Arts Reconsideration: The 1971 Project — Celebrating a Great Year in Film (Part Four)

Compiled by Bill Marx

Could this be a case of reviewer envy? After seeing the magazine’s music critics pay monthly homage to 1971 as a monumental year for music, the Arts Fuse‘s film critics immediately registered — en masse — their belief that 1971 was also a great year for film. And they demanded that they be given an opportunity to write about their favorites. What is an intimidated editor to do but give way to such eagerness? Below is the fourth effusion of enthusiasm for the best movies of that year.

I will point out from my editorial perch that the chosen films in this installment have a doomed romance lurking somewhere in their critiques of Vietnam, capitalism, technology, conformity, racism, and heterosexuality. Julie Christie’s opium-addict madam is fatefully wooed in Robert Altman’s anti-Western, a homosexual marries a nymphomaniac in The Music Lovers, love is an impossibility in THX 1138‘s totalitarian mélange, and the Australian outback remains beautifully neutral to the sexual urges of white and Black in Walkabout.

This was the last gasp of the rebellious artistic/political energy generated by the ’60s. The end of the Vietnam War in 1975 quelled the era’s mounting activism — there was no more draft. Soon forgotten were Martin Luther King’s challenges to the counterculture to end racism and create a more equitable economic system. Boomers worked their proto-neoliberal asses off to consume their way to a comfortable lifestyle, culminating in the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. So it is telling that the superb films selected for this series dramatize the downside of rebellion. 1971 gave us bursts of magnificent iconoclasm that had no future — culturally or politically.

Part One of “The 1971 Project — Celebrating a Great Year in Film”

Part Two of “The 1971 Project — Celebrating a Great Year in Film”

Part Three of “The 1971 Project — Celebrating a Great Year in Film”

— Bill Marx

McCabe & Mrs. Miller

Julie Christie and Warren Beatty in McCabe & Mrs. Miller.

A prime example of early-’70s chutzpah, Robert Altman’s alternative Western McCabe & Mrs. Miller unfurls across the screen like an American Brueghel. Tweaking the “carving a town from the wilderness” myth, it recounts the establishment of a whorehouse in a Northwestern settlement called Presbyterian Church.

The movie may be set in 1901, but it’s marbled with concerns of 1971. There’s a bobbing and weaving quality, signaling that the truth of a situation can’t be easily pinned down. This relativism reflects the loss of illusions in the era of Tricky Dick Nixon and the Vietnam War. Viewers are forced to find their footing as the filmmakers deliberately mess with the audience’s ability to see, because of a process used by cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond that mimics Daguerreotype photography, and to hear, because of overlapping dialogue that democratically includes bit players.

For this adaptation of an Edmund Naughton novel, Altman, co-screenwriter Brian McKay, and stars Warren Beatty and Julie Christie created something never quite seen in the genre; perhaps light on plot and action, McCabe is dense in atmosphere and eager to flip expectations.

Take the first meeting of the title characters. Gold-toothed gambler John McCabe has become the toast of the town by promising the bumpkins a pleasure dome. Steely-eyed Cockney pragmatist Constance Miller makes the long, muddy journey in to tell him all he doesn’t know about running a “proper sportin’ house”—and about women in general. She then wolfs down a plateful of eggs and stew with unladylike gusto. McCabe, flummoxed and convinced, makes her his partner.

Both leads (a couple at the time) give fine, nuanced performances. Beatty delights in the comedy of McCabe’s vulnerability as he woos the madam — with cash in hand — mumbling to himself about his romantic potential (“I got poetry in me”). Christie reveals Constance’s poignant duality: beneath the tough veneer, she’s a drug addict liable to slither away to the netherworld of an opium den. Still, it’s a pleasure to watch her eyes turn warm and twinkly, even if it’s a pipeful that caused the change. Will these two, who genuinely care for each other, ever get their feelings in sync?

The bordello — a site for vivid characterizations by the supporting cast — is up and thriving when two strangers propose a deal to buy out McCabe’s holdings. He bluffs, hoping for a better price, then finds out they were from a corporation that intends to control the town and doesn’t take no for an answer. On the heels of the negotiators come a trio of hitmen.

An act of senseless violence toward a sympathetic character changes the movie’s tone. McCabe realizes no one’s going to protect him — not the law, in the person of William Devane’s slick attorney who invokes the trust-busting of populist William Jennings Bryan, and certainly not God, represented by the surly, cowardly preacher.

