Opera Album Review: Up There with Handel and Vivaldi — One of Gluck’s Earliest Operas, in Its First-Ever Recording

By Ralph P Locke

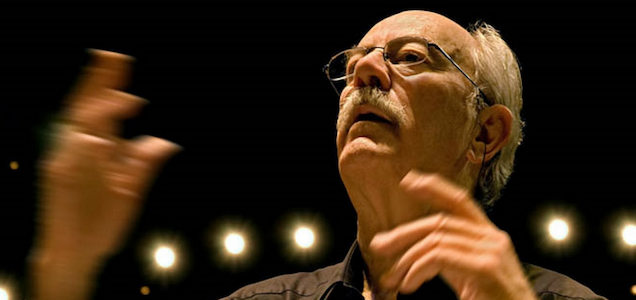

This world-premiere recording of Gluck’s Demofoonte is stylishly performed, under the experienced hand(s) of conductor/harpsichordist Alan Curtis.

Christoph Willibald von Gluck: Demofoonte

Ann Hallenberg (Princess Creusa), Sylvia Schwartz (Dircea), Romina Basso (Cherinto), Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen (Timante), Colin Balzer (Demofoonte), Vittorio Prato (Matusio).

Complesso Barocco, conducted from the keyboard by Alan Curtis.

Brilliant 95283 [3 CDs] 212 minutes. To purchase, click here.

I mostly forget that Gluck wrote lots of Italian operas in the manner of the typical opera seria of his day, consisting mainly of a long series of da capo arias (i.e., in ABA form). Music historians have emphasized instead his reform operas of the 1760s and onward, which often condensed the plot and broke down the boundaries between aria and recitative. Gluckian reform is familiar to opera lovers today, especially from his Orfeo ed Euridice and from the famous preface to Alceste. Gluck’s move from Vienna to Paris (with its highly developed and varied theatrical traditions) impelled him to even further experiments and departures, as in his two Iphigenia operas.

I mostly forget that Gluck wrote lots of Italian operas in the manner of the typical opera seria of his day, consisting mainly of a long series of da capo arias (i.e., in ABA form). Music historians have emphasized instead his reform operas of the 1760s and onward, which often condensed the plot and broke down the boundaries between aria and recitative. Gluckian reform is familiar to opera lovers today, especially from his Orfeo ed Euridice and from the famous preface to Alceste. Gluck’s move from Vienna to Paris (with its highly developed and varied theatrical traditions) impelled him to even further experiments and departures, as in his two Iphigenia operas.

So it was with surprise that I started listening, somewhat blind, to Demofoonte, only to discover that the work is cut from more or less the same cloth as the high Baroque opere serie of Handel, Vivaldi, Telemann, Hasse, and Vinci that I have reviewed for The Arts Fuse and in America Record Guide in the past few years. Which means that we encounter one largely treasurable aria after another, full of sweetness (as in the lapping waves of Timante’s delicate first aria, “Sperai vicino al lido”) or vigor (as in the title character’s “Odo il suono de’ queruli accenti,” with its wonderful intrusions by pairs of horns and oboes).

This is no surprise, for, as I learned when I interrupted my listening to read the informative booklet-essay by the noted musicologist Paologiovanni Maione and then did some further reading, Demofoonte was one of the first of some sixteen operas that Gluck wrote between 1741 and 1752 for theaters in Italy, Vienna, Prague, and London, and the earliest that has been largely preserved. (The surviving sources lack the overture and the recitatives; these were all composed for the 2014 production that we hear on this recording by its conductor, Alan Curtis. The recording is available on Spotify and other streaming services. The beginning of each track can be heard here.)

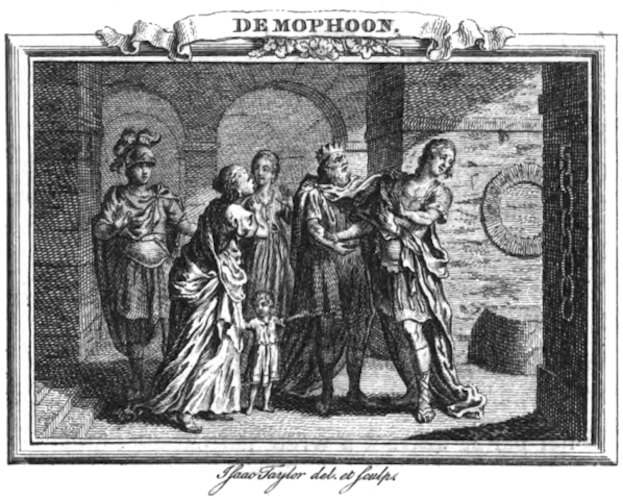

The great librettist Metastasio penned Demofoonte in Vienna, where it was set by Caldara for the nameday of Emperor Charles VI in 1733. It was set more often than all but three of Metastasio’s dozens of libretti. Niccolo Jommelli set it more than once! Cherubini would, decades later, set a French adaptation that larded the well-filled tale with yet one more sub-plot.

