Book Review: The Woman Behind “All-of-a-Kind Family” — A Remarkable Legacy

By Cyrisse Jaffee

Biographer June Cummins considers the first All-of-a-Kind Family book, published in 1951, as groundbreaking and Sydney Taylor as “one of the first writers of multicultural literature for children.”

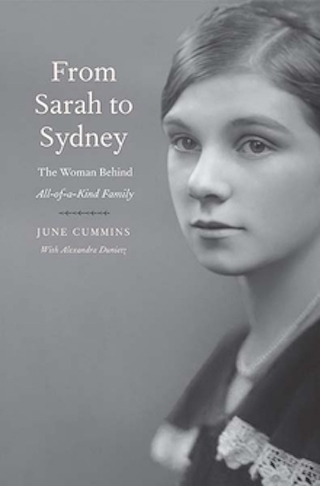

From Sarah to Sydney: The Woman Behind All-of-a-Kind Family by June Cummins with Alix Dunietz. Yale University Press, 400 pages, $35.

Although she has been compared to Louisa May Alcott and Laura Ingalls Wilder, Sydney Taylor, who wrote the much-loved, semi-autobiographical All-of-a-Kind Family series, has not been the subject of a full-length biography until now. The series, known for its heartwarming portrayal of five sisters (and later one brother) in an early 20th-century Jewish immigrant family in New York, was one of the first popular children’s books to feature a Jewish family. The culmination of extensive research by June Cummins, a professor of children’s literature at San Diego State University, From Sarah to Sydney was finished in draft form by Cummins before her untimely death in 2018. Alix Dunietz, a friend and collaborator, prepared the book for publication, according to the acknowledgments by Cummins’s husband, Jonathan Lewis.

Although she has been compared to Louisa May Alcott and Laura Ingalls Wilder, Sydney Taylor, who wrote the much-loved, semi-autobiographical All-of-a-Kind Family series, has not been the subject of a full-length biography until now. The series, known for its heartwarming portrayal of five sisters (and later one brother) in an early 20th-century Jewish immigrant family in New York, was one of the first popular children’s books to feature a Jewish family. The culmination of extensive research by June Cummins, a professor of children’s literature at San Diego State University, From Sarah to Sydney was finished in draft form by Cummins before her untimely death in 2018. Alix Dunietz, a friend and collaborator, prepared the book for publication, according to the acknowledgments by Cummins’s husband, Jonathan Lewis.

The life of Sydney Taylor (born Sarah Brenner) was emblematic in many ways. Growing up in the Lower East Side, the child of German and Eastern European immigrant parents, Taylor’s experiences were typical of many such families. Crowded conditions, poverty, and illness were commonplace. Teachers, librarians, and social workers helped young people to aspire to a better future and to assimilate into what was perceived as “American” culture. The family derived great strength from their devotion to one another, as well as adherence to religious rituals, and values such as obedience, honesty, and kindness.

Cummins considers the first All-of-a-Kind Family book, published in 1951, as groundbreaking and Taylor as “one of the first writers of multicultural literature for children.” Taylor was also, at various times, a socialist, feminist, and challenger of the status quo (Jewish and non-Jewish), although later in life she lamented the loss of tradition and convention. Many of the author’s facts and insights about Sarah — who changed her name to Sydney as a teenager — come from Taylor’s daughter, Jo Marshall, who gave Cummins full access to Taylor’s diaries, letters, scrapbooks, and manuscripts. Since these materials are unpublished, and there are no other in-depth biographies, it’s difficult to cast a critical eye on Cummins’s analysis of Taylor’s life and career. The legion of All-of-a-Kind Family fans will no doubt find the wealth of information interesting, as will librarians, teachers, and children’s literature scholars. Yet the book, perhaps because of its dual authorship, is uneven and often slow-going; one wishes for a smoother, more compelling narrative and more scrutiny of some of Taylor’s contradictions.

The beginning of the book, which provides background on Taylor’s own family, is colorful and thorough. In reality, the Brenners had eight children in all, including three boys, one of whom died in infancy. Included are frank discussions of tensions between Taylor’s mother, Cecilia (Cilly), a German Jew from a prosperous family, and her father, Morris, from a poor family in Eastern Europe; Cilly’s struggles with depression and childbearing; and the family’s financial troubles. Cummins contrasts these issues with the more idyllic version presented to young readers in the All-of-a-Kind Family series.

