August Short Fuses – Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Film

White as Snow‘s on-screen fornications pile up, each more boring than the one before.

Lou de Laâge, left, and Isabelle Huppert in White as Snow. Photo: Cohen Media Group

As the title (White as Snow) kind of tells you, Anne Fontaine’s French-language film is a modern retelling of Snow White, though not a particularly necessary or arresting one. (The film opens at Kendall Square Cinema on August 27.) Isabelle Huppert goes slumming here as Maud, a scheming spa-owner and stepmother who, jealously, wishes the worst on her stepdaughter, Claire: Maud’s boyfriend lusts for the younger woman. Throughout the film, Maud’s homicidal attempts go awry, sometimes in a funny way, while Claire escapes to a rural haven in the Swiss Alps.

Lou de Laâge as Claire, the Snow White figure, is lusciously beautiful, with young Jane Fonda blue eyes, and every male she meets wants to bed her. That includes White as Snow’s equivalent of the seven dwarfs, seven geeky unmarried guys who live in the environs where she’s moved. Among them: a goofy cellist who is a hypochondriac about the health of his shaggy dog; an antique book dealer with off-putting masochistic desires.

Claire’s surprising reaction to this courting by a septet of nerds is that she happily mates with the majority of them, including a moody veterinarian and twin brothers. “Mountains set the blood boiling” is the explanation of the local priest, who passes no judgment on Claire’s randy behavior when she confesses it to him. So sleeping around is what she does, and if filmmaker Fontaine was a man she would certainly be accused of making a soft-core exploitation film. The on-screen fornications pile up, each more boring than the one before.

Meanwhile, Huppert’s stepmom comes looking for her stepdaughter brandishing weapons, such as a red-ripe apple which she fills with poison. It’s all pretty silly and campy. What can you say about a movie in which the most special moments are “B” unit shots of curving Alpine roads high in the mountains?

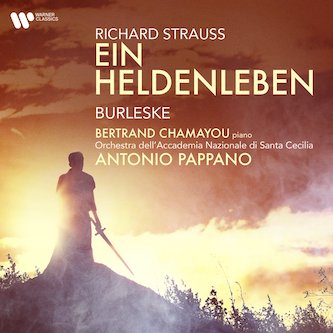

An essential documentary on the most important figure ever in American independent film distribution and exhibition.

A scene from Searching for Mr. Rugoff.

Who the hell was Donald Rugoff, dead at 62, buried in an obscure grave on Martha’s Vineyard? Ira Deutchman, a Columbia University professor and veteran himself of film distribution, makes a fairly airtight case in the excellent Searching for Mr. Rugoff (screening at Coolidge Corner Theatre from August 20) that his one-time boss is the most important figure ever in American independent film distribution and exhibition. In his heyday in the ’70s, Rugoff owned a string of jewel box movie houses on Manhattan’s East Side — the Beekman, the Sutton, the Paris, the twinned Cinema I and Cinema II — where New Yorkers saw the best of arthouse cinema distributed by Rugoff’s company, Cinema 5. We’re talking Ingmar Bergman, François Truffaut, Lina Wertmüller, also Mel Brooks, Monty Python, Woody Allen. Also weird movies like Andy Warhol’s Trash.

Rugoff operated like an East Coast Roger Corman, hiring young talent for his office fresh out of college, both male and female, giving them jobs of surprising responsibility and then working them to death. Someone described him as “an equal opportunity exploiter.” Like the future ogre Harvey Weinstein, he was abusive to everyone, hired and fired arbitrarily. Said one ex-employee, “Once you were in his employ, you were his slave.” And yet, there were all those great movies he got behind, and those wonderful theaters he built. And one difference from Weinstein: though he was a shitty husband and father, there is no case built in this film that Rugoff was a sexual abuser.

At the end of the ’70s, Rugoff’s empire crumbled. Kicked out of his company, increasingly dependent on drugs, he moved to Martha’s Vineyard with an enabler girlfriend. And was totally forgotten — there is no Wikipedia bio!– until this essential documentary. Now there is more than his Edgartown gravestone saying, “Donald S. Great Man.”

Arts Fuse interview with Ira Deutchman.

