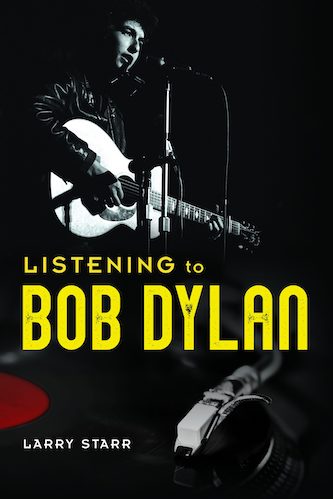

Book Review: To Compromise With the Mystery Tramp — A Vocal Dissection of Bob Dylan

By Daniel Gewertz

The book’s main contention is clearly correct: Dylan’s lyrics aren’t everything, and his vocal delivery is eminently important. But, according to Larry Starr, every period is a golden one, and the most minor effort deserves major respect.

Listening to Bob Dylan by Larry Starr. University of Illinois Press, 136 pages, $19.99.

There is no shelter from the storm of books written in recent years about Bob Dylan, but Larry Starr has managed to come up with a truly distinctive angle. The title is simple yet telling: Listening to Bob Dylan. An emeritus professor of music history at the University of Washington, Starr has written what amounts to an extended lecture analyzing the technical, musical facets of Dylan’s nearly 60 years of recorded music. He roundly ignores biography, storytelling, gossip, and even, to a large extent, literary analysis of Dylan’s lyrics. His slender, methodical book does not depend on interviews, anecdotes, firsthand accounts, or even his own experiences at Dylan concerts. (The chapter on live performances hinges on his listening to albums.) But concert attendance or no, make no mistake: Starr is a full-fledged Dylan fanatic.

There is no shelter from the storm of books written in recent years about Bob Dylan, but Larry Starr has managed to come up with a truly distinctive angle. The title is simple yet telling: Listening to Bob Dylan. An emeritus professor of music history at the University of Washington, Starr has written what amounts to an extended lecture analyzing the technical, musical facets of Dylan’s nearly 60 years of recorded music. He roundly ignores biography, storytelling, gossip, and even, to a large extent, literary analysis of Dylan’s lyrics. His slender, methodical book does not depend on interviews, anecdotes, firsthand accounts, or even his own experiences at Dylan concerts. (The chapter on live performances hinges on his listening to albums.) But concert attendance or no, make no mistake: Starr is a full-fledged Dylan fanatic.

The title Listening to Bob Dylan may also imply a reproach: Dylan’s biographical incidentals are not at the essence. Just listen to the goddamn songs! At first, the professor seems to have hit upon a canny idea: to dissect, elaborately, in music theory terms, what Dylan has been doing with his guitar, harmonica, band, and — most saliently — his vocal tones and inflections. It turns out that the very singer long thought of as a terrible vocalist by pop music illiterates is not only a “good” singer but — according to Starr — has long had a methodology to his seemingly instinctive style.

I can imagine Dylan fans buying the book as a curiosity and letting it sit on the shelf, but the truest audience for the book may be minuscule: a Dylan obsessive with a tolerance for academic writing who just happens to be a trained musician. Reading a few of Starr’s sharpest analyses will likely elicit smiles from any Dylan fan. Reading his best pages will convince them the book is touched by acuity. But reading the whole book? It may bore the bejesus out of them.

Starr’s most expansive chapter is his first, “Not By Words Alone.” It begins with one of the book’s few anecdotes: Dylan’s acceptance of the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature. Dylan stated in his Stockholm speech that “songs are unlike literature…. I hope some of you get the chance to listen to my lyrics the way they were intended to be heard: in concert or on record.” That is Starr’s credo here, but he focuses even further: listen to the sound itself.

Starr’s descriptions of Dylan’s shrewd vocal variations made me recall a prominent advertising slogan Columbia Records put out in 1965. The ad copy simply read, “Nobody Sings Dylan Like Dylan.” Back then, it was an almost shocking statement to the average pop music fan — the current wisdom was that Dylan was a genius songwriter who simply couldn’t sing! Hate is the word most often hurled at his vocals. So, when I read those words as a 15-year-old Dylan convert, I was elated. My belief was verified. I knew there was a powerful spirit emanating from Dylan’s voice, the sound of a dramatist, a comic, and a seer. In later years, with all sorts of unpretty voices on the Top 40, it became apparent to the masses that Dylan wasn’t quite the vocal anti-Christ.

