November Short Fuses – Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Concert

After backing up Luther Vandross, Tina Turner, Chris Botti, Sting, the Rolling Stones, and the Nine Inch Nails, Lisa Fischer was given the opportunity to step into the spotlight — and she has found her own comfort zone.

Lisa Fischer at Rockport’s Shalin Liu Performance Center. Photo: Glenn Rifkin

It’s safe to say that Lisa Fischer has navigated her 20 feet into the spotlight brilliantly. If November 5th’s performance at Rockport Music’s magnificent Shalin Liu Performance Center, before a sold-out, masked-up audience of worshipers, was any indication, Fischer is most definitely a star in her own right. Among the featured backup singers in the 2013 Academy Award–winning documentary Twenty Feet from Stardom, Fischer has spent the last eight years wowing audiences all over the world since that film outed her prodigious talents.

At the Shalin Liu, an intimate 300-seat venue with remarkable acoustics and the ambiance of a supper club, Fischer demonstrated her vocal versatility with a mix of blues, rock, jazz, soul, and whimsy. Accompanied by stellar jazz pianist Taylor Eigsti, Fischer belted and crooned and seduced her way through such numbers as “Fever,” “Imagine,” “Blues in the Night,” “Ain’t No Sunshine,” and “Killing Me Softly.” She spoke of her mother’s love of Roberta Flack and how that love of music filled her childhood, setting her on an unalterable career path.

Her soaring, sensuous vocalizations, which swirl from deep bass to untethered octaves high in the clouds, are transfixing. When Sting called her a “powerhouse” in the documentary, he wasn’t exaggerating. At 62, after more than four decades as a vocalist, Fischer’s voice remains a powerful virtuoso instrument that she commands with practiced ease.

Beyond that stunning voice, Fischer’s enchanting stage presence bespeaks the person who long ago became deeply comfortable in her own skin. She embraces her audiences with a love and gratitude for a career shift that was unforeseen but most welcome. In return, she has already built a following of passionate fans who pack her shows knowing she won’t disappoint.

For someone who danced with Mick Jagger on Stones tours for more than a quarter century, Fischer knows how to sashay, more quietly but no less effectively, in smaller venues like the Shalin Liu. After backing up the likes of Luther Vandross, Tina Turner, Chris Botti, Sting, and the Nine Inch Nails, Fischer was given the opportunity to step into the spotlight — and she has found her own comfort zone. For her encore, she knocked out a spine-chilling rendition of “Gimme Shelter,” the signature Stones tune that featured her stunning backup vocals and showcased a star turn waiting to happen.

For tour dates: https://lisafischermusic.com/

— Glenn Rifkin

Classical Music

Pianist Stewart Goodyear scores with a mix of keyboard warhorses with some fresh contemporary works.

Pianist Stewart Goodyear’s latest disc, Phoenix, frames a series of favorite keyboard pieces by Claude Debussy and Modest Mussorgsky with a set of contemporary works that are just as bracing and characterful.

Pianist Stewart Goodyear’s latest disc, Phoenix, frames a series of favorite keyboard pieces by Claude Debussy and Modest Mussorgsky with a set of contemporary works that are just as bracing and characterful.

Two of them are by Goodyear himself: Congatay and Panorama. Both are extroverted and vigorous. The former’s insistent, motoric figures belie a cheerful, good-natured character, while the latter’s exuberance makes for a rousing closer.

They stand in stark contrast to Anthony Davis’s Middle Passage, a 10-minute-long meditation on Robert Hayden’s eponymous poem about the transit of slave ships to the Americas. Fittingly, the piece is filled with brisk, vaguely threatening keyboard lines that are often dense, rhythmically and texturally. They lead in unpredictable directions, interspersed by moments of relaxation and reflection that never seem to last long.

Balancing out the Goodyear and Davis contributions on this Bright Shiny Things release is Jennifer Higdon’s Secret and Glass Gardens, a virtuosic essay written for the 2000 Van Cliburn Competition whose many energetic flourishes unwind in a serene coda.

Heard in this context, Debussy’s Sunken Cathedral and L’isle joyeuse as well as Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition sound bracingly fresh.

True, Goodyear’s account of Sunken Cathedral, while warm, clean, and well-voiced, is a hair too fast to capture the music’s mystery and grandeur. But L’isle is bright and playful, evincing an impressively snappy, martial character over its central part.

