not a builder that put Speer in the dock at Nuremberg. In 1942, when Fritz Todt, Minister of Armaments and Munitions, was killed in a plane crash, Hitler appointed Speer as replacement. The counterintuitive selection was a stroke of genius. As Hitler knew from Speer’s exquisite on-time restoration of the Reich Chancellery, the architect was a brilliant organizer and hands-on administrator. Despite saturation Allied bombing, he kept the Nazi war machine roaring long after the rest of the engines had sputtered and died. At one point, he had 12 million workers under his jackboot, slave laborers, many worked to death, in service to the arms of Krupp and the missiles of von Braun. Nazi newsreels show a smiling Speer on the test sites, atop the tanks, happy to get out of the office to have what he remembers as “good fun.” The war, Speer knew, was lost at Stalingrad, but he never slacked off.

In the very last days of the Third Reich, Speer risked his life to bid farewell to Hitler in his bunker. When Birkin refers to the unfolding Gotterdammerung as “the eleventh hour,” Speer responds laconically, “It was the twelfth hour past already.” Speer famously claimed to have contemplated assassinating Hitler by releasing poison gas into a ventilation shaft in the bunker, but in his memoir he admitted that he could never really have gone through with what Birkin calls his “James Bond bit.”

Speer is actually surprised and hurt that Hitler showed no concern for him, his family, or anyone else. “Not one word of pitying me or the fate of the German people or anything like that,” recalls Speer. “Nothing. Just for himself.”

Captured by the Allies and put on trial at Nuremberg for crimes against humanity (“Justice catches up with the monsters of fascism!” bellows a voice from an American newsreel), Speer played his cards perfectly. In the first newsreel pictures of a line-up of defeated Nazis, he cleverly wears a suit not a uniform. “I am not a fool,” he says, something we know by this time, and which the trial proceedings will confirm.

Lapa makes especially effective use of the Nuremberg trial footage, shot in crisp 35mm, by four sets of cameras in booths at each of the four corners of the courtroom. The courtroom footage is supplemented by film from the liberation of the concentration camps, shot by Allied cameramen, and later screened as Exhibit A by the prosecution. Some of the most incriminating reels were shot by the Nazis themselves. “It was like Dillinger having a camera crew following him,” an incredulous War Department official told Variety.

Speer’s life is on the line for the “extermination through work” of his slave laborers. Rather than murder Russian POWs and Jews outright, he wanted the raw material put to efficient use. “Well, it’s a waste of labor to us,” he says of his pragmatic approach. At Nuremberg, however, he blames the body count on Fritz Sauckel, head of labor deployment and Speer’s nominal subordinate. “I am not responsible for those things,” Speer insists. “It was him.”

During the trial, Speer slyly paid lip service to accepting responsibility (“Who else is to be held responsible for the course of events if not the closest associates around the Chief of State?”), but pled ignorance of the greatest crimes. “German executives were decent people who cared about their workers,” he testifies with a straight face. Lapa cross-cuts to a shot of a courtroom translator smiling grimly.

Whether sitting in the dock or on the witness stand, Speer looks like a professor, his first job, not a henchman, his second, which doubtless helped his case. As Sauckel testifies, a courtroom cameraman holds on a shot of Speer, who seems to look into the lens, not defiantly, but as if nothing here really concerns him. Yet Speer cannot escape a powerful j’accuse moment when a survivor stands up, stretches his arm out, and points at him as the visitor he saw at Gusen, a branch camp of the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria.

Whether sitting in the dock or on the witness stand, Speer looks like a professor, his first job, not a henchman, his second, which doubtless helped his case. As Sauckel testifies, a courtroom cameraman holds on a shot of Speer, who seems to look into the lens, not defiantly, but as if nothing here really concerns him. Yet Speer cannot escape a powerful j’accuse moment when a survivor stands up, stretches his arm out, and points at him as the visitor he saw at Gusen, a branch camp of the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria.

In 1971, taking up the prosecution’s case, Birkin tries to probe deeper. Was Speer at the infamous Final Solution speech to the S.S. given by Heinrich Himmler on October 6, 1943 at Poznan? “I can’t tell,” answers Speer, the detail man, his mind suddenly blank. “It must have been completely washed out of my memory. The whole thing.”

Later, Speer is more forthcoming. “Ja, of course. Indirectly I knew from Hitler he was planning to annihilate the Jewish people.” Yet he continues to maintain that he had “no direct knowledge until ’44” when a friend warns him to “never go to a camp in Upper Silesia because terrible things are happening there.” The camp “must have been Auschwitz.” Speer shrugs. “Small things” — the Holocaust — “are now seen as the center of a thing.”

As Birkin and Speer discuss the small things — and footage shows the emaciated bodies of the walking dead laborers in Speer’s workplaces — Speer suggests a break for lunch. Perhaps at a pleasant wine restaurant? It is almost too perfect.

