Jazz Review and Perspective: Sheila Jordan’s “Comes Love”

By Steve Elman

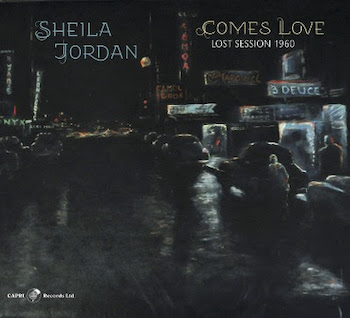

Comes Love was Sheila Jordan’s first full recording session as a leader, and it automatically becomes a collector’s item for those who love the legendary jazz singer’s work.

Sheila Jordan’s new recording ( Capri CD), a previously unreleased session from 1960, may be the earliest full document we will ever have of the development of her art.

Capri CD), a previously unreleased session from 1960, may be the earliest full document we will ever have of the development of her art.

Somewhere there may be radio air checks or wire recordings from Detroit in the late ’40s or early ’50s (when she was known as Jean Dawson), doing her first important work as part of Skeeter, Mitchell, and Jean. Somewhere there might even be an acetate of that trio of singers sitting in with Charlie Parker on the night he complimented her on her “million-dollar ears.”

But Comes Love was her first full recording session as a leader, and it automatically becomes a collector’s item for those who love Jordan’s work. It is more than that as well: a full picture of Jordan near the beginning of her professional career, offering telling insights into the ways she has grown as an artist.

Another plus: the last four tracks on the CD represent the only solo recordings of those tunes I have been able to find in Jordan’s discography. Three of them are gems, and for these alone, Jordan-lovers must have Comes Love.

There have been many cases of historic sessions coming to market posthumously, but this may be the first example ever of a seminal recording that has come back to life while the artist was still with us.

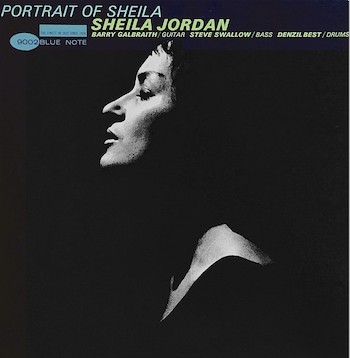

I assume you know who Sheila Jordan is. Anyone who loves jazz, and anyone who appreciates smart singing, should know of her and should know her recordings. Portrait of Sheila (Blue Note, 1963) had previously been considered her first session as a leader, but Comes Love predates it by two years. The recording has been buried for so long that Jordan’s biographer, Ellen Johnson, does not mention it in her otherwise definitive book, Jazz Child (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019). It has been buried for so long that no one (not even Jordan herself) knows for certain who is accompanying her.

But this is no tentative first-toe-in-the-water venture. Jordan had already been singing as an amateur and a professional for more than a decade, and Comes Love shows that, on June 10, 1960, she understood very well how to choose her repertoire and how to construct a set of rich and satisfying performances.

It might be worthwhile to reclaim the context of her life at that time to understand how remarkable this session is. It was 61 years ago, long before she was “rediscovered” in the ’70s and achieved the critical acclaim she had always deserved, long before she had become the Last Bebop Singer Standing, long before she was recognized as the unique and magnificent artist she remains today, looking forward to her 93rd birthday on November 18.

Back then, Sheila Jordan was 31, a single mother with a four-and-a half-year-old daughter, living in a tiny New York apartment.

She had come up in Detroit as Sheila Jeanette Dawson. She had been thunderstruck by Charlie Parker’s music when he played her hometown. That experience formed her musical thinking, just as it continues to inspire her now.

Of course, she knew she had to be in New York, so she moved there around 1952, sat in and gigged where she could, married Charlie Parker’s pianist Duke Jordan, and had a daughter named Tracey (Duke left her soon after the baby was born, more in love with heroin than with his new family, leaving her with his name and not much more).

She may have felt intimidated by the challenges of making it in the big city. In the notes to her first major-label LP, Portrait of Sheila, she is quoted: “I got scared. It was very important for me to sing, but it was too much of a rat race out there.”