Mussorgsky’s great Pictures is, in Goodyear’s hands, likewise characterful: full of bold contrasts (in “The Gnome”), soulful melodic lines (“Il Vecchio Castillo”), insouciant swagger (“The Market”), and slashing vigor (“Baba Yaga”). Throughout, there’s a terrific sense of direction to Goodyear’s reading as well as seamless exchanges of materials between the hands.

To be sure, the keyboard version of Pictures is a showpiece; here, it comes across as a particularly grand and majestic one.

The sheer wattage of Riccardo Muti’s soloists — Jessye Norman, Agnes Baltsa, José Carreras, and Yevgeny Nestrenko — is extraordinary

Few conductors of the last 50 years have wrung the Verdi Requiem for all it’s worth like Riccardo Muti. His three earlier recordings are, if not equally successful, at least consistently intense. So, too, in this newly released live account (BR Klassik) from 1981 with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (BRSO) and Chorus.

Few conductors of the last 50 years have wrung the Verdi Requiem for all it’s worth like Riccardo Muti. His three earlier recordings are, if not equally successful, at least consistently intense. So, too, in this newly released live account (BR Klassik) from 1981 with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (BRSO) and Chorus.

Here, again, Muti’s Verdi is blazingly directed and, often enough, electrifying. Throughout this performance, he implicitly trusts the music, pushing spots (like the opening of the “Dies irae”) while holding others back. But the results never feel mannered or indulgent.

On the contrary, this must have been an invigorating event, even if some of its climaxes come out shrilly on disc.

The sheer wattage of Muti’s soloists — Jessye Norman, Agnes Baltsa, José Carreras, and Yevgeny Nestrenko — is extraordinary. All were in their prime in 1981, and it tells. Norman’s high-tessitura singing is immaculate, Carreras’s tone resplendent. Together, the foursome sings with a potent mix of fervency and clarity.

The BRSO Chorus acquits itself admirably, projecting with power and subtlety (the blend between unison choir and orchestra at the beginning of the “Agnus Dei,” for instance, is perfectly calibrated). And the orchestra plays mightily, in moments explosive and quiet; the string tremolos at the start of the “Lux aeterna” shimmer with otherworldly energy.

So, how does this Requiem compare to Muti’s previous ones from, respectively, La Scala, the Philharmonia, and the Chicago Symphony? The La Scala performance offers a slightly starrier roster of soloists (Studer, Zajick, Pavarotti, and Ramey). The Philharmonia account boasts two of this disc’s headliners (Baltsa and Nestrenko) and some robust choral contributions, while the Chicago Symphony disc is a more technically satisfying recording.

But none of them have Norman singing the “Libera me” — and that must put this one at or near the top.

Everything hangs together thanks to cellist Hannah Collins’s remarkable virtuosity and musicianship.

Cellist Hannah Collins’s Resonance Lines is one of the year’s fascinating solo releases. Its program draws, primarily, on the last half-century, from Benjamin Britten’s Cello Suite no. 1 to Thomas Kotcheff’s Cadenza (with or without Haydn).

Cellist Hannah Collins’s Resonance Lines is one of the year’s fascinating solo releases. Its program draws, primarily, on the last half-century, from Benjamin Britten’s Cello Suite no. 1 to Thomas Kotcheff’s Cadenza (with or without Haydn).

The earliest selection, though, comes courtesy of the Baroque master Giuseppe Colombi, whose songful, majestic Chiacona sets the disc’s pace.

After that are Kaija Saariaho’s shimmering Dreaming Chaconne (from 2010) and Caroline Shaw’s in manus tuas, a 2009 homage to a Thomas Tallis motet.

Saariaho’s Sept Papillons, essentially a study in short gestural and sonic figures, serves as an introduction to Britten’s 1964 Suite, which, itself, sets up Kotcheff’s wild, wacky mash-up of all the music on this album — plus nods to Haydn’s C-major Cello Concerto.

Everything hangs together thanks to Collins’s remarkable virtuosity and musicianship.

There’s nothing easy about either of the Saariaho works, though thanks to Collins’s supremely confident and colorful playing, they come off as appealingly as one might hope.

Shaw’s in manus tuas shares some extended gestures with Dreaming Chaconne but ends up going in very different directions. Collins’s performances of both are richly colored and resonant, drawing out a huge range of colors from their pages.

