Book Interview: Translator Brian Nelson on Finally Hearing Émile Zola’s Voice in English

By Bill Marx

“Why read Zola now? Leaving aside sheer enjoyment of his narrative art, I’d say: because his representation of society’s impact on the individuals within it memorably depicts what it means to be a human being in the modern world.”

What first turned me onto the greatness of Émile Zola? In the late ’60s I read British novelist and critic Angus Wilson’s study of the French writer, and his description of the Rougon-Macquart cycle’s iconoclasm was bracing in those heady days of defying a dominating system and its stultifying enablers. Wilson portrayed Zola (1840-1902) as a rebellious spirit, a castigator of the privileged, an implacable opponent of repression, a crusader for truth, a connoisseur of the intractable. My favorite Wilson passage offers a representative jolt:

Then, as now, the average reader wanted a saccharine, a sugar-cake world; it could only be by bludgeoning and violence that he would be persuaded to assist at a black mass in which his sacred bourgeois creeds were recited backwards, his angels of virtue revealed as seven deadly sins, and the very Host of his self-esteem was spat upon. The strength of the greatest Rougon-Macquart novels lay in exactly this kind of assault and battery; an attack, planned with the greatest care and conscientious artistry by a writer whose devotion to the creed of art for art’s sake was by no means lip service, and carried out by a journalist of genius.

This image of Zola as no-holds-barred spitter upon self-esteem, a novelist who in his best work squared the circle of journalism and art for art’s sake, is what initially sent me scurrying to masterpieces such as L’Assommoir, La Terre, and Germinal. And I wasn’t disappointed — they are great, offering many more nuanced rewards than Wilson suggests. But most English translations left me dissatisfied. They came off as wooden, wordy, and starchy. Then I learned that passages from the original texts had been excised so that tender sensibilities would not be offended. And this antiquated approach continued with translations published into the ’50s. When would we feel the full blow of Zola’s bludgeon in English?

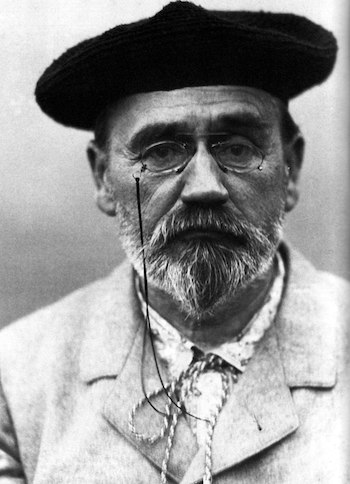

Émile Zola in 1902. Photo: Wiki Commons.

Now, thanks to the Oxford University Press World Classic series, English readers can get their Zola straight and true. Over the past 25 years the publisher has been releasing new, uncut translations (enhanced by translator and critic Brian Nelson’s smart, nonpedantic introductions and notes) of the 20 volumes in the Rougon-Macquart series, which follows the members of a family whose mix of disease and venality was conceived by its author from the onset to reflect breakthroughs in psychology and theories of heredity.

The cycle’s final volume, Doctor Pascal, arrived late last year. (I emailed questions to translator Julie Rose about Zola’s wrap-up.) I have read some of the volumes with enormous pleasure and admiration, and they have complicated my idea of Zola’s brilliance. Yes, he’s a rabble-rouser in the Ibsenite mode, proclaiming the unvarnished truth as he thunders against the hypocritical savagery of a society in transformation. But after reading these nuanced versions I now see Zola as a towering artist/diagnostician of a sick society, a multifarious artificer who, as Nelson argues in his Émile Zola, A Very Short Introduction, was “a narrative artist: a craftsman, a storyteller, a fabulist.” Thanks to Nelson, Rose, and the other superb translators in the OUP series, English readers can finally hear all the registers of Zola’s astonishing voice, from the “sensory immediacy” of his descriptions to his grotesque realism and visionary zeal.

I emailed some questions to Nelson about how the new translations may change our appreciation of Zola’s fiction, the appeal of his novels for filmmakers, and which of his books fit the times we are living through best.

AF: Because of what was deemed their amoral or sensational elements, translations of Zola into English were often bowdlerized. My understanding is that some of the volumes in the OUP series are presenting Zola for the first time (in English) in uncut form. Does this change our understanding of him in any way?

Translator, academic, and critic Brian Nelson.

Brian Nelson: The story of Zola and his translators tells us a lot about how radical, how subversive a writer he was. He took aim at every sacred cow of French society — the Church, the political system, financial institutions, the Army, bourgeois family life. He opened the novel up to a new realm of subjects: working-class life, class relations, gender relations. And his work embodied a new candor and explicitness in the depiction of these subjects (especially in relation to the human body and female sexuality). The shock factor of his novels can be measured not only by the extent to which he was attacked by Establishment critics, but also by the forms of translation-censorship to which he was subject. If, for whatever reason, readers use late 19th-century (or some later) translations, they will gain little sense of the power of Zola’s vision and language. These translations (reprinted in recent times, unfortunately, by publishers wanting to avoid translation costs) were often abridged and replete with excisions and euphemistic lexical choices. Even the series of Zola translations published in the ’50s by Paul Elek are dated and relatively weak.