Integral to McCabe are its songs by Leonard Cohen, from his 1967 debut album. Amazingly, they weren’t chosen before or during the shoot, but in postproduction. Altman later said perhaps he had absorbed the album and it influenced the film. The Stranger Song is the perfect theme for McCabe, as is Winter Lady for Mrs. Miller. Sisters of Mercy introduces us to the whores as they take a communal bath that’s more playful than prurient, and rapturous in its textures of wood, steam, and flesh.

— Betsy Sherman

The Music Lovers

Glenda Jackson and Richard Chamberlain in The Music Lovers.

The exact number eludes me, but I believe I’ve seen Ken Russell’s Film on Tchaikovsky and The Music Lovers (Hell of a title, isn’t it?) either 41 or 42 times – twice during its initial 1971 American release, at frequent repertory cinema screenings and, since buying the DVD in 2011, annually. It’s an audacious, emotionally overwrought, magnificently photographed (by Douglas Slocombe) piece of cinema, filled with lurid biographical details, intentionally over-the-top performances, a dark sense of humor, and plenty of the glorious music of Tchaikovsky.

But it’s not your traditional biopic. Screenwriter Melvyn Bragg, with an assist by Russell, freely fashioned an adaptation from Beloved Friend, a collection of the profuse correspondence between Tchaikovsky and his wealthy benefactor, Nadejda Von Meck. The script features pieces of dialogue right out of those letters, but it plays loosely with many events in Tchaikovsky’s life, resulting in a multilayered narrative that emerges as an interpretation rather than an accurate portrait. That’s part of what makes the film so much sordid fun.

It opens with an early example of what would become a Russell trait: an audience-grabbing jolt of visual energy. Cameras and people swoop through an exciting street fair in a wintry Moscow. Russell makes cinematic use of the scene in the same way a composer creates a prelude for a piece of music. To the accompaniment of a snatch from Tchaikovsky’s Suite No. 2 in C Major, he briefly introduces characters (motifs?) who will be developed as the story progresses. There’s Tchaikovsky (Richard Chamberlain), there’s his lover Chiluvsky (Christopher Gable), Tchaikovsky’s brother Modeste (Kenneth Colley), Madame Von Meck (Izabella Telezynska), Nina (Glenda Jackson) — the woman he would join in a doomed marriage — and others.

The film takes a quiet breath to note that homosexuality in late-19th-century Russia was a bad idea for people in the public arena, then launches into what remains a highlight of Russell’s career: a presentation of Tchaikovsky’s first performance of his Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-Flat Minor. It’s a dazzling, 15-minute, almost wordless mix of reality and fantasy — of Chamberlain magnificently finger-syncing (to a recording by Rafael Orozco) at the piano, while he and key audience members trip out to the music, their dreams flowing onto the screen, some in soft-focused idyllic settings, others morphing into the shape of a ballet, before it returns to Tchaikovsky’s frenzied keyboard work at the concerto’s conclusion.

The scene culminates in the film’s first brush with spot-on shameless overacting (which, considering the florid atmosphere surrounding it, never feels out of place) — Tchaikovsky, still a professor of music, being dressed down over the quality of his music by his boss, Nikolai Rubinstein (Max Adrian). From there, the drama never lets up, courtesy of characters including the misguided, tortured, and selfish Tchaikovsky; the lonely, desperate, sexually voracious Nina; the jealous, fragile Chiluvsky; the munificent but self-centered Von Meck; the list of lost souls goes on.

The plot point that stands out — indeed, the one that got the film its green light — is that of a homosexual marrying a nymphomaniac. But The Music Lovers also delves into suicide, madness, prostitution, rape, and life imitating art. It’s about an impulsive and reckless search for love, along with its complications and disappointments. There are moments of great beauty, of complete shock, and of utter revulsion … but don’t forget the dark humor. Both Chamberlain and Jackson pull out all the stops in bravura performances, leading the film up to its horrific, sad ending. I am physically and emotionally drained every time I watch it. But I think I’ll go for a second viewing before this year is out.