She does the same in Britten’s great Suite which, in her hands, is well shaped and highly flexible. There’s a strong sense of style, character, and articulation in each movement, though the spotless intonation in the “Fuga” and tonal continuity of the “Bordone’s” drone deserve singling out.

Kotcheff’s inventive Cadenza is a dazzling showpiece. How the writing holds these disparate style and musical languages together is something that must be heard to be believed but — trust me — it manages. Collins isn’t once thrown by its demands; on the contrary: she owns them.

All in all, then, a brilliantly played and strongly recorded release on Sono Luminus.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

I loved each of pianist Angela Hewitt selections, as well as the way she plays each and every song.

I’ve only heard Angela Hewitt in person once, 10 years ago in a Celebrity Series of Boston presentation (review in the Arts Fuse). But I checked out her performances streamed during lockdown: she made several impressive broadcasts from London’s Wigmore Hall. Her Granados and Scarlatti were terrific. The pianist has a huge following, and rightly so. For years, she was known mostly for her Bach, but she is superb in pretty much whatever she plays.

I’ve only heard Angela Hewitt in person once, 10 years ago in a Celebrity Series of Boston presentation (review in the Arts Fuse). But I checked out her performances streamed during lockdown: she made several impressive broadcasts from London’s Wigmore Hall. Her Granados and Scarlatti were terrific. The pianist has a huge following, and rightly so. For years, she was known mostly for her Bach, but she is superb in pretty much whatever she plays.

I have listened to her newest release, Love songs (Hyperion), half a dozen times, and grow more impressed after each hearing. (You could say it was love at first listen.) Twenty years ago Hewitt had begun to muse about putting together a recording like this; COVID and the subsequent canceling of all of her concerts gave her the opportunity to bring this inspired project to fruition.

The first-rate repertoire here includes several familiar pieces, transcribed for piano solo by some great pianists — Franz Liszt, Walter Gieseking, the renowned accompanist Gerald Moore, and composer Max Reger (four Strauss songs). I had never heard — or imagined the possibility — of Hewitt’s piano solo arrangement of the spellbinding Adagietto from Gustav Mahler’s Symphony #5. This track alone makes the CD a must-have. Three beautiful renditions of songs by Robert Schumann open the recording, among them Schumann’s “Widmung” (“Dedication”), a perennial encore for many pianists. Two songs of Schubert and five of Richard Strauss follow, including Strauss’s “Morgen!,” which has become beloved via its customary orchestral version, which boasts huge parts for harp and violin. Fauré’s well-known song “Nell” is just lovely in its arrangement by Percy Grainger. And Gluck’s “Orpheus’s Lament and Dance of the Blessed Spirits” are sublime; the lament is another popular encore piece.

A big surprise to this listener was Manuel de Falla’s song cycle “Siete canciones populares españolas,” which I’d heard, and adored, countless times as performed on countless instruments. Hewitt chose five of these tunes, and they are spellbinding. Drawing on authentic folk songs from different regions of Spain, these songs — in arrangements by Ernesto Halffter, a student of de Falla — are wonderfully played. I will quote from my 2011 review: “Ms. Hewitt’s playing was hypnotically lovely. She has a beautiful touch, as piano teachers like to say, and her playing was colorful and always elegant … with exquisite attention to color, dynamics, and quicksilver mood changes.”

So, how do you follow a dazzling de Falla? Uncannily enough, with two Percy Grainger arrangements, Gershwin’s dreamy “Love Walked In” and a much-adored number originally called “Irish Tune from County Derry,” better known as “Danny Boy.” I now know what to get for my friends for the holidays.

— Susan Miron

Jazz

Lady Millea has a pleasant enough breathy voice, and she mostly stays in tune, but she’s in no way ready for the big time.

I dutifully listened to Lady Millea’s CD I Don’t Mind Missing You (Reconcile Records) when I received a copy, and I wasn’t planning to do so ever again. Then a few weeks later I got the promotional material: “We’re confident her heart-melting voice combining poignant purity with a sultry sophistication something akin to ‘Sarah Vaughan meets Karen Carpenter’ will redefine the current musical standard for unassuming elegance. Sprinkle it all with the mystique of a gracious, almost other-worldly ‘angel on assignment’ and you have a sonic masterpiece fit to entertain and enthrall, as well as elevate, enrich and enlighten everyone from plain folks to the most discriminating connoisseurs.”