Speer was lucky to get off with his life. When the verdict was pronounced, Herman Goering, who would cheat the hangman’s noose with a cyanide capsule, said that Speer, not Sauckel, should have gotten the death penalty. He had a point.

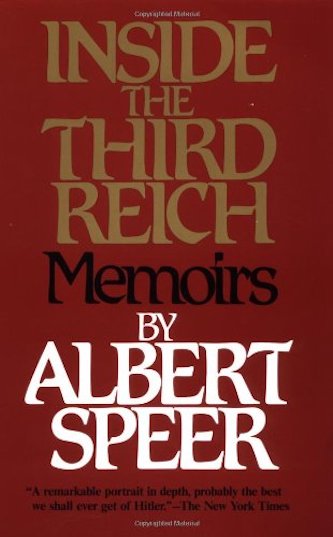

Upon his release from Spandau in 1966 after serving his full twenty-year sentence (the Soviets saw no reason to let him out for good behavior), Speer bathed in the celebrity of his third act. He took control of his story with his there-at-the-creation-and-destruction memoir, Inside the Third Reich, which lived up to its title. Among the voluminous entries in the card catalogue of Nazi scholarship, Speer’s account is on anyone’s short list of required reading: no one else had the proximity to power, the memory, and the intelligence. In 1970, reviewing the book for the New York Times, the historian John Toland called it “not only the most significant personal German account to come out of the war but the most revealing document on the Hitler phenomenon yet written.” The book was also praised for its narrative thrust and pithy character sketches. (“You can always count on a murderer for a fancy prose style,” Humbert Humbert reminds us.)

Inside the Third Reich turned Speer into a coveted get for journalists everywhere: a genuine high-level Nazi at the Führer’s right hand, ready to share anecdotes and spill the inside dope. Big name television journalists such as Charles Collingwood, David Frost, and Patrick Watson made the pilgrimage to Heidelberg for respectful one-on-one interviews. “The Last Nazi is now available in your market!” trumpeted trade ads for the Watson show.

Yet despite the success of the televised book tour and the seeming box office appeal of a pre-sold property, the motion picture adaptation is in trouble — and Birkin seems troubled, and not from being in development hell. For guidance, he speaks by telephone to the great director Carol Reed (voiced by Roger Ringross), who also happens to be his cousin and mentor. Reed tells the younger man, not unkindly, that Speer is playing him for a sucker. “You can’t build crematoriums like that without him knowing,” Reed insists. “He knew that they were being exterminated.” Reed says Speer’s culpability isn’t coming through in the script. “I’m just saying, Andrew, that I think Speer is whitewashed, you know?”

Birkin takes it all in, but he seems to have fallen hard for his subject and collaborator. The man is so genial and such a solicitous host. Are you hungry? Would you like a sherry? And smart. In the course of his conversation, Speer makes fluent references to Goethe, Sophocles, Voltaire, and Malraux — it’s not pretentious name-checking, but the natural erudition of an educated and cultured man. “I’m delighted that you weren’t [executed] or we wouldn’t have a film,” Birkin tells Speer, but the bond seems to go deeper than self-interest.

In retrospect, it is hard to tell if Speer and Birkin ever really did have a film. The project got far enough along to film a color screen test with Donald Pleasence as Hitler, (another archival gem, which Lapa unearthed at the British Film Institute). At one point, in wishful thinking mode, the pair speculates about whom to cast in the starring role. Looking at a photograph of a dashing Speer in Nazi uniform, Birkin suggests a young Marlon Brando type for the part — British actor Mark Burns? “Not bad at all,” allows Speer. (If you’re like me, you won’t resist the urge to play along and cast a period-appropriate actor to play Speer in 1971 — Christopher Plummer? Maximilian Schell?)

Rutger Hauer as Albert Speer and Blythe Danner as Speer’s wife Marguerite in a promo still from ABC’s 1982’s telecast Inside the Third Reich.

But the project is doomed and Birkin must break the bad news. There are “terrible problems” in Los Angeles. The executives at Paramount “read our script and felt it was a complete whitewash.” That word again. Out of a screenplay of 210 pages, only one or two pages addressed what was really going on inside the Third Reich, Paramount’s readers point out. Speer is impervious. “I think it’s really a masterpiece.”

In the end, Paramount passed. An epilogue sequence shows the media scrum after Speer’s release from Spandau. He enjoyed the spotlight until 1981, when he died in London of a cerebral hemorrhage, as he was preparing for a television interview.

Then, the startling end credit which reveals that the voices of “Speer” and “Birkin” have, all along, belonged to actors not the real speakers.

Andrew Birkin, who unlike Speer is very much alive, did not have to wait until the end credits rolled to know something was out of sync. In February 2020, after the film premiered at the Berlinale Film Festival, he posted a corrective on the Internet Movie Database. Not only did he not recognize his voice but he didn’t recognize the portrait of himself as a gullible stooge duped by the Nazi charmer. Lapa, he charged, “had imported quotes from Speer that he apparently said elsewhere, but not to me, and has therefore had to invent questions and responses from me that I naturally did not make. Many of these quotes do not matter to me, but when Speer is heard to spout antisemitic remarks, it reflects badly on me that I don’t take him to task.” Birkin also maintains that the reason the film went unproduced was not because Paramount got cold feet but because Costa-Gavras, originally slated to direct, backed out. The “Andrew Birkin” co-starring with Speer in Lapa’s film was a “cinematically constructed” character.