– Ed Symkus

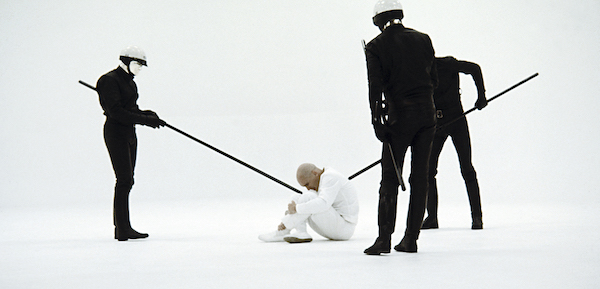

Techno-bullying in THX 1138.

THX 1138

It seems madness to think that the guy who made this thoughtful, nightmarish, biting social satire conflating totalitarianism, religion, and consumerism would go on to market Jar-Jar Binks dolls, but it’s undeniably and painfully true. Please note the film discussed here is the 1977 cut of the film (restored after its original 1971 release), and not the abominated “Director’s Cut” of 2004, that ruined the terrifying simplicity of Lucas’s original vision with garbage CGI.

THX 1138 is an art film. The work of a true auteur. It’s a film that doesn’t feel shot, so much as decoupaged, like a William S. Burroughs cut-up. It tells the story of a guy named (numbered?) THX 1138 who works in a factory assembling the fascist, android cops who suppress the society he lives in, literally building his own oppressors in a workplace where, sort of like in an Amazon warehouse, it’s OK for people to die, so long as quotas are met. Of course, in this world in which love is forbidden, he and his randomly assigned roommate fall in love, and pregnancy, jail, and a prison break follow.

But none of these plot points do justice to the oppressive feel of THX 1138. The film’s editing and sound design (by Walter Murch) keep the viewer in a cinematic state akin to Alvin Toffler’s head-spinning Future Shock. This is a broken world that requires our minds be broken to take it in. This is one of the few films set in the future that is truly futuristic in following the ideas of early-20th-century avant-garde thinkers like Marinetti, who in his “The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism” wrote: “Art, in fact, can be nothing but violence, cruelty, and injustice.” THX 1138 is all of those things, inflicted upon its characters, and (in a good way) upon its audience.

— Michael Marano

Walkabout

David Gulpilil, Jenny Agutter, and Luc Roeg cruising the outback in Walkabout.

Walkabout is the rare movie that refuses to feel dated. Not only do its astonishing visuals proffer the distinctively magical color palette and grain of ’70s celluloid, but its story and conflicts may be as relevant as ever.

Ostensibly, Walkabout is a coming-of-age story. The title refers to the Australian Aboriginal rite of passage in which adolescent boys are sent into the outback, responsible for their own survival. The twist here, carried over from the eponymous 1959 novel on which the film is based, is that we get two coming-of-age stories, one Indigenous and one Western. Foregrounded is the latter. A young British woman and her little brother are sent, unknowingly, into the unforgiving landscape after their father loses his mind while they are on a picnic. The two eventually meet an Aboriginal boy, who guides them through the outback, serving as their guardian angel. He makes finding water and foraging food look easy, in the process bringing his white acquaintances closer to the natural rhythms of the earth. Yet a deep chasm remains between the two cultures. The film’s brilliance lies in how director Nicholas Roeg visualizes this degrading “double vision.” (Editor’s note: Roeg and British playwright Edward Bond adapted the story from the novel; Bond wrote the screenplay.)

The Aboriginal has no real interest in the Western culture, though he is attracted to the pretty girl by his side. The girl, though she enjoys this departure from her privileged if mundane existence and the attentions of the boy, is never tempted to “go native.” (The film’s sexual imagery deserves its own commentary.). In one sequence, she is only wearing vestiges of her school uniform; she walks under a makeshift white parasol while the brown-skinned boy gracefully keeps his distance. The image effortlessly alludes to the history of colonialism and the casual indifference of the West.

Roeg’s intentions are never explicitly political. This is a fable about impossibility: no meaningful relationship can develop from what is a friendly pantomime. (In this light, the ending seems less shocking.) What’s most memorable is Roeg’s indelible vision of the outback, its ineffable beauty and overpowering menace. Terrence Malick probably watched this movie repeatedly before he filmed 1973’s Badlands, where he emulates Roeg’s dramatic zoom-ins on insects. The outback is Walkabout‘s protagonist, a pitiless metaphor for an indifferent world that recognizes no cultural chasms — only the need to persevere.

— Neil Giordano

Tagged: Betsy Sherman, Ed Symkus, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Michael Marano, Neil Giordano, THX 1138, The Music Lovers