I dutifully listened to Lady Millea’s CD I Don’t Mind Missing You (Reconcile Records) when I received a copy, and I wasn’t planning to do so ever again. Then a few weeks later I got the promotional material: “We’re confident her heart-melting voice combining poignant purity with a sultry sophistication something akin to ‘Sarah Vaughan meets Karen Carpenter’ will redefine the current musical standard for unassuming elegance. Sprinkle it all with the mystique of a gracious, almost other-worldly ‘angel on assignment’ and you have a sonic masterpiece fit to entertain and enthrall, as well as elevate, enrich and enlighten everyone from plain folks to the most discriminating connoisseurs.”

Um, did someone slip the new Veronica Swift album into this writer’s CD jacket? I wasn’t going to give this below-average album a review, but hype like this cannot be allowed to stand unchallenged. Millea has a pleasant enough breathy voice, and she mostly stays in tune, but she’s in no way ready for the big time. There’s nothing distinctive or memorable about her straightforward phrasing or approach. The nine songs on this debut album were written, arranged, and produced by her father, J. Frederick Millea (a.k.a. L.A. Cowboy, also releasing a new and better album at the same time). The songs are sometimes clever, but generally they’re standard-issue love songs that don’t fully commit to either jazz or folksy pop.

Millea is effusive with her praise of the competent band in the liner notes. “It was amazing to watch the rhythm section play together through each song one time while essentially improvising the organic sound.” Well, that’s what jazz musicians do. Even more embarrassing is her unsexy burlesque on “Hold Me,” complete with calling her keyboardist “boy,” oblivious to the meaning of that in jazz history.

One final snark: if the cover represents a new fashion trend, Heaven help us.

— Allen Michie

Books

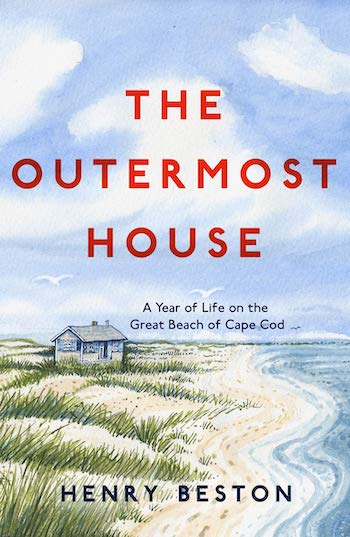

It may seem odd to review a nearly century-old book, but sometimes the past tosses up hidden gems that can’t be ignored. There’s a decent chance you haven’t read The Outermost House: A Year of Life on the Great Beach of Cape Cod by Henry Beston, published in 1928 and relegated in recent decades to the obscurity bin. My friend Peter who recommended it to me insisted it is considered a classic of nature writing, but I had not heard of it and neither has anyone I’ve told about it since I finished reading it.

It may seem odd to review a nearly century-old book, but sometimes the past tosses up hidden gems that can’t be ignored. There’s a decent chance you haven’t read The Outermost House: A Year of Life on the Great Beach of Cape Cod by Henry Beston, published in 1928 and relegated in recent decades to the obscurity bin. My friend Peter who recommended it to me insisted it is considered a classic of nature writing, but I had not heard of it and neither has anyone I’ve told about it since I finished reading it.

My sample size is not insignificant because I’ve been enthusiastically talking up this remarkable book, making clear that this beautiful memoir set in the mid-’20s on the outer Cape is as impressive as Thoreau’s Walden, upon which it was modeled.

Beston, a writer-naturalist, born in 1888 in Quincy, was in his mid-30s when he purchased 50 acres of land on the barrier beach in Eastham, just beyond the elbow of the Cape. He designed a two-room cottage on the dunes above Coast Guard Beach, then called Eastham Beach, with the intention of using it as a summer vacation spot. The outer Cape in the 1920s was an undeveloped place of unspoiled beauty, with its wide white sand beach stretching from Eastham to Provincetown. The local roadway out to Provincetown was designated Route 6 in 1926 but bore no resemblance to the Mid-Cape Highway it would become in the 1950s. The isolation and beauty was deeply alluring to Beston, and in 1926, after a two-week visit to the cottage, which he called The Fo’Castle, he decided to stay for a year.