— Gerald Peary

Classical Music

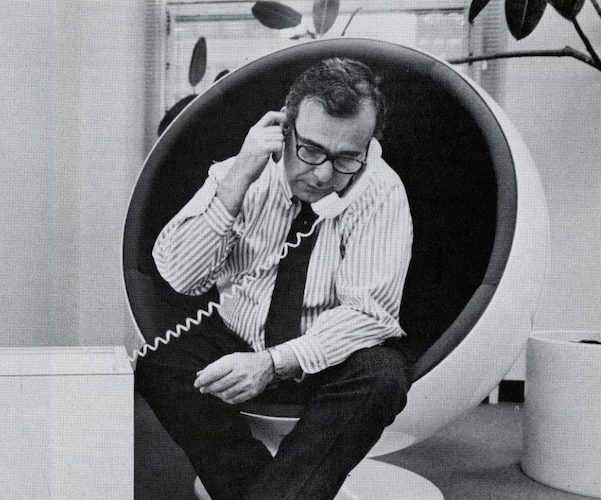

A superbly curated CD of lesser-known Romantic-era gems for organ, some with voice.

A fine performer can also be a superb curator. He or she puts together a coherent concert or CD of pieces that may be little known but that all deserve to be heard, and carefully arrays the pieces in a sequence that reveals the best traits of each piece.

A fine performer can also be a superb curator. He or she puts together a coherent concert or CD of pieces that may be little known but that all deserve to be heard, and carefully arrays the pieces in a sequence that reveals the best traits of each piece.

Robert James Stove — an organist and much-published music critic and scholar, based in Melbourne, Australia — here brings us his third lovingly curated CD. His first, The Gates of Vienna: Baroque Organ Music from the Habsburg Empire, consisted entirely of solo pieces, mostly from the 17th century. His second, which I praised here, was entitled Pax Britannica and brought to attention many (largely short) British works — again, for organ alone — from the Victorian era, including notable ones by Elgar, Stanford, and some lesser-knowns whose output I’d now like to know better, such as Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (whose father was a Black physician from Africa), Alfred Rawlings, and Ethel Smyth.

This third CD from Stove, French Romantic Church Music, centers on France during the long career of Alexandre Guilmant (1837-1911), a renowned organist and professor who became an international celebrity, playing recitals across Europe and North America. Stove gives us six lesser-known pieces by Guilmant, interspersed with similar “finds” from other French composers of his era, some of whom had studied with Guilmant, were close colleagues of his, or both. Familiar names (e.g., Saint-Saëns, d’Indy, Widor) alternate with ones that are less so (Bonnet, Cellier, Chauvet). Nine of the 22 pieces are world-premiere recordings; most of the pieces are for organ alone, but eight involve solo singers active in the Melbourne area.

I particularly enjoyed the inventive Carillon on Three Pitches by Gabriel Dupont, the touching Ave Maria settings by Widor (with soprano) and by Saint-Saëns (with mezzo), the rich harmonies of Vierne’s Préambule, and the “resourceful enharmonic side-winding” (as Stove’s fine booklet essay puts it) of Guilmant’s Absoute (i.e., “Absolution”). All the pieces earn their keep, in performances that are straightforward and clear, shapely in phrasing, and — when appropriate — rise to moments of passionate expressiveness.

French Romantic Church Music is available from the Ars Organi website or on Spotify and other streaming services. You can hear half-minute excerpts of each track here, and read Stove’s excellent booklet-essay here. All hail the performer-curator!

— Ralph P. Locke

Pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard brings this music blazingly, resoundingly to life.

You’re in good hands with Pierre-Laurent Aimard. The French pianist has technique to burn; what’s more, he’s one of the day’s most inquisitive interpreters. Rarely is any of his work pedestrian.

You’re in good hands with Pierre-Laurent Aimard. The French pianist has technique to burn; what’s more, he’s one of the day’s most inquisitive interpreters. Rarely is any of his work pedestrian.

So it is with this new pairing of Beethoven’s B-flat-major Piano Sonata no. 29 (Hammerklavier) and his op. 35 Eroica Variations.