I think the availability of the whole of Les Rougon-Macquart in the Oxford World’s Classics series represents an enormous advance in the presentation of Zola to the English-speaking world. Not just in terms of completeness but also — at the risk of sounding immodest –in terms of the quality of the new translations, that is, their effective communication of Zola’s voice. Julie Rose’s very fine translation of Le Docteur Pascal, the first new translation since 1957, is a case in point!

AF:Are there any aspects of Zola’s genius that are lost or minimized in even the best of English translations?

Nelson: I think not. All I can do, however, is describe my conception of literary translation and my own practice as a translator. I hold the relatively traditional view that a successful translation lies in convincingly recreating a text as though it were written in the language of the translation, thereby producing in the new reader something as close as possible to the emotional and aesthetic impact of the original on its first readers. It’s about finding the text’s “voice.” The art of translation involves a multiplicity of exact choices about tone, texture, register, rhythm, syntax, echoes, connotations: all those factors that make up “style” and reflect the marriage between style and meaning. With Zola, it’s important to capture the density of his metaphoric language, the color and movement of his descriptions, the powerful rhythms of his narratives.

Each novel carries with it a slightly different set of challenges. My most recent translation for Oxford is of L’Assommoir (to be published later this year as The Assommoir). The key thing with this great novel about slum life in Paris is to be aware of Zola’s astonishing invention of a narrative voice that absorbs into itself the thoughts and feelings of his working-class characters. It’s as if the characters themselves tell their own story. One of the challenges for the translator is to ensure that perspective is aligned with the colloquial style. The translator must make appropriate choices in terms of register and voice. Above all, the translator must avoid translating “up”: rendering in euphemistic or elevated language words and phrases belonging to a robustly colloquial register.

AF: In your excellent Émile Zola, A Very Short Introduction you talk about the writer’s subversiveness. Does Zola remain challenging today? You focus on his strengths as a mythopoetic writer to combat charges that elements in his novels, particularly regarding heredity, have become dated. Why do we need to read Zola now?

Nelson: Zola’s work is in many ways remarkably “undated.” In his 20-volume novel cycle, Les Rougon-Macquart (1871–93), he describes how the various members of the Rougon-Macquart family spread out through all levels of society; and through their lives he examines the social and cultural landscape of the late 19th century, creating an epic sense of social transformation. Zola was fascinated by change, and specifically by the emergence of a new mass society. Why read Zola now? Leaving aside sheer enjoyment of his narrative art, I’d say: because his representation of society’s impact on the individuals within it memorably depicts what it means to be a human being in the modern world. It’s important to note that the world we are living in now is simply a more evolved form of the 19th-century society Zola described. His evocations of the material and social fabric of late 19th-century France — social deprivation and social conflict, the birth of consumer culture, the dynamics of political life, the workings of the stock exchange, the growth of big cities, large-scale real estate speculation, changing gender relations — resonate strongly in our own societies.

A further point is that Zola is an important exemplar of what might be called “committed” writing. He was not committed in the sense that his work was systematically driven by political ideology. But he was committed to the principle of “truth” in art: integrity of representation; and this commitment was based on his conviction that the writer must be socially engaged. He was consciously, and increasingly, a public writer.

AF: You talk about Zola’s journalism in your introduction but not his short stories. Why is that? Douglas Parmée in his introduction in this translation of Zola tales for OUP argues for their distinctive value. He thinks they display a playfulness and light irony that’s missing in Zola’s novels, which some dismiss as elephantine. How playful was Zola?

AF: You talk about Zola’s journalism in your introduction but not his short stories. Why is that? Douglas Parmée in his introduction in this translation of Zola tales for OUP argues for their distinctive value. He thinks they display a playfulness and light irony that’s missing in Zola’s novels, which some dismiss as elephantine. How playful was Zola?

Nelson: There’s far more playfulness and craft in Zola’s novels than people sometimes assume (“elephantine” is an ill-informed stereotype). There’s a lot of humor: the scatological humor of Earth, a burlesque expression of the poetry — and never-ending fertility — of the Earth as Zola wished to evoke it; the satirical comedy of Pot Luck, Zola’s anatomy of bourgeois sexual hypocrisy, with its bedroom farce elements and theatrical use of space; the humor that informs the magnificent group scenes in The Assommoir: the wedding party’s visit to the Louvre, the Rabelaisian-carnivalesque description of Gervaise Macquart’s name day feast.

There’s also another form of play: the play of literary self-consciousness. By bringing out the poetic and visionary aspects of Zola’s novels, critics have done a lot to undermine stereotypes of him as a sensationalist writer fond of squalor and violence, or a stolid producer of novels that relied more on documentation than imagination. Reductive readings of his work have been further undermined by critics (like Henri Mitterand and Susan Harrow) who have noted the surprising ways in which his work prefigures themes and textual strategies of modernist literature. Harrow and Mitterand have shown how Zola’s frequent use of reflexivity (that is, the reflection of the work within the work) links him with 20th-century modernism (the railway line in La Bête humaine, for instance, becomes a metaphor for the narrative system itself).