As a teenager and young adult Taylor embraced left-wing politics and joined the Young People’s Socialist League. She danced with Martha Graham and trained as an actor with Lee Strasberg. Taylor’s contentious (and often puzzling) romantic relationships are examined in perhaps too much detail, including her courtship with her future husband, Ralph Taylor (born Rubin Schneider—schneider being the Yiddish word for tailor). Some of the anecdotes are intriguing but others seem odd and unnecessary, such as the fantasy of one boyfriend about “suckling a woman’s naked breast.”

After the birth of their daughter, Joanne, in 1935, the narrative becomes more muddled, telling Jo’s story into adolescence, then backtracking to describe Taylor’s decades-long involvement in Camp Cejwin, a Jewish summer camp. We get the first hints that Taylor’s progressive viewpoints were beginning to wane when we learn of her disapproval of Jo’s adolescent same-sex relationship. Cummins acknowledges but also increasingly defends Tayler’s shifting values.

Cummins tries to place Taylor’s biography in historical, societal, and psychological context, but often her examination falls short, especially in the later chapters. Perhaps it’s an impossible task. How to reconcile the fictional stories that are so full of empathy and emotion with Taylor’s prickly and irritable personality, and her resistance to the cultural changes of the ’60s and ’70s?

In 1950, Sydney’s life changed dramatically when Ralph submitted the first All-of-a-Kind Family stories in a publishing contest (apparently without Sydney’s knowledge, although this is disputed, as are the reasons why Sydney wrote the book in the first place). The book was an immediate success, and Taylor became a speaker much in demand by librarians, Jewish organizations, and enthusiastic readers. Despite this, Taylor often tangled with her editor, who demanded extensive revisions and consistently tried to make the books less ethnic and more “Americanized.” Not everything Taylor wrote was accepted for publication; her difficulties as a writer reflect the ever-present clash between commercial and artistic goals, as well as the changing world of children’s literature and its market.

In 1950, Sydney’s life changed dramatically when Ralph submitted the first All-of-a-Kind Family stories in a publishing contest (apparently without Sydney’s knowledge, although this is disputed, as are the reasons why Sydney wrote the book in the first place). The book was an immediate success, and Taylor became a speaker much in demand by librarians, Jewish organizations, and enthusiastic readers. Despite this, Taylor often tangled with her editor, who demanded extensive revisions and consistently tried to make the books less ethnic and more “Americanized.” Not everything Taylor wrote was accepted for publication; her difficulties as a writer reflect the ever-present clash between commercial and artistic goals, as well as the changing world of children’s literature and its market.

Growing up, I loved the stories. After all, my grandparents were Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe who settled in New York. I felt a kinship with the All-of-a-Kind-Family, although my family was secular, political, and far less harmonious. There was just enough realism in them to make them feel historical rather than purely nostalgic. Rereading them today, the stories seem both timeless and sentimental, stereotypical but also unique. Some of the language is certainly dated (e.g., “Polack”) and the plots can be contrived, but the cheery, comforting tone remains, as do the affectionate and familiar antics of the sisters, and their noisy, vibrant, old-fashioned world. The books remain in print and continue to sell, a testament to their continuing appeal.

Despite its flaws, From Sarah to Sydney is a welcome, scholarly contribution to the children’s literature field. I hope that future works about Sydney Taylor are more literary and provide additional perspectives on such a remarkable woman and her legacy.

Cyrisse Jaffee is a former children’s and YA librarian, a children’s book editor and book reviewer, and a creator of educational materials for WGBH. She holds a master’s degree in Library Science from Simmons College and lives in Newton, MA.

Thanks so much, Cyrisse, for reviewing this biography! I, too, devoured all of Sydney Taylor’s books when I was a little girl, and I saved them and shared them with my daughters when they were young. It is surprising that despite the enduring popularity of her books, no one had written a full-length biography until now. I look forward to getting my hands on a copy!