She may have felt intimidated by the challenges of making it in the big city. In the notes to her first major-label LP, Portrait of Sheila, she is quoted: “I got scared. It was very important for me to sing, but it was too much of a rat race out there.”

But she also knew what she had to do, so she took a day job in an office to put food on the table, and fed her soul by working a couple of nights a week at a gay club called Page Three. A pianist named Johnny Knapp had the gig, and Knapp asked Jordan to join his trio, which was anchored by a drummer named Ziggy Willman. Occasionally, the bass chair was filled by a new guy in town named Steve Swallow.

Swallow discovered that he was working with someone special at Page Three. Ellen Johnson quotes him in Jazz Child: “The room fell still when she sang; everything stopped. I remember one night, just another Monday, and Sheila was singing, ‘I’m a Fool to Want You.’ I was playing along, focusing on playing the right note at the right time, when suddenly tears erupted from my eyes. That had never happened to me before…”

As an unknown singer in New York, Jordan knew she had to be something other than a pure bebopper. The Girl Singer of the time, no matter how sophisticated musically, was supposed to have a distinctive presence onstage, to have a professional persona.

Jordan’s approach to finding that persona for herself was uncompromising in its trueness. She once told me that she could never sing a song that didn’t have personal meaning for her, and this earliest session proves that she set that particular course very early on — in these recordings, she shows that she is already an excellent interpreter of lyrics as well as a superb musician. There is one false step, but that one clearly was a learning experience.

The Page Three band made another recording, reportedly two years later, in 1962. They cut only seven tunes in that session, but those tracks provide some clues to the personnel on Comes Love, because the personnel there have been definitely identified as Knapp, Swallow, and Willman. (That date was issued on LP as a bootleg in 1977, to Jordan’s intense displeasure, because she surely was not paid for it, and the record was padded out with a track with another singer and an instrumental. To make matters even worse, the piano had not been tuned and the recording quality was amateurish at best.)

The most important point of comparison between the two sessions is the opening track on Comes Love, “I’m the Girl.” This is an Other Woman song, the pathetic, resigned plaint of a woman who’s always there for her man, despite the fact that he loves someone else much more than her. Perhaps it was less culturally anachronistic in 1950, when James Shelton wrote it for a short-lived Broadway revue called Dance Me a Song. The lyric is painful to hear today, probably because Jordan does nothing to soften its hard edges. For comparison, listen to Jordan’s version alongside Roberta Flack’s on Killing Me Softly (Atlantic, 1973), where the harmonies are more comforting, and Flack omits the bitter coda (“I’m the one who’s second-best”) altogether. In Jordan’s version, she and the pianist take a hard rest and shift keys for a jarring dissonance on “second-best,” underlining the persona’s lack of self-respect.

The arrangement of “I’m the Girl” on Comes Love is identical to that on the bootleg, right down to the dark chords the pianist plays in the introduction and a late-night piano figure under “I am the one who will go.” Both touches are strong evidence that the pianist on both dates is Johnny Knapp. However, the bass part on the bootleg — despite being underrecorded — is more attuned to Jordan, and more musical, than the bass part on Comes Love, so regrettably, Steve Swallow is probably not playing bass on the new release. The bassist may be another of Jordan’s regular gigmates, Gene Perlman. The drummer is probably Willman.

Shelia Jordan in the early ’60s. Achival photo

Almost all the other tunes on Comes Love are compositions that Jordan has sung many times in the subsequent years, and comparing these early versions with the later ones is eye-opening. Here is a track-by-track rundown:

Second on the new CD is Ellington’s “It Don’t Mean a Thing.” Jordan does it in the original spirit of Ellington’s tune — as a throwaway, a fun song, 97 seconds of sass and speed. She recorded this on the bootleg session as well, and the arrangement on Comes Love is almost identical to the one on the bootleg, except that the newly released version is even shorter, jumping into the familiar melody with the briefest of intros. She takes three or four joyous risks as it speeds along, and she tosses in a beautiful high note that provides a big-smile surprise.