Film critic Glenn Kenny, who felt bushwhacked by the end-credit revelation, decided to dig deeper after Birkin contacted him with his objections. In an exemplary piece of journalistic legwork, he cross-checked accounts by Lapa, Birkin, and documentarian Errol Morris, who was initially involved with the project. Lapa insisted that, despite her use of vocal actors, “Nothing is re-created. Everything from the tapes is” — and here she emphasized the word — “re-recorded.” The quality of the 50-year-old analog cassette tapes was unsuitable for use on the digital soundtrack on the documentary, so the conversations were duplicated, she said, beat for beat, “every breath, every laugh, ever pause, every intonation.”

Birkin responded that Lapa’s claim of perfect fidelity to the original recordings was a “blatant lie.” Kenny, who was given access to the original tapes by Birkin, backs Birkin on both the audio quality of the originals and — crucially — on Lapa’s tweaking of the conversations.

Director Vanessa Lapa. Photo: YouTube.

In a recent conversation on Zoom, Lapa told me that she stood behind her decisions, that the soundtrack transcriptions were taken verbatim from the tapes, and that the film never pretended to draw solely on Birkin’s recordings. She estimated 76% of the talk came from the Birkin tapes, 24% from other audio sources. She noted too that, when the film opens, Speer is heard repeatedly talking in his own voice as he gives interviews after his release from Spandau. (Indeed, he is slyly introduced as a kindly old man who politely answers all his mail from readers of Inside the Third Reich.). So, argued Lapa, if the listener didn’t detect the subsequent reenactment, it is a “huge compliment” to the skill of the performers. “I didn’t have any intention to hide anything from the viewer,” Lapa insisted. “Editing is editing,” and the techniques employed in Speer Goes to Hollywood have been common in plenty of other documentary films. “We didn’t use anything that doesn’t exist.”

Still, why not simply put your cards on the table, I asked — open the film with a pre-credit crawl, not in tiny type at the end, acknowledging the performative nature of the off-screen voices and use printed supers to indicate the places where Birkin was not actually in conversation with Speer? Lapa remained adamant. “I stand behind the choice. For the cinematic experience, I would have made the same decision today. There was no reason to put [the vocal credits] at the beginning.”

(For myself, for what it is worth, I am not sure whether the paragraphs above should have a “spoiler alert” red flag. I felt surprised, though not suckered and resentful, upon learning of the vocal performers at the end of the film. Actually, I was grateful for the reminder to always watch a documentary with skeptical wariness.)

Though the Speer-Birkin screenplay was filed away, a year after Speer’s death in 1981, a docu-dramatic version of Inside the Third Reich finally reached the screen. Over two nights, on May 9-10, 1982, ABC telecast Inside the Third Reich, a five-hour mini-series based on Speer’s memoir, directed by Marvin J. Chomsky (Holocaust [1978]) and produced and written by E. Jack Neuman — who himself taped over 50 hours of conversations with Speer. Shot on location in and around Munich, the prestige production featured an all-star cast — Rutger Hauer (Speer), Blythe Danner (wife Marguerite), and Derek Jacobi (Hitler). The reviews were excellent. “Riveting television, truly a major event that helps further illuminate these monstrous events of the past,” wrote Ron Miller of the Knight-Ridder News Service.

The telefilm portrays a complicated man — flawed and complicit, to be sure, but not without courage, especially at the end when he refuses to execute Hitler’s orders for a “scorched earth” policy. Yet it is by no means a whitewash. Exposed as an amoral careerist, Speer is seen witnessing the beatings of Jews in the streets, visiting a forced labor camp under his supervision, and learning about (and sloughing off) news of Auschwitz. “I considered Speer — and still do — the ultimate dangerous Nazi,” said screenwriter Neuman at the time. “He knew better, and still he was a Nazi.” On the whole, however, I think Speer would not have been displeased with the portrait presented on television — and he would have loved the flattering casting.

Speer would have hated Lapa’s unblinking and unforgiving Speer Goes to Hollywood, though, which is the best recommendation I can give it.

Thomas Doherty is a professor of American studies at Brandeis University.

Tagged: Albert Speer, Andrew Birkin, Joëlle Alexis, Speer Goes to Hollywood, Thomas Doherty

A great piece! Nuanced, sensitive, and multifaceted. Thanks for this.

Thanks, Tom, for, as always being a great writer and an exemplary film historian.

Thoroughly great review Professor Doherty: both damning of the Nazi machine and Speer as a facilitator of the Reich’s atrocities while also laying out what makes him an interesting documentary subject. Clearly I learned from the best back at Brandeis. Hope you’re doing well!