Film Review: Chronicle of a Movie Never Made – “Speer Goes to Hollywood”

By David D’Arcy

Albert Speer’s reputation as a “good Nazi” was the architect’s postwar monument. He spent as much time burnishing that brand after prison as he did when he was rising through the Nazi ranks.

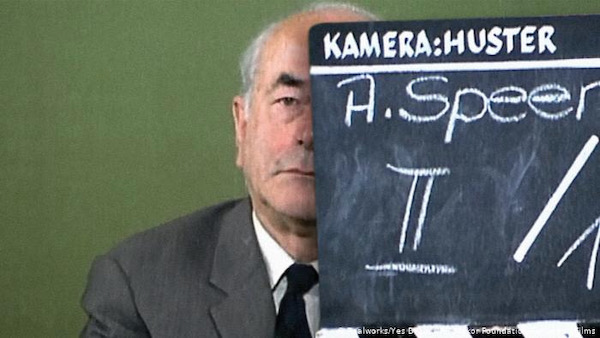

Speer Goes to Hollywood, directed by Vanessa Lapa.

A photo of Albert Speer in a car in Speer Goes to Hollywood.

The architect Albert Speer (1905-1981) redesigned Berlin as a monument to Hitler, who named him Armaments Minister of the Third Reich and put him in charge of Nazi arms manufacturing and supply. Speer managed war production through the forced work of millions of prisoners and slave laborers, yet in public seemed an urbane and restrained professional. It was a role that he revived when charged with war crimes at the Nuremberg Trials. It worked. He got 20 years, rather than a death sentence.

After Speer’s release in 1966, he published Inside the Third Reich and other memoirs that sold millions of copies in many languages. As before, Speer in his books seemed to be a reasonable, even apolitical, man. The memoirs sold because Speer had been as close to Hitler as anyone alive — like father and son, some said. Yet Speer claimed to have been unaware of the Holocaust and other Nazi atrocities.

No surprise, some saw a movie in all this, a Hollywood movie. Major studios were interested, especially Paramount. The screenwriter Andrew Birkin (The Lost Boys, The Name of the Rose, The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc), brother of actress Jane Birkin, wrote the first draft of a script. He and Speer reviewed it over the course of 40 hours of conversations in the winter of 1971. Stanley Kubrick was their first choice to direct. They also considered Costa Gavras. Birkin recorded their talks on audiocassettes.

The jumbled documentary Speer Goes to Hollywood, directed by the Belgian-Israeli Vanessa Lapa, presents itself as if it were taking us on a tour of that process, thanks to the original audio recordings. There are also actors voicing Speer, Birkin, director Carol Reed (The Third Man), and Birkin’s cousin, who offers Birkin ways to improve the screenplay. Reed comes across as the film’s conscience, warning repeatedly about a “whitewash.” The Hollywood movie for which Speer groomed his profile was never made. The recordings remind us that the courtly Speer remained, as he always was, ambitious and dissimulating about his monumental crimes. Speer wanted the movie to be neither a documentary nor “C.B. De Mille” epic, but something akin to “a modern painting … a van Gogh painting.”

You can learn a lot from Speer Goes to Hollywood, if you know things about its subject that the documentary doesn’t tell you. We see Speer’s designs for the German capital in Berlin, never constructed, which was to be renamed Germania. An ordinary architect, Speer excelled at logistics. As part of the demolition necessary for the construction of Germania, Jews were thrown out of their homes. They were either crowded into communal dwellings or shipped East. Asked by Birkin about the deportations of Jews, Speer responds by calling them “evacuations.” “You can’t keep the Jewish people in the middle of Germany,” he explains. He also admits that Hitler told him privately that he wanted to “annihilate” the Jews.

Speer and Birkin talk about Mauthausen, the horrific camp near Linz, where Hitler grew up, built around a quarry where stone for Germania and other Nazi projects was mined by prisoners who toiled until they died. It was not a secret; prisoners from the camp were loaned out to local farms and businesses. Speer says he didn’t know about mass killings there, although a prisoner who testified at Nuremberg identifies him as a Nazi official who visited the camp. The documentary does not tell you that, in 1944, the Nazis began transferring prisoners from Auschwitz and other camps to Mauthausen. Speer, who said he did not know about the site’s crematoria, would have known about any additional transports of slave labor. Speer tells Birkin that in 1944 he had 14 million laborers working for him. The figure may have been more like 12 million, but Speer was always promoting himself.

His reputation as a “good Nazi” was this architect’s postwar monument. He spent as much time burnishing that brand after prison as he did when he was a member of the Nazi party.