The tune has been in Jordan’s book ever since, and she revisited it in a duo recording with bassist Harvie Swartz in 2012 (Yesterdays, High Note). The sass and fun are still there, 52 years later, but Jordan’s voice is darker in the later recording, and somehow there is wisdom in it, too — “It really doesn’t mean a thing if it doesn’t have that swing … whoda thunk it?” Where the Comes Love version is crystalline, the later track is caramel.

Third up is another tune that must have gone over well at Page Three — “Ballad of the Sad Young Men” by Tommy Wolf and Fran Landesman, two of the smartest songwriters contributing to the Great American Songbook. The song has an edge of condescension; it looks down from a sophisticated height on the empty lives of “sad young men” who “drink up the night.” Jordan gives it a straight reading on Comes Love, using it primarily as a vehicle for musical interpretation and preserving the song’s sharp edges. Example: “Choking on their youth / trying to be brave / running from the truth” is a particularly bitter set of lines, and Jordan does not try to soften them.

When Jordan revisited the song in 1990 as a guest on a date led by pianist Goetz Tangerding (Jazztracks, Bhatki), she seemed to have more sympathy for the sad young men — perhaps, in the intervening three decades, she had seen her share of them and come to pity them a little more. The words are the same, but her tone has shifted — almost as if to say, “Who are we to judge?”

The title tune, “Comes Love,” feels a lot like “Baltimore Oriole,” a song that Jordan recorded two years later and has since become a trademark number for her. It could be a message song (“Nothing can be done when love comes along”), but Jordan skates above the message in 1960, taking the tune at a medium-bright tempo, winking at the listener, and offering some clever musical fillips, including some substitute melody on the reprise of the bridge and a lovely high note on “lose it right away.”

In 2008, Jordan recorded “Comes Love” again for her album Winter Sunshine (JustinTime). That version, from a live performance in Montreal, is a great example of the ways in which Jordan has enriched and expanded her interpretations of songs without losing the essences she first discovered in them. This one is much more expansive than the 1960 version, but in a similar tempo and with similar winks at the lyric. It has a bit of scat at the start. After she gives the lyric a witty read, she sets up a vamp, much as she did in miniature on her first recording of “Baltimore Oriole.” Here she uses the vamp to extend the groove of the tune and to invite some audience participation. The vamp occupies almost half the Montreal performance, including some biographical singspeak in Jordan’s completely personal stye (“Every guy I ever met / well, you know what they say, they were all wet”), along with some half-humorous exhortations to women in audience to give their partners a slap if they didn’t get some acknowledgment of Valentine’s Day. Both aspects of her sung monologue resonate with the theme of the lyric. She simply has opened up her original concept and brought her listeners along for the ride.

The “unfaithful man” theme of “I’m the Girl” returns on “Don’t Explain,” Billie Holiday’s classic. Wisely, Jordan doesn’t try to wring more pathos from the song than Holiday did, and her interpretation here is one of the highlights of the recording. She opts for musical shading to enrich the theme. The first time she sings the word “back,” in the phrase, “I’m glad you’re back,” she suddenly drops her pitch and then glisses up, a tiny musical illustration of depression dispelled by the lover’s return. She adds a high yelp of pain on “Yeah, I know you cheat.” Other aspects of this performance are simply superior musicianship — she knows you know the melody, and begins substituting her own melody right after she sings the first phrase. She caps this fine performance with a dramatic million-dollar-ears moment, reharmonizing the repeats of “Don’t explain” at the end.

Jordan recorded a duet version of “Don’t Explain” with bassist Arild Andersen in 1985 (Sheila, SteepleChase). In some ways, the later version is a straighter read, but with plenty of substance. Again, she stays away from hand-wringing and lets the music tell the story. The key is lower, to accommodate the changes that time has worked on her voice. “You’re my joy / you’re my pain” has much more weight in 1985 than the phrase did in her earlier version. And when she repeats the line, she adds “you’re my life, you’re my love” — you feel that you’re hearing the Voice of Experience. There are a couple of repeats of “Don’t explain” at the end of the tune, reflecting her original ideas 25 years earlier, but with less daring.