In the Herculean Sonata, Aimard draws out much of the weirdness in Beethoven’s writing. His phrasings in the first movement oftentimes emphasize the music’s sense of struggle and invention. The pianist’s approach to the finale’s long introduction is fresh and improvisatory-sounding as they come. Beethoven’s contrapuntal writing in the outer movements speaks pertly; it’s also exceptionally well balanced and rhythmically snappy. The last is true, too, of Aimard’s playing in the expansive third movement, which grows in focus and intensity as it proceeds.

True, Aimard’s larger reading sometimes feels a bit expressively distant: it’s neither quite so warm nor flexible as, say, Steven Kovacevich’s or Daniel Barenboim’s (the second movement is tight but, emotionally, a bit subdued). Still, his thoughts on the Hammerklavier are well worth considering.

More personable is Aimard’s account of the Eroica Variations. There’s a palpable sense of joy to his illumination of the theme. The variations, be that the florid second, gamboling third, the quietly stormy sixth, swarming 12th, or pensive 14th, convey such a range of feeling, character, and sheer creativity that it’s impossible to look away.

In other words, Aimard brings this music blazingly, resoundingly to life.

Antonio Pappano’s new recording is no commonplace version of Richard Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben.

What happens when you replace the Germanic bombast of Richard Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben with Italianate warmth? You get Antonio Pappano’s new recording of the piece with the Orchestre dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia. True, one can’t totally forego Heldenleben’s euphuistic excesses. Still, Pappano’s is no commonplace Heldenleben: rather, it’s a performance overflowing with humanity, attention to musical detail, and natural feeling for the score’s theatrical structure.

What happens when you replace the Germanic bombast of Richard Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben with Italianate warmth? You get Antonio Pappano’s new recording of the piece with the Orchestre dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia. True, one can’t totally forego Heldenleben’s euphuistic excesses. Still, Pappano’s is no commonplace Heldenleben: rather, it’s a performance overflowing with humanity, attention to musical detail, and natural feeling for the score’s theatrical structure.

The introductory movements — “The Hero” and “The Hero’s Critics” — are well sculpted and characterful. So are Roberto Gonzales Monjas’s accounts of the big violin solos in “The Hero’s Companion” and “The Hero’s Escape from the World and Fulfilment.”

Pappano keeps everything moving smartly and cleanly, most impressively during the wild battle sequence: here, all the busy on- and off-stage parts are carefully balanced; each can be heard (including the woodwinds) as the music drives to its furious zenith.

“The Hero’s Works of Peace” is reflectively sung, while the solo violin’s hymn-like refrain in the finale (and the orchestra’s shuddering responses) resolve in an utterly cathartic coda. Truly, this is a beautifully planned and executed Heldenleben.

Also winning is the performance of Strauss’s Burleske that follows.

Pianist Bertrand Chamayou has all the notes in hand. His account of the solo part is thoughtfully sculpted, well voiced, and bitingly precise. The bold contrasts between the piece’s feroce and tranquillo sections impress; so does Chamayou’s grasp of the music’s dancing impetus.

Pappano and Co. are with him every step of the way, playing with identical purpose and vigor.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Jazz

Vocalist Lillias White’s voice combines Aretha Franklin-influenced gospel and sass with a certain showbizzy fizz.

The album’s theme is simple and free of patronizing irony, even though the sentiment might go against the grain of African-American culture at the moment. White means it, and she sells it convincingly in each track: Forget your troubles, come on get happy! You got to accentuate the positive, eliminate the negative!

The album’s theme is simple and free of patronizing irony, even though the sentiment might go against the grain of African-American culture at the moment. White means it, and she sells it convincingly in each track: Forget your troubles, come on get happy! You got to accentuate the positive, eliminate the negative!

The songs are short, and there are no solos. The foundation here is Cabaret as much as R&B, as you’d expect from a Broadway pro. White’s voice combines Aretha Franklin–influenced gospel and sass with a certain showbizzy fizz. If you don’t expect more from the music than what it’s trying to be, it’s all great entertainment.

Where the album really excels is in the choice of material. There are a few predictable standards, such as “Make Someone Happy,” “Get Happy,” and “Put On a Happy Face,” although each one is given a fresh arrangement and sung with conviction. “Get Happy” is unexpectedly a ballad. The simple, appealing piano vamp dims the lights. The contrast between the music and the lyric offers an alternative to the usual hyper cheerfulness — we are given a deeper and more thoughtful contentment.