And so the interviews went, with Birkin, seemingly eager to please the war criminal, asking gingerly about one atrocity after another. When murder or war crimes come up, Speer doesn’t say much, often offering food or a drink in response. “Concentration camps had a bad reputation,” he tells Birkin, “It was known in Germany that a stay in a concentration camp was an unpleasant matter.”

Unpleasant indeed, for Speer. When details of the horrors of Mauthausen come up in the conversation, Speer, speaking like a publicist, asks Birkin to look for footage of another concentration camp, maybe the underground camp where slaves made the V-1 and V-2 rockets. Birkin suggests a compromise — using shots of Speer leaving Mauthausen before the film mentions atrocities, thereby giving the war criminal an alibi. Even Mel Brooks didn’t have an “I was driving in the other direction” joke.

The film has archival footage of silly Nazi home movies and Speer schmoozing with Hitler at his alpine retreat in Obersalzberg, There are also revealing juxtapositions — from the Nuremberg Trials — of the polished Speer alongside the Nazi minister of Labor, Fritz Sauckel (1894-1946), a short, bald, thick-necked man (wearing a Hitler mustache, even at the trial), who supplied Speer with slave workers. Sauckel was executed. Speer mentions on the tapes that he did write to Robert Jackson, the American prosecutor, warning that he couldn’t predict what he might say to the Russians if they ever got hold of him. It feels as if there is more to that story.

Speer Goes to Hollywood isn’t subtle filmmaking. Music becomes loud and heavy-handed at the wrong times, and the actors who stand in (speak in) for Speer, Birkin, and Reed sound and feel like performers. The one speaking for Speer speaks English faster than Speer ever did. Also, although Speer’s books still sell today, he’s not a household name. That means more context is necessary, especially facts, given that what context we get comes from Speer himself, who’s hardly a disinterested source.

A scene in Speer Goes to Hollywood.

Researching online and in published studies for more context on Speer, I found a letter from Andrew Birkin to a website that published a review of the doc in March 2020, after it premiered at the Berlin Festival. Birkin, who found much in the film commendable, noted that some crucial lines credited in the film to Speer were taken from his talks with other interviewers. According to Birkin, these lines were edited into the documentary (and read by actors) without making that distinction clear. If that’s the case, this is a film that begs for the release of the original tapes.

On a screen of text at the end of the film, we read that Paramount decided not to make a feature of Inside the Third Reich. Birkin writes in his response to the review of the film, however, that Paramount didn’t kill the deal, but Speer’s German publisher did, refusing to renew Paramount’s option unless the studio removed a scene that suggested Speer was present at a notorious November 1943 speech by SS chief Heinrich Himmler in the Polish city of Poznán (Posen) where he called for the extermination of the Jews. Even if Speer wasn’t present, it’s hard to imagine that he was unaware of such an important address and its effects on military logistics.

Finally, a scripted film was made. In 1982, ABC television broadcast a two-part film, Inside the Third Reich, with Rutger Hauer as Speer and with barely a mention of the Holocaust. Speer was co-credited as screenwriter.

In 2014 Vanessa Lapa released The Decent One, a documentary about Himmler that included the SS man’s love letters, discovered after the war. He expressed tenderness for his wife and daughter. (Himmler also fathered two children with a mistress.) Can a mass murderer have a soft side? If this one did, revealing it probably wouldn’t have swayed the judges at Nuremberg. But that Nazi never got to court. Himmler, responsible for millions of deaths, including those of children who never got sweet notes from him, took cyanide after he was captured trying to mix among German prisoners with the forged papers of a sergeant.

The Decent One suggests that people capable of mass murder can also be capable of tenderness. Speer, who plays with his dog and speaks lovingly of his wife, presents a different and more difficult problem. Here was an educated man who separated his job of organizing arms production in a world war from his complicity in the fate of those murdered making those arms — or using them. Yet the man who wanted to be seen as an effective guiltless technocrat owed his position in the Nazi leadership to his personal closeness to Hitler. After 20 years in prison, he cashed in on that relationship while swearing to the media that he never knew of the Nazis’ worst crimes. The movies were another step in that marketing campaign.

Speer died in London in 1981, where he had traveled to be interviewed for a BBC documentary.

Addendum: Birkin has gone on the record to point out that Lapa’s film takes liberties with the material he recorded, and the director has acknowledged to some journalists that the lines read by the actors are compressed from the conversation on Birkin’s tapes and incorporate material from other interviews.

David D’Arcy, who lives in New York, writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

This informative and incisive review is much appreciated. It does, however, put me in mind of another German aesthete who did get away with her complicity — Leni Riefenstahl.

Why not a spell at Spandau for her too?

As it happens the worst punishment Riefenstahl endured was a brilliant eassy by Susan Sontag — Fascinating Fascism.