Shelia Jordan today. Photo: Janice Tsai

“A Sleepin’ Bee,” written by Harold Arlen, with lyrics by Truman Capote, is an odd song that jazz musicians have come to like, probably because of its unusual harmonic structure and idiosyncratic logic. At the time Jordan recorded it for Comes Love, it was just six years old. She sings it as an almost purely musical exercise, maybe because she recognized that trying to “interpret” a song about finding love by capturing a bee that won’t sting isn’t worth the trouble. Her work here is good-natured, with a substitute melody in the second chorus, and a harmonically surprising coda in rhythm.

In 1982, she came back to this tune in a duet album with bassist Harvie Swartz (Old Time Feeling, Muse). The approach was almost the same: a legato intro and a rhythmic middle section, beginning with “When a bee lies sleepin’,” using a substitute melody. In the later version, the coda is longer, and she returns to the legato feel of the introduction. The primary difference between the two performances is that she has even less regard for the lyric 22 years later, and has a lot more fun finding different melodies for the words.

“When the World Was Young” is the only complete failure on Comes Love. Jordan is simply too sunny a person to carry off Philippe Gérard and Johnny Mercer’s echt French conceit, in which a jaded sophisticate looks back with nostalgia on her earlier, sweeter days. She sings the “nostalgia” sections with lovely, ingenuous conviction, but she doesn’t sound like she could have lived a rich-enough life to be as bored as the “sophisticate” sections demand her to be. It concludes with a long, hugely daring glissando on the last word, and this too is a failure, because she doesn’t quite find the pitches needed to tell the listener where it’s going.

By the time she rerecorded the song, two years later on Portrait of Sheila, her approach had completely changed — and the later performance is a lesson in how brilliantly she understood what was wrong. In the notes to that LP, she describes how she chose to approach the song for its second recording: “I was kind of play-acting with myself, imagining what it would be like to be the belle of the ball, a party girl. I know I’m not, and yet it’s fun to fantasize.” That is, she had finally found a way to make the song meaningful to her, by making the entire performance a fantasy. The arrangement assists in this beautifully, making it a near-duet with guitarist Barry Galbraith, who was perfect at setting moods. All that it needs are a few choice bass notes and some subtle brushwork, and voilà, c’est merveilleux. And she preserves that tightrope glissando at the end, firming up the pitches and proving that it was a good idea that simply needed a little more work.

As I noted above, the CD is rounded out by four tunes that Jordan has not recorded elsewhere by herself, insofar as I have been able to determine. “I’ll Take Romance” is a song by the otherwise obscure Ben Oakland, with a fine lyric by Oscar Hammerstein II. Jordan takes this a bit too fast, which doesn’t give her the chance to really enjoy singing the words or to convey their meaning fully. It’s redeemed by another million-dollar-ears moment in the last few bars. This track is notable because pianist Johnny Knapp gets his only opportunity in the session to show off his chops, providing a very active accompaniment; I’ll bet that when the group played this at Page Three, he had the chance to take a couple of choruses with just bass and drums — something that would have balanced the performance here.

But then … ah. What a glorious, sensitive reading Jordan gives to “These Foolish Things.” This is one of the two minor masterpieces by English composer/singer Eric Maschwitz (the other is “A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square”), with elegant lyrics by Jack Strakey. Jordan sings it mostly straight, reaching deep into the lyric, but decorating the melody with tiny touches that are already her own and no one else’s. It is perfect.

But then … ah. What a glorious, sensitive reading Jordan gives to “These Foolish Things.” This is one of the two minor masterpieces by English composer/singer Eric Maschwitz (the other is “A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square”), with elegant lyrics by Jack Strakey. Jordan sings it mostly straight, reaching deep into the lyric, but decorating the melody with tiny touches that are already her own and no one else’s. It is perfect.