‘The fortnight ending, I lingered on, and as the year lengthened into autumn, the beauty and mystery of this earth and outer sea so possessed and held me that I could not go,” he wrote.

He settled in alone and began keeping daily notes of his exploration of this miraculous land and seascape. He not only wrote about the dramatic shifts in the seasons, but focused his literary gifts on lyrical descriptions of the beach, the dunes, the birds, the sky and even the way the waves arrived on the shore. He told of a powerful February nor’easter that hit without the warnings we have today, pummeling his tiny home and churning up the sands and ocean into a terrifying maelstrom.

“I woke in the morning to the dry rattle of sleet on my eastern windows and the howling of wind. A northeaster laden with sleet was bearing down on the Cape from off a furious ocean, an ebbing sea fought with a gale blowing directly on the coast; the lonely desolation of the beach was a thousand times more desolate in that white storm pouring down from a dark sky.”

His sojourn was just a pile of notes until he returned from the Cape and his fiancée insisted that he turn it into a book. “No book, no wedding,” she declared. It was a fortuitous ultimatum because the resulting book is one of the finest examples of nature writing to emerge from these shores. It was published in 1928 to a tepid response, but over time its popularity grew and it achieved a kind of cult status. Rachel Carson claimed it was the only book that influenced her writing.

Beston’s concern for the planet and man’s nefarious touch that might lead to its ruination struck a chord, decades before climate change became an existential threat. In 1960, the book was cited as a motivating force for the creation of the Cape Cod National Seashore, and Massachusetts governor Endicott Peabody named the cottage a National Literary Landmark. It stood against the winds and forces of nature until 1978, when the Great Blizzard washed it out to sea.

Beston concluded his work with his elegant command: “Hold your hands out over the earth as over a flame. To all who love her, who open to her the doors of their veins, she gives of her strength, sustaining them with her own measureless tremor of life. Touch the earth, love the earth, honor the earth, her plains, her valleys, her hills, and her seas, rest your spirit in her solitary places. For the gifts of life are the earth’s and they are given to all, and they are the songs of birds at daybreak, Orion and the Bear, and dawn seen over ocean from the beach.”

— Glenn Rifkin

Rock

Tedeschi Trucks Band singer Alecia Chakour has released a new EP, lotusland.

Singer Alecia Chakour has long been an impressive supporting player, adding luster to performances by Lettuce, Warren Haynes, Eric Krasno, and the Tedeschi Trucks Band, in which she currently resides full time.

But with the EP lotusland, Chakour steps forward as commanding leader, offering up a satisfying blend of soul and R & B. The tracks have been run through a series of imaginative filters, in the process creating performances that are both haunting and rootsy.

Performing under the nom de plume Chakourah, the singer and arranger co-produced lotusland with her brother Alex Chakour, a sought-after multi-instrumentalist skilled at supporting great singers. He has worked extensively with both Charles Bradley and Sharon Jones and is currently in Brittany Howard’s band. The Chakour siblings also brought in a few collaborators, among them their father Mitch Chakour, who was for a time Joe Cocker’s bandleader.

The ambient lullaby “Undrowned” opens the EP, inviting the listener into Chakourah’s 20-minute dreamscape.

“West St.” gets things going in earnest, with layers of beats, keys, and vocal harmony ushering in Chakour’s gauzy lead vocal as she unspools a tale of love between a space traveler and earthling — Chakourah makes the tryst otherworldly in every way possible.

“Eagle Song #2” runs a country twang through the song’s soul foundation, atop which Chakour applies full, unvarnished vocals that hit crystalline highs and warm lows.

Chakour treks through some classic soul turf on “Wilson,” moving her vocal work with sprightly agility across rich sonic textures.

lotusland closes with the short organ interlude “Good Morning” that is an intro to “Red.” The finale is a slow burner that spotlights Chakour’s vocal acrobatics. She and her brother push the cinematic song to a lush conclusion before a bit of playful piano vamping arrives as audio credits roll.

The EP indicates that Chakour intends to keep exploring the intersection of traditional and modern styles via an enticingly organic approach.

— Scott McLennan

Theater

It is hard to figure what the playwright intends to have us think about this adaptation of a Jacobean “tragi-comedy.”