Gluck’s setting, for Milan (first performances: January 1743), was greeted with “widespread satisfaction and applause from the good numbers of spectators who attended each evening” (according to the Gazzetta di Milano). There was particular praise for the great castrato Giovanni Carestini, in the role of Timante, a man designated to marry Creusa (Princess of Phrygia) but secretly married to Dircea. Indeed, the musical inspiration and craftsmanship are so high throughout this work that I was delighted to keep listening (and putting other less pleasant tasks off!). I was particularly enchanted by the duet for Timante and Dircea that ends Act 2. (The track list here gives first the name of the character who actually enters second. Such an error is all the more annoying, given that all but two of the cast members sing in the soprano or alto range and so can be easily confused by ear.)

The late Alan Curtis, conducting. Photo: Limelight Magazine.

The singers are all notably fine (as indeed is the sharply profiled, two-dozen-strong Complesso Barocco). My one complaint is that the countertenor, a singer with a seductively gentle tone, is often weak on his lowest notes, his trill is soggy, and Curtis’s swift tempos stress him in some passages of coloratura (as in the middle section of his aforementioned first aria). Surely Carestini had more fire. But I don’t mean to complain too much: the countertenor in question, Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen, was a mere 20 years old and a Princeton undergraduate when this recording was made, and already quite artful and intelligent. Three years later, he would win the Metropolitan Opera National Auditions and be hailed in the New York Times as a “complete artist” with “a remarkable gift for intimate communication”. A more fully mature ANC — that’s the colophon on his website — can be heard as David in Nicholas McGegan’s 2019 recording of Handel’s Saul (available through streaming or download) and in a CD of arias by Handel, Vivaldi, and Gluck. (For details, see ANC’s website.) Still, I would love to hear this role — the work’s primo uomo — sung by a female singer whose range matched the part comfortably.

I complained a bit about Vittorio Prato’s weak low register and huffy coloratura in my review of Bellini’s Bianca e Gernando. Here he seems more comfortable. Colin Balzer is a lovely lyric tenor, best known for recordings of German art songs. He does a fine job with the often-placid title role of the king of Thrace. Rulers in Baroque operas tend to be noble and generous, thus less vivid than various of their scheming, hyperactive, or suffering subjects. Fortunately, Demofoonte does several times get a chance to rage aloud, as in his “Perfidi! Già che in vita.” Balzer’s healthy vocal production makes the sparks fly.

Illustration of a scene from Demofoonte, from an English translation of Metastasio’s libretto by John Hoole (published 1767). Photo: Wiki Common.

Best of all are the women: Ann Hallenberg (from Sweden), Sylvia Schwartz (from Spain), and Romina Basso (from Italy). I don’t recall ever hearing more expert early-music singing: each maintains a solid core of tone while giving appropriate weight to the message of the words. In aria after aria, I felt as if I were attending a master class in intelligent, multifaceted operatic interpretation. I was particularly taken with the embellishments eloquently delivered by Romina Basso in Cherinto’s “Nel tuo dono io veggo assai.”

So we can finally hear Gluck’s Demofoonte and revel in its energy and grace, in a generally superlative performance, one of the last efforts of keyboardist and conductor Alan Curtis before his death in 2015. The recording was made in a studio, days before a concert performance in Vienna with most of the same singers. Everything can be clearly heard, in beautiful balance.

It is unfortunate that Curtis did not live to supervise the recording’s (belated) release. He would have made sure that the libretto, which is available online, was issued in parallel columns, instead of as dozens of pages of English followed by dozens of pages of Italian. Who makes these decisions at the record company misnamed Brilliant?

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Alan Curtis, Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen, Brilliant Records, Christoph Willibald von Gluck, Complesso Barocco, Demofoonte