Best of all are the imaginative takes on Queen’s “You’re My Best Friend,” Blood Sweat & Tears’ “You’ve Made Me So Very Happy,” and The Turtles’ “Happy Together.” Why hasn’t anyone else thought of “You’re My Best Friend” as an acoustic ballad? Hearing it in a jazzy context, stripped of the stiffness and bombast of Queen’s original, brings out the tune’s lovely melody and sensitive lyrics. “Happy Together” is also done as a ballad, which calls attention to tricky intervals that White handles with ease. “You’ve Made Me So Very Happy” is a fairly straight cover, but White’s theatrical instincts dig out the drama and strong emotion hiding in the song.

White is ebullient and glowing in all of the album photos. Let your guard down and let her give you that big musical hug.

— Allen Michie

A well-recorded collection of elegant meditations inspired by the pianist’s process of grief and recovery.

This album of eight elegiac pieces for solo piano is a recording that its creator, pianist Falkner Evans, never planned to make. It started in tragedy. On May 19, 2020, after long struggles with depression worsened by the Covid lockdown, Evan’s beloved wife, Linda, took her life. She was an artist and a teacher. The pair had been together for 30 years — decades of talking about art, travel, and other excitements.

This album of eight elegiac pieces for solo piano is a recording that its creator, pianist Falkner Evans, never planned to make. It started in tragedy. On May 19, 2020, after long struggles with depression worsened by the Covid lockdown, Evan’s beloved wife, Linda, took her life. She was an artist and a teacher. The pair had been together for 30 years — decades of talking about art, travel, and other excitements.

Evans got away from his apartment by moving in — for a week — with his brother-in-law. After not playing piano for three months, he found himself poking at a grossly inadequate instrument. The first three pieces found here, beginning with “Invisible Words,” were first created then. The title comes from a note Linda left: “Music is the invisible word, made visible through sound.” (The original quotation had music as the invisible world.)

The notion of making something visible, or perhaps palpable, recurs: the album includes a piece entitled “Made Visible” and it finishes with a version of the same theme, this time called “Invisible Words for Linda.” Obviously, making this music was a form of therapy for Evans. Interestingly he bases a number of the tracks on something his therapist told him — he needs to “breathe,” but, after his trauma, he will be breathing “altered air.” “Breathing Altered Air” is a stately piece. Like the others, its melody seems to be based on a short series of repeated chords — they serve as a kind of resting place amid the musings. If the collection has a fault, it lies in the pianist’s adherence to similar tempos. “Lucia’s Happy Heart” moves a bit more than the other tunes. Its textures are less thick, but one hardly hears joy in it. The composition was written in 2006. Linda had Italian forebears and wished she was named Lucia. Joy. Of course, elation is not the point of this collection, which is a well-recorded collection of elegant meditations inspired by the pianist’s process of grief and recovery.

— Michael Ullman

A disc of his previously unheard compositions not only gives Arni Cheatham, long hailed as a Boston music and arts education “hero,” his due as a continuing presence on the local cultural scene, but it also offers a fresh opportunity to appreciate the Boston jazz scene’s many fine players. The 70-something icon and his group of talented friends really got something going with this one.

A disc of his previously unheard compositions not only gives Arni Cheatham, long hailed as a Boston music and arts education “hero,” his due as a continuing presence on the local cultural scene, but it also offers a fresh opportunity to appreciate the Boston jazz scene’s many fine players. The 70-something icon and his group of talented friends really got something going with this one.

Not the usual quickly assembled jazz tribute, the music on The Sound of Dreams: The Arni Cheatham Project (Mandorla Music) intriguingly surveys post-bop era avenues that offer plenty of space for extended soloing. One can sense a lot of collective energy went into these recordings.

The disc features Hub stalwarts Kevin Harris (keyboards and arrangements), Jason Palmer (trumpet & flugelhorn), Gregory Groover Jr. (tenor sax), Andy Voelker (alto & soprano sax), Bill Lowe (trombone), Max Ridley (bass), and Tyson Jackson (drums). Cheatham himself appears on soprano sax on one track.