A scene from the Huntington Theatre Company production of Witch.

A Faustian bargain tempts at the Calderwood/BCA via the Huntington Theatre Company’s staging of Jen Silverman’s Witch, which is running through November 14. The drama might be: who will succumb and who will yield? And with what reasoning? This reimagining of a Jacobean “tragi-comedy” is less morally compromised — and more situation comedy — than the original. Four hundred years have passed since The Witch of Edmonton premiered, and this collaboration between Thomas Dekker, William Rowley, and John Ford is far harsher, darker, and messier than what Silverman has come up with. She keeps many of the same characters in Jacobean garb, but she has them speak a contemporary idiom while altering their fates and slimming down their complexities.

The original five-act drama features a talking dog, bigamy, a questionable pregnancy, dubious witchcraft, and a communal perspective. Here the stakes are lower, and so is the price to be paid to the assistant devil/Scratch (Michael Underhill). Elizabeth Sawyer (Lyndsay Allyn Cox) — the name of the actual woman on whom the play is based — does not die, as most eponymous characters in significant tragedies do. In fact, her story is almost obscured by the antics within two other plot lines that involve gentlepersons who dally in romance, inheritance, and sexuality. Despite one untimely death (male) and one condemned to domicile drudgery (female), what might be a meaningful high stakes conflict is dismissed with a shrug of no consequence. Save for one exhilarating moment — see below.

Did “the Devil make me do it,” as wry comedian Flip Wilson winked in his ’70s TV program? Or do we have freedom of choice? Does Silverman grapple with that question? Not really. In fact, it is hard to figure what the playwright intends to have us think about this adaptation. Feminism, at least understood as a rebellion against patriarchal power, is given limited traction in the arguments between Elizabeth and Scratch. She makes use of logic, but underlying their banter is her sly semi-seduction of the devil, which taints the trial. She claims that humans have free choice, which means Scratch does as well. The play’s devil responds that he is not human, but this excuse is belied by his delight in regaling how he loves choosing all the guises he takes in his wanderings about the world, which is frequently exploited as a punch line. Speaking of punch lines, Witch is played as farce most of the time, then it attempts to take a tragic turn. Its conclusion embraces quasi-philosophical deliberation, which is neither merited by the previous plots nor of much interest on its own.

Thanks to director Rebecca Bradshaw and the staging’s designers, the piece is visually sensible and sensitive. If you emerge from the theater humming the set, designed by Luciana Stecconi, the play has accomplished something. Cottage and castle merge and mutate, strong verticals and basic horizontals, high and low doors, consonant with social class, are convincingly lit by designer Mary Louise Geiger. The blend of would-be tragedy and comedy are represented in elegant proportions: props appear from above and below, primary colors versus earth tones, a mirror of social class. Only the preshow curtain, with its cartoon of a conventional witch, feels irrelevant, unnecessary, even purposely misleading.

Bradshaw does a more than admirable job in staging the scenes. She does not do so well, unfortunately, in shaping the performances. The stage pictures are often stark and clarifying, the tone amiss. Several of the cast push for humor, telegraphing laugh lines, announcing neither villainy nor virtue by alternating shouts or whispers.

With delight, I offer special kudos to fight director Ted Hewlett and to choreographer Misha Shield. In the dialogue-less fracas between Cuddy Banks (Nick Sulfaro) and Frank Thorney (Javier David Padilla) lies the true drama of this text. We witness the evolution and transition from touch to tantrum, arriving at the passionate (and frantic) agony of guilt as Shield transforms (or devolves) an existential wrestling match into a manic Morris Dance. If there is a reason to see Witch, this would be the scene.

— Joann Green Breuer

Tagged: Allen Michie, Angela-Hewitt, BR Klassik, Bright Shiny Things, Glenn, Glenn Rifkin, Hannah Collins, Hannah Kendall, Henry Beston, Huntington Theater Company, Hyperion, Joann Green Breuer, Jonathan Blumhofer, Lisa Fischer, Love songs, Phoenix, Resonance Line, Resonance Lines, Riccardo Muti, Shalin Liu Performance Center, Stewart Goodyear, Susan Miron, The Outermost House

What a pleasure to read Allen Miche’s witty slam of the hilariously over-hyped Lady Millea. When a father dutifully produces his daughter’s debut, watch out!