The only other time Jordan has visited this tune in a studio came in a 2021 session, where she appeared with Bob Dorough as one of two guest singers on Roseanna Vitro’s Sing a Song of Bird (Skyline). That performance is also gorgeous, for completely different reasons. Vitro decided to divvy up the lines of the lyric, and each singer makes the most of their contributions. Vitro leads off, giving the first A a smoky, sensitive, straight reading. Jordan takes the second A, and the contrast is immediate and revelatory. Even more than she did in 1960, she decorates nearly every word with a little pitch adjustment or a framing rest, never upstaging Vitro, but showing how confident she is in just being herself. Bob Dorough has the bridge in the first chorus and most of the last one; it’s a little sad to be reminded of his ineffably witty approach, and of the fact that he is another of Jordan’s contemporaries who did not live to sing in 2021.

Second-last on the CD is Richard Rodgers’s “Glad to Be Unhappy,” with a superb lyric by Lorenz Hart. This is Jordan in full song-interpretation mode, and she is sensational in her reserve and care. She includes the verse, with a gorgeous gliss on the word “sadly” that prefigures the theme of the song. Not that there aren’t moments of musical glory, too. She sings “And I’ve got it pretty bad” with clever half-steps down that are mirrored by Knapp on the piano, and then turns things around with little half-steps up on the “oh” of “oh so glad” in the last seconds.

Finally, it’s that terrific set-closer, the Gershwins’ “They Can’t Take That Away from Me.” And it’s just what you want — a full serving of Jordan, medium-up, in complete control, singing with an irrepressible smile and some magnificent musical somersaults executed perfectly — a complete line of substitute melody as the very first thing you hear, and yet another million-dollar-ears shift of pitch in the last seconds.

If you were sitting at Page Three in 1960, you’d clap and clap and beg her to come back for an encore. Fortunately, you can do just that on November 5, 2021, the next time Sheila Jordan comes to the area to sing at the Mad Monkfish, renewing her admirable partnership with pianist Yoko Miwa.

More:

Details about Sheila Jordan’s next Boston appearance from the Mad Monkfish website. The club is located at 524 Massachusetts Avenue, Central Square, Cambridge.

There are three more examples of early Jordan that are worth your attention — and one you can now safely ignore:

- In 1960, around the same time as Comes Love, she did a studio date with bassist Peter Ind, resulting in a beautiful one-off of “Yesterdays” that had previously been her earliest known recording (originally issued as part of Ind’s Looking Out [Wave, 1961]).

- We must not forget this masterpiece: in August 1962, she recorded an arrangement (a recomposition, really) of “You Are My Sunshine” that George Russell had written especially for her to show off those million-dollar ears. It eventually appeared on Russell’s The Outer View (Riverside, 1963)

- After Comes Love and these other first steps, in autumn 1962, she recorded Portrait of Sheila (Blue Note, 1963), including a deeply felt version of “I’m a Fool to Want You,” the song that had so moved Steve Swallow — who plays on the recording, along with guitarist Barry Galbraith and legendary bebop drummer Denzil Best. It was a critically acclaimed masterpiece, but it was the last LP issued under Jordan’s own name for more than a decade.

- As noted above, there was one more 1962 session, issued as a bootleg LP in 1977, as Sheila, on “Grapevine Records.” True fanatics (like this writer) wanted to own it despite Jordan’s scorn for it, but with the advent of Comes Love, there’s no longer any need to seek it out in the rare vinyl bins.

To hear Jordan speak about her work, including a reminiscence of Skeeter, Mitchell, and Jean, and to hear her sing with Steve Kuhn, the most sensitive pianist she has ever worked with, listen to this vintage radio show from the archives of NPR’s Piano Jazz, with host Jon Weber substituting for Marian McPartland.

Johnny Knapp died in 2018, and Atlanta magazine published this reminiscence, with many details about his career and a late-in-life photo — but no mention of Sheila Jordan.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, 13 years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

This is a great surprise! I’ve always loved Sheila Jordan, but I never knew much about her until today. Thanks for the great research piece.

I don’t understand the dismissal of the Grapevine record which is a completely different session with relatively good sound.