Starr aptly describes Dylan’s vocal powers back then as far more powerful than those of the pleasant-voiced interpreters who spread his early songs. Take the simple phrase from the chorus of “Like a Rolling Stone”: “How does it feel?” That prosaic question by itself, Starr notes, is nothing a Nobel committee might consider high literature. But executed, it is one of the most primal lines in pop music history. Starr’s detailed technical analysis is spot-on. I especially love the way the author — by simple use of dashes, spaces, and capital letters — captures the singular Dylan delivery: the way the singer stretches some words like pizza dough and then mashes others together so they trip cunningly off the singer’s tongue and fall right into a song’s rhythmic pocket.

Many would agree with Starr that “Rolling Stone” is a historic rock single, a spree of scathing, vital wordplay and spell-like propulsion. Since sound is the essence of his book, the author doesn’t examine the meaning of the lyrics, or why a virtuoso put-down song bitterly aimed at a misguided young woman continues to thrill generations of fans. One might dismiss it as misogynist anger or laud it as a nonpolitical protest song. But the essential allure of this song goes beyond the specific lyrics. I myself had firsthand knowledge of this back in 1965, at age 15, when I saw Dylan’s controversial performance at Forest Hills Tennis Stadium in August, a month after its calamitous Newport debut. (That concert in Queens also presented the world premiere of “Desolation Row,” all 11-plus minutes of it!) To be honest, I had no clue why the fans sat in church-like silence during the acoustic half of the concert and reacted like incensed boo birds in the electric second act. “Like a Rolling Stone,” after all, was a Top 10 song at the time. I was just thrilled to be able to move on down to the expensive seats vacated by the folk purists. To me, “Rolling Stone,” much like Dylan’s other new songs — acoustic and electric — explored the singer’s alienation with a vituperative spirit that mirrored my own secluded anger. Though I was a lonely, bullied, privately angry teen, I identified with Dylan’s take on his very different world. And when I saw him booed and pelted with soda cans at Forest Hills, he became my victim/hero, a powerful combination.

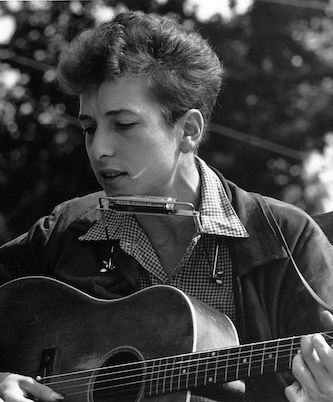

Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C.; close-up view of vocalist Bob Dylan, August 28, 1963. Photo: Wiki Common.

Though Starr’s book runs just 123 pages of text, it seems endless: a long-form music-theory college lecture: observant, ponderous, repetitive. A full chapter is devoted to Dylan’s harmonica work. The best way to read it may be a few pages at a time, followed by a long listen to the songs Starr has unpacked. The author states early on that he’s no music snob. “Underestimating — or even worse, condescending to — nonspecialists is a cultural offense that I have spent my entire career striving to avoid.” He then promises to avoid pretension and to explain basic terms as he goes along. Starr keeps generally true to his word, but there are exceptions. The professor regularly tosses in the phrase “strophic form” when delineating the structure of Dylan songs. You may pardon yourself if you’re not familiar with the phrase. Strophic, from the Greek, is a decidedly specialist term simply noting a piece of music with repeating sections, be they verse, chorus or refrain. In other words: practically every popular song ever written since at least the 19th century! Whatever his intentions, the overuse of the term becomes pure palaver.