A longtime member of the fabled Aardvark Orchestra, Cheatham writes in the notes that many of the musical ideas revealed on this disc were inspired by his dreams. Indeed, “For Michael,” the first cut on the album, infuses its twists and turns a sort of surreal logic. The piece assembles a variety of directions into a tantalizingly elusive whole. A Groover (great musician name) tenor sax solo adds a surge of power to a work that brings out a “Wait, let me hear that again” response in this listener.

“Ordinary Man” puts an effectively fleet alto sax solo from Voelker on top of a hard swinging bottom, while “Raindrops/Teardrops” plugs a sensitive Palmer solo into its lilt. A bass interlude from Ridley captivates as well.

“Circular Mabel” gets all funky with Harris’s electric piano out in front and veteran Lowe’s muted trombone telling us about the lady in question. “Pink Birds” includes nice horn section work against a hard-charging modal foundation. Voelker and Palmer also shine here individually.

Drummer Jackson sets the breezy beat on “Sunshine Samba,” a piece that has Cheatham’s alto spinning out lazy afternoon stories designed to mellow us all out.

This fine album is probably the best tribute to Cheatham’s art because the music stands up so beautifully on its own — the fact that it pays due homage to the composer’s illustrious history is icing on the cake.

— Steve Feeney

Books

The impossibility of the imposition of the “two-state” solution has become abundantly clear, so what is the Jewish left in America and Israel going to do? At the moment, clinging to a comforting delusion reigns. Lip service continues to be paid to the Oslo scheme as a viable solution for the legitimate claims of the Palestinian population, which will soon be a majority. For conservatives, the anachronistic dream serves a useful purpose, part of a strategy to mask its continued movement toward the transformation of the Jewish state into an apartheid with a “human face,” including intimations of plans for ethnic cleansing. For liberals, propping up the “two-state” option allows them to ignore (or continue to rationalize) their role in helping to shape a catastrophic future — a separatism whose barbarism is the price for maintaining the contradiction-beset Jewish democracy. The latter concept, according to Omri Boehm in Haifa Republic: A Democratic Future for Israel (New York Review Books, 200 pages, $24.95), amounts to “government of the Jews, by the Jews, and for the Jews.” “By refusing to rethink the relation between Israel and Zionism,” he proclaims in his brave and sleek polemic, “liberal intellectuals have allowed the conversation about the country’s future to decline into a shouting match between chauvinistic Zionism on the right and anti-Israeli critique on the anti-Zionist left.”

A professor of philosophy at the New School for Social Research, Boehm argues for a radical shift in the way liberals conceive of Israel’s future. The “two state” solution is dead: time to agitate for a rational response to prejudice driven by militarism and the repression of past crimes against the Palestinians: the left must begin to argue for “securing a democratic homeland in which Jewish citizens exercise national self-determination — alongside Palestinian compatriots doing the same — in a joint, sovereign state.” No doubt there will be dissenters, but Boehm makes a stimulating case for the fact that Zionism’s fathers (including Menachem Begin!) would have agreed with Israel being “a joint, sovereign state.” Haifa Republic explores how that approach was undercut by the (political) weaponizing of the Holocaust, the power plays of the British and other international players, and the acceptance, by the right and the left, that Israel must be a religious homeland rather than a secular nation with respect for all. Along the way, Boehm justly points out the reactionary machinations of the usual suspects on the right, such as Benjamin Netanyahu and Sheldon Adelson, but he also punctures the double-think about Zionism practiced by “human rights” advocates, including Amos Oz, David Grossman, and Elie Wiesel.

Boehm’s agile blade, swung in the cause of recognizing reality, cuts both ways, and that lends his book its persuasiveness. What’s more, he offers signs of optimism, seeing in the recent rise in Israel of the Joint List party, which is supported by Arabs and Jews, “a bridge to a binational project independent of ethnic identity, one that will take us beyond the alleged necessity of separation.” At the very least, Haifa Republic introduces some stimulatingly radical ideas into what has become an inert conversation on the left: “a liberal Zionist political alternative can only emerge through an organic joint politics of Palestinian Israelis and Jews.”

