Film Review: “A Reckoning in Boston” — Muckraking and Heartbreaking

By Gerald Peary

A Reckoning in Boston demonstrates that fifty years after the bussing-era failures to improve the lives of Black people, there is, in James Rutenbeck’s telling words, “No justice, no truth, no reconciliation.”

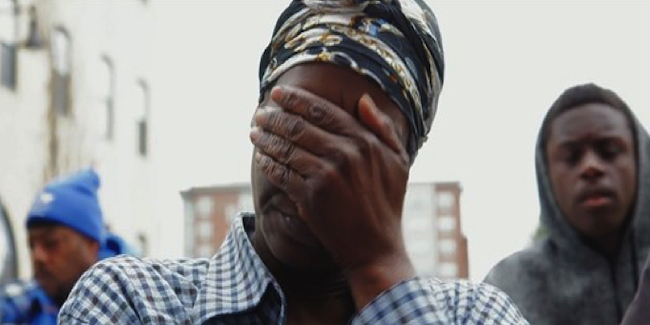

A scene from A Reckoning in Boston.

Probably because it seems so much better here than in Trump’s America, I was seduced by the benign portrait of Boston in Frederick Wiseman’s well-meaning 2020 City Hall. It was Wiseman’s unstated contention that we are fortunate to have a municipal government which responds to the needs of its populace. Thank you, Marty Walsh! But I’ve been awakened, I’ve been set straight, by James Rutenbeck’s new documentary, A Reckoning in Boston. It’s a scathing rebuttal to Wiseman, especially when people of color are in the equation. In equal parts muckraking and heartbreaking, A Reckoning in Boston is the anti-City Hall.

Where the money really flows in the Hub, Rutenbeck attests, is not to “the people” but to the big developers: 18 billion dollars of public funds for the Seaport, with virtually every contract awarded to white companies and corporations. And in the non-white world? A protagonist of A Reckoning in Boston struggles to get the city to donate one meager lot of unused land in a safe neighborhood so that women of color can cultivate it. We are privy to exactly the meetings of the Wiseman film, in which earnest white city employees listen, seemingly sympathetically, to minority petitioners. But what happens afterward to their humble request, their wish for the space to plant a community garden? Rutenbeck couldn’t be more blunt in his voiceover: “The city jerked them around for two years. I came to see it for what it was: a cold and calculated strategy to dash these women’s dreams…a city that is harsh and violent and dismissive of them.”

Playing at the Independent Film Festival of Boston, A Reckoning in Boston lands like dynamite. The director and his cast were on WBUR, there were two favorable articles in the Sunday Globe, and the documentary has been chosen to play on PBS’s prestigious series, Independent Lens. All this recognition is much deserved for the quiet, modest director-editor, Rutenbeck, far more revered in the local film community than known by the general public. He’s long been one of New England’s best documentarians, with a series of excellent, under-the-radar films set in white blue-collar communities. He says, “Most of my films are about people like those I grew up with, in a small farming community in Eastern Iowa.”

His current documentary, perhaps his greatest work, thrust him into a situation which was as perilous as it was uncomfortable: he, from a prosperous white suburb, deciding to shoot at length in multicultured, impoverished Dorchester. In voiceover, Rutenbeck admits his naivete about Black life in the city, including the extraordinary financial challenges facing most residing there. Who can possibly exist on $7, the average total savings for a Boston African-American? “I thought it was a typo when I read it in the Globe,” he confesses. In voiceover, he expresses gratitude to his Dorchester subjects for teaching him so much that he didn’t know, for wanting to “shake me, wake me up.” They share credits on the film as co-producers.

Rutenbeck began his film five years ago by sitting in on the Clemente Course in Dorchester’s Codman Square, a tuition-free night school in humanities “for people living in economic hardship.” His most optimistic scenes are those shot in the classes featuring idealistic, empathetic teachers and adult students of color delighted to be learning, whether it’s the ideas of Aristotle in a philosophy course or the poems of Leroi Jones in a literature class. And what a moving moment in the film when a Clemente class is taken on a field trip to the MFA. “Is it true that Monet paintings look better the farther you stand from them?” notes a perceptive student.

A scene from A Reckoning in Boston.

There’s an adage that casting is everything, and that goes just as much for documentaries as fiction. I applaud Rutenbeck’s choice of two of the students to be his main subjects, and they are riveting and brilliant on camera. But in truth, half-a-dozen participants at the Clemente School would have shined if we got to hear their stories. What an amazing experiment in education! And yet: “I started out looking for transformation [from] the Clemente students,” Rutenbeck says. “I got derailed by the reality of their lives.” He adds these profound words: “Knowledge is power, but so is property, the ability to get a loan or pass wealth to the next generation…not to mention peace, safety.”

Let me acknowledge the superb co-cinematography of Allie Humenuk (my friend) and P.H. O’Brien. And let’s celebrate Rutenbeck’s protagonists, who happily have become his friends over the 5 years of filming. The first is Carl Chandler, a kindly, deep-thinking retiree who, after a divorce, raised his two daughters in a small apartment while himself sleeping in a closet. Most days now he watches dutifully over his small grandchild. In a tender scene, Chandler visits a daughter studying dance in Philadelphia and, with pride and joy, watches her stage performance. He is a self-trained intellectual, a big reader, and the Clemente Course opens up a chance for him, a pipeline to Harvard University.

The second protagonist, Kafi Dixon, likewise has ambitions and aspirations, and they may be even harder to achieve. As a child, she was taken to Thompson Island in the Boston Harbor and discovered, she says, “the healing power of safe spaces.” Her dream was to be a marine biologist. Instead, she’s a Boston bus driver with the 4:30 AM shift, and someone who has been traumatized by living in homeless shelters. She’s the one who has the mission of A Plot of Land of One’s Own, and, as the film shows without a conclusion, Dixon continues to mount the heroic fight to achieve it. And to afford to have equity in her own home, so elusive for people of color.

Tragically, there’s a wait list for affordable housing of 40,000 Bostonians. A Reckoning in Boston demonstrates that fifty years after the bussing-era failures to improve the lives of Black people, there is, in Rutenbeck’s telling words, “No justice, no truth, no reconciliation.”

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema, writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His new feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, is playing at film festivals around the world.

Tagged: A Reckoning in Boston, Boston, City Hall, Independent Film Festival of Boston

[…] A Reckoning in Boston: Kafi Dixon dreams of starting a land cooperative for women of color in Boston who have experienced trauma and disenfranchisement. She drives a city bus by day and studies the humanities in a tuition-free course at night. Her classmate Carl Chandler, a community elder, is the seminar’s intellectual leader. Documenting the students, white suburban filmmaker James Rutenbeck discovers the violence, racism, and gentrification that threaten Kafi and Carl’s well-being in the city. Troubled by his failure to bring the film together, the director enlisted the pair as collaborators, who will be given a share of the documentary’s revenues. Arts Fuse review […]