Starr returns frequently to Dylan’s eponymous first album, recorded in November 1961 at age 20, and made up mostly of songs written by others. It is Starr’s contention that even in this early, Guthrie-idolizing stage, Dylan had many influences and had already set his sights upon a life of multiple vocal styles — the instinct that grew into persona “shape-shifting.” But Starr’s penchant is fawning praise, so he misses the arc and drama of Dylan’s career, the missteps and comebacks, the paths lost and found. Some utterly mediocre songs from more recent decades are honored with the same place at the artistic table as early gems. Take, for example, his comparison of Blonde on Blonde’s “Stuck Inside of Mobile With the Memphis Blues Again” (1966) with Under the Red Sky’s “Handy Dandy” (1990). What does a wit-laden moody classic have in common with a minor ditty deserving its obscurity? Just this — the word “time” appears in both, and both possess some typical Dylanesque vocal idiosyncrasies. But the darkly mordant humor and sophisticated nonsense of “Memphis” — sung in his most emotionally charged 1966 style, a peerless combination of foreboding and funny — has substantially zero in common with “Handy Dandy.” In ’66, Dylan knew exactly who he was and how to make a lyric as vocally indelible, in its own way, as a Hank Williams line. The lyric Starr quotes — “the people just get uglier and I have no sense of time” — echoes in my mind in much the same way a famous Beethoven figure might reverberate in the head of a classical music buff.

So. The book’s main contention is clearly correct — Dylan’s lyrics aren’t everything, and the vocal delivery is eminently important. Think of the wacky absurdist ditties from The Basement Tapes. There are many frisky little songs in his peak years that would’ve failed miserably if sung with the destroyed voice of this present decade. But according to Starr, every period is a golden one, and the most minor effort deserves major respect. When Starr zeros in on sturdy details such as Dylan’s gospel-inspired chordal piano playing on ominous or beseeching songs such as “Ballad of a Thin Man” and “Dear Landlord,” he strikes a genuinely perceptive note. Even his sub-chapter titles (“‘Visions of Johanna’: Lyrical Panorama, Musical Claustrophobia”) — display a sensitive grasp of Dylan’s best work. But when he gushes about Dylan’s supposedly brilliant 21st-century vocals, it makes one wonder what accolades the music professor might save for master stylists like Ray Charles, Stevie Wonder, or Judy Garland.

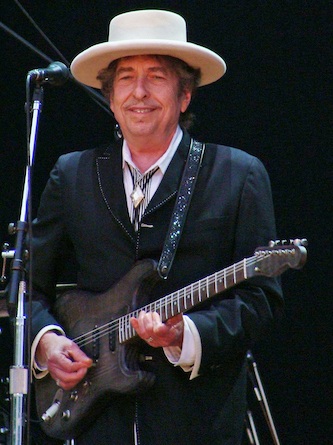

Bob Dylan in 2010 performing at the Azkena Rock Festival. Photo: Wiki Common

In the first of two chapters titled “Bob Dylan as Composer,” Starr assumes that Dylan is a melodic king among knaves: “If it’s a simple matter of fashioning a memorable tune, Dylan can deliver the goods when he wishes,” he writes. Writing a memorable melody a simple matter? It’s a surprising statement from the author of a book on George Gershwin. He then goes on to analyze “One More Night,” a song from Nashville Skyline. The hit from the album was “Lay Lady Lay,” and the one emotionally riveting jewel was “I Threw It All Away,” a song as deep in sorrowful feeling as it was well sung. But “One More Night”? A catchy, countrified little love song to be sure. It does stick in the mind. But according to Starr, the one segment where Dylan raises his voice an octave turns it into brilliant art. Why he makes such a big deal of this vocal move is baffling — especially since the octave lift, a common device, isn’t smoothly handled by Dylan. The aim here is a gleeful-sounding song of lonely sadness, like the merrier versions of “Sittin’ on Top of the World.” Starr claims that “Dylan’s tender rendering of these high notes exemplifies the synergy between composer and singer in his art and exemplifies also his technical skill as a singer.” It is these frequent raves for lesser work, and even weak renditions, that make a reader doubt his accolades for Dylan’s actual brilliance. And while Starr’s detailed analyses of song structures and musical strategies display academic knowledge, the author fails to convince that they are the reasons behind Dylan’s seer-like authority or career endurance.

Why has Dylan lasted as America’s deity of songwriting? How has he survived innumerable weak albums and an ever more ravaged voice to remain THE lauded one: the owner of a steady legion of zealous followers as well as the critical establishment? Starr details the many masks, poses, and voices Dylan has employed as a cultural “shape-shifter.” But there is no deeper scrutiny as to why the so-called shape-shifting has continued to fascinate.