— Bill Marx

Dance

Casey Howes in Endure. Photo: Richard Termine.

Endure: Run Woman Show, performed in Central Park, Manhattan. (Closed). Created, written, and co-produced by Melanie Jones. Directed and co-produced by Suchan Vodoor. Performed by Casey Howes.

On a balmy Saturday afternoon our audience of 15, like a secret society, assembled in New York’s Central Park for a performance of Endure, Melanie Jones’ sremarkable play. Warmly greeted by the production team, we banded together as we learned to operate old school iPods. Nothing fancy — just a pair of running shoes, a pocket for the iPod, and the will to keep up with a marathoner in training.

And keep up we did, without objection. Many of us would have followed the play’s star, Casey Howes, anywhere. In fact, Howes had us at her first gesture: a gentle but unequivocal shoulder tap that advised director Suchan Vodoor that he should take a backseat. Like the perfectionist marathoner she plays in Endure, Howes was determined to prove her worth as she sprinted throughout the park, suggesting the depths of her character’s anxiety and despair as she went along.

Howes’s movements ranged from razor sharp gestures and isolations to the unexpected grand battlement. Many walking through the park stopped to watch as she danced atop small boulders or hung from trees. Whether running, dancing, or standing still, Howes evoked the emotional extremes many of us have felt in this era of Covid. I would bet that she’s the first to perform chassés tours on grass.

As we watched Howes’s every move and, from time to time, searched for her as she raced ahead, we listened through our ear buds to writer Jones describe a life of self-doubt that leads to a problematic quest for perfection. She’s jealous of sisters, friends, anyone who might beat her to the finish line. She’s also impulsive: getting drunk before a training session does not impress one’s coach. Worse, this behavior leads to the dry heaves. We hear of her premarathon life, in which a seven-year marriage edged her toward suicide.

Jones does not offer a triumphant ending. This is not a feel-good sports story. Instead, we experience the healing power of running. Of course, endorphins are great, but the best part of this journey comes near the end, when our marathoner, instead of racing past a fellow competitor who has been injured and is writhing in pain, stops to offer aid. When she sets off again, we follow Howes to the Great Lawn, where she joins a sea of humanity. This final vista reminded me, as I strained to keep Howes in sight, of Doris Humphreys’ masterpiece, A Day on Earth. Do all great works of art extol the importance of community over individual triumph?

— Mary Paula Hunter

Sandra Oh in The Chair. Photo: Eliza Morse/Netflix

Streamed Netflix’s The Chair today.

First off, it’s very watchable. I can even get past the reduction of today’s student left to cultish conformism. Beyond that, I can even see some of my youthful leftism in that way. But I would add that some things are worth the risks of group-think. Was it cultish conformism alone that motivated a huge antiwar movement that was one significant reason among many that the United States withdrew from Vietnam? Were the chants: “Bring the Troops Home” and “Hell No We Won’t Go” signs of hysteria? I don’t think so.

What the students are ranting about in The Chair is less immediate, more ideological, and sometimes misinformed and even sit-com ridiculous. A main character of the series is seen trying to depict fascism to his class by goose-stepping and giving the Nazi salute. He’s videoed doing this and it becomes click bait, leading to accusations and complications that are the core of the plot.

So there’s room to pause on the question about new media: what would the ’60s and ’70s have been like had smart phones been present in every classroom, every demonstration, every argument, every confrontation?

A problem, too, is that few to none of the radicals, so quick to denounce their university as nothing but an institution of white supremacy, are seen maturing intellectually, are seen thinking, even amongst themselves. Who are these kids? What has predisposed them from the get-go to despise the prestigious institution — Pembroke University, depicted as a lesser Ivy — to which they have gained access?

But the series compensates in its own way for such lapses. Sandra Oh delivers a strong lead performance and she is a pleasure to watch. There are moments when the performer is as wild and eloquent as ever. Her character has been named the first minority head of Pembroke’s English department. She wonders if she was awarded that title at a particularly perilous time: the department and the university are about to implode.

For the first time that I know of (she often plays someone Chinese), Oh brings a lot of her Korean background and its stresses to this series. For example, there’s her grandfather, a Korean elder who has never managed to learn English. When he’s assigned by Oh to care for her daughter, tensions arise: the kid and the grandfather have no common language. And the kid, for reasons that deserve more attention, is quite the little brat.