Throughout the book, Starr the music prof essentially mixes it up with Starr the Dylan fanatic. In my estimation, the professor loses the match.

For 30 years, Daniel Gewertz wrote about music, theater and movies for the Boston Herald, among other periodicals. More recently, he’s published personal essays, taught memoir writing, and participated in the local storytelling scene. In the 1970s, at Boston University, he was best known for his Elvis Presley imitation.

Tagged: Bob-Dylan, Larry Starr, Listening to Bob Dylan

I realised as a 14 year old in 1964 that Dylans songs were actually prose/poetry set to music. “Hollis Brown ” showed that. “Its Alright Ma”. ( Sometimes even the President of the United States must have to stand naked). “Bob Dylans 115th Dream”. Pathos, insightful politics, humour.

“Bringing It All Back Home” was the killer. Farewell to the folkies on one side, hello the new on the other. Then came “Highway 61”. Let’s not forget the great musicians be chose, especially Mike Bloomfield.

I saw Dylan here in Perth in Western Australia in 1966, I was fifteen and a half. Backed by the Hawks, minus Levon Helm. He had quit the world tour after the US leg of the tour, tired of the booing. My friend and I didn’t know we were watching what would become The Band. What a bonus.

First half was acoustic, Dylan played a couple of songs from the unreleased “Blonde on Blonde”, like “Visions of Johanna “. The audience loved it, little knowing it would be on “”Blonde on Blonde” in electric form! There was some booing in the second half. Some clown called out “Get on with it Bob” as Dylan fiddled with tuning his Fender. He replied ” They didn’t laugh at us in Ihio.”

Robbie Robertson was on fire, they were all stoned. Dylan slowly slid off his piano stool playing “Ballad of a Thin Man”. This was a life changing concert to a couple of 15 year olds. I would see Dylan another five or so times over the years. Once with Tom Petty. Once with Patti Smith.

That’s very close to the show I saw in Queens, NY in ’65, but the quartet had Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm, Harvey Brooks on bass and on electric piano, Al Kooper. I have a memory of “Gates of Eden” acoustic, and “Subterranean Homesick Blues” and “Maggie’s Farm” electric.

Bob Dylan–DYLAN, is just the bomb! So, yes, Fan Girl wants to read this book. We all come at life from differing perspects (perspectives), I LIKE to laugh at the jugglers and the clowns…for aren’t we, indeed, all…Yes, “All the World’s a Stage.”

Also great to see how well “Like a Rolling Stone” holds up to today’s idea of $250.00 ripped jeans. “You used to be so amused, At Napoleon in rags and the language that he used…” True ‘Grunge’ didn’t start out that way, did it? Nor did ‘Punk.’ America is full of great talents that never get a chance….Some like Dave Grohl and Elvis Costello get to eat more than peanut butter and jelly, pasta and sauce, others get to eat more widely, it’s sometimes the workings of Fate, or who you know, nothing to do with talent.

And re: ‘ Princesses on steeples’: our ideas and ideals of American Royalty… today, as in yesterday’s times, persons still feel the need to stick an expensive diamond in your face, “Hoo-boy, look at the size of that one!” I don’t mind diamonds, but never understood what the rukus was all about.

Love me some Dylan, and anyone able to step up to the plate and put their heart into writing a book (especially a nice short one) has got me vote. Nice review, though. Quite sincere and well written* – Anastasia (only kidding!*)

Complain about use of the obscure phrase “strophic form” with the use of the at least as obscure word “palaver!” Did you mean to do that??

A late reply: I am very clearly not complaining about the fact that “strophic form” is obscure. Several of the technical/academic words used in the book are obscure to the lay reader. I am complaining that strophic form — a term utilized in classical music — has absolutely no meaning in the pop music of the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries since the vast preponderance of songs — nearly all of them — have repeated lines or segments. It is hard to come up with songs that don’t repeat something or other! So, it is pretentious and nonsensical to use this phrase over and over. Dumb showing off. The word palaver, on the other hand, is appropriate, and not that uncommon. It’s just a good word. It means idle talk.