So, despite its flaws and in no small part because of them, The Chair is worth a watch.

— Harvey Blume

Tagged: Antonio Pappano, Arni Cheatham, Ars Organi, Falkner Evans, French Romantic Church Music, Get Yourself Some Happy!, Invisible Words, Isabelle Huppert, Lillias White, Lou de Laâge, Mandalora Music, Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Robert James Stove, The Sound of Dreams

Both opposition to the war in Vietnam and support for the rights and aspirations of the Palestinian people are far more deeply and humanely based than some sitcoms and academic apologists are willing to acknowledge.

Welcome to the ongoing argument. I’m glad to see you post an opinion but it seems to me, a grizzled veteran of these discussions, that Haifa Republic, at least as you describe it, offers less in the way of new hope than you proclaim. In fact, what it seems to do is provide an argument for liberal Zionism, which is fine with me since it is how I engage with these arguments. But liberal Zionism is portrayed by both by left anti-Zionists and right wing Zionists as but a fantasy whose day is past.

But back to your review. You write that:

Boehm makes a stimulating case for the fact that Zionism’s fathers (including Menachem Begin) would have agreed with Israel being “a joint, sovereign state.”

Yes, Begin would have agreed about Israel being a sovereign state, but “joint?” This is nothing less than joltingly ignorant. Begin encouraged settlement on West Bank land, the more the merrier. And his mentor, Vladmir Jabotinsky, argued forcefully that a new Israel would need to build an “Iron Wall” against Arabs who would only respect an Israeli entity if they were forced to. Jabotinsky thought he was according respect to natural Arab ambitions by saying they needed to be defeated utterly, if Israel were to survive.

But I have some questions. For instance about the double-think about Zionism practiced by “human rights” advocates, including Amos Oz, David Grossman, and Elie Wiesel.

Leaving Wiesel out of it, what double think are you accusing Amos Oz and Grossman of? Please say, if you can.

Haifa Republic is a good name for a book offering new thinking about the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, Haifa being somewhat removed from the worst of it. But if the book really offers new thinking and anything like new hope about this conflict your review fails to indicate any such thing.

A short review is not about entering an argument. I simply wanted to recommend a brave attempt that faces reality and challenges those who don’t want to further apartheid and ethnic cleansing in Israel. The two-state solution is an illusion that is being (opportunistically in some cases) clung to by liberal intellectuals. Now what? “It is long time past for liberal Zionist thinkers to think again,” Boehm usefully points out. Haifa Republic articulates “an alternative to two-state politics from within a liberal Zionist perspective.”

Calling a assertion in a book you haven’t read “joltingly ignorant,” based only on a quick reference in a short review, is symptomatic of the knee-jerk responses Boehm sees as contributing to the current intellectual/political paralysis. Haifa Republic is only 166 pages — read it and then grumble. It has the merit of looking at a looming catastrophe in the face.

I am not accusing Oz and Grossman of “double think” — Boehm does. Here is a longish passage about Oz in his book. It gives you the flavor of his critique:

As for hope, there is this, “the international community would do well to start recognizing that a joint Arab-Jewish politics is the only model (Boehm’s itals, not mine) for a democratic future in Israel — and the only model that propels the country beyond the two-state solution. It is time to start lending this nascent politics legitimacy and support.” I am not an expert on Israeli politics, but Boehm points out some electoral results and parties (JOINT LIST) that are going in fruitful directions regarding a joint Arab-Jewish politics. Sounds interesting …. or have I been “brainwashed’?

Attention: For those interested in hearing Omri Boehm on Haifa Republic:

A Q & A sponsored by the Community Bookstore in Brooklyn

NYRB: Omri Boehm presents Haifa Republic, with Susie Linfield

August 26, 2021, 7:30 p.m.

Omri Boehm joins us to present his new book Haifa Republic: a Democratic Future for Israel, in conversation with Susie Linfield. This program is presented in partnership with our friends at New York Review Books and Congregation Beth Elohim, and will take place on Zoom. Register here:

https://www.communitybookstore.net/nyrb-omri-boehm