AF: Zola’s novels have appealed to filmmakers, inspiring a number of first-rate films. In 1928, Money was made into a terrific silent film by Marcel L’Herbier. Would you say Zola — through his use of repeated images and motifs as well as his embrace of the sensational — anticipated cinematic storytelling?

Nelson: This is a rich topic. L’Herbier’s film is remarkable, as are André Antoine’s silent La Terre of 1921, Jean Renoir’s silent Nana of 1926, and his La Bête humaine of 1938. There’s also the silent Russian film, The New Babylon of 1929 (music by Dmitri Shostakovich), which deals with the 1871 Paris Commune, but which has a tangential relationship to Zola’s The Ladies’ Paradise. Zola’s novels have certainly fascinated filmmakers (there have been 80 or so cinematic adaptations of his novels). This is not simply because they are intensely visual, as you suggest, but also (as Leo Braudy has argued) because Zola was obsessed with observation (his novels are full of people observing, spying and eavesdropping), with the nature of observation, and the tension between involvement and detachment; this makes for a strong affinity with the aesthetic and epistemological nature of the cinema. It’s also worth noting, by the way, that in the eight years before his death in 1902, Zola became obsessed with photography, taking thousands of pictures with his 10 cameras and developing them in the basements of his three homes.

AF: You write about Nana and Zola’s conflicted attitudes to women, empathy mixed with misogyny. But what about race and empire? Does the series offer any observations on those topics? You argue that Zola felt himself to be an outsider, which explains his crusade against anti-Semitism in his demand for justice for Dreyfus. How far did that sympathy extend?

Nelson: The themes of race and empire play no significant part in the Rougon-Macquart series. I should note, however, that in his late novel Fécondité (1899), Zola advocated boundless procreation and colonial expansion as solutions to the problem of France’s falling birth rate. But generally speaking, I would stress the enlightened nature of his views. His crusade in defense of Dreyfus (which showed enormous courage) was a crusade against reactionary forms of nationalism and Catholicism; and the whole of Zola’s work after Les Rougon-Macquart, during the last 10 years of his life, can be seen as having been written in anticipation of and under the impulse of the profound social crisis embodied in the Dreyfus Affair. Essentially, Zola’s later works (Three Cities and The Four Gospels) set out a utopian vision of a new, revitalized, republican France; they extol the power of science, technology, education, and egalitarianism as means of overcoming religious constraint and social exploitation. It’s a vision that is (apart from Zola’s traditionalist view of the role of women) progressive and “modern.”

AF: Has the OUP complete Rougon-Macquart series stimulated interest in Zola beyond the academy? And do you have a Zola novel that you believe should receive more attention than it has? (Given the state of “global” finance — and the growing extremes between rich and poor — Money seems to me to be worth reconsideration.)

Nelson: Zola became, and remained, a best-selling author with the publication of L’Assommoir in 1877. His reputation in the UK and the US began to improve from the 1950s onwards, with pioneering critical appraisals by Angus Wilson and F.W.J. Hemmings. I think the “complete” Rougon-Macquart produced by Oxford has given a great boost to the general public’s appreciation of Zola. Sales have been strong (my own translation of The Ladies’ Paradise, published in 1995, has sold 100,000 copies — thanks significantly, I might add, to the BBC’s TV version of 2012, The Paradise). That TV miniseries is itself a major sign of interest in Zola. So was the 2015 BBC Radio 4 program, broadcast over many weeks, Blood, Sex and Money: The Life and Work of Émile Zola, featuring Glenda Jackson as Aunt Dide, the matriarch of the Rougon-Macquart family. And very recently there was a long essay on Zola, based on three of the OUP translations, in the New York Review of Books (Aaron Matz, “Inheriting Hunger”, NYRB, Feb. 11, 2021, pp. 36–38).

Nelson: Zola became, and remained, a best-selling author with the publication of L’Assommoir in 1877. His reputation in the UK and the US began to improve from the 1950s onwards, with pioneering critical appraisals by Angus Wilson and F.W.J. Hemmings. I think the “complete” Rougon-Macquart produced by Oxford has given a great boost to the general public’s appreciation of Zola. Sales have been strong (my own translation of The Ladies’ Paradise, published in 1995, has sold 100,000 copies — thanks significantly, I might add, to the BBC’s TV version of 2012, The Paradise). That TV miniseries is itself a major sign of interest in Zola. So was the 2015 BBC Radio 4 program, broadcast over many weeks, Blood, Sex and Money: The Life and Work of Émile Zola, featuring Glenda Jackson as Aunt Dide, the matriarch of the Rougon-Macquart family. And very recently there was a long essay on Zola, based on three of the OUP translations, in the New York Review of Books (Aaron Matz, “Inheriting Hunger”, NYRB, Feb. 11, 2021, pp. 36–38).

As for your second question, I’d like to speak up for Earth (which Julie Rose and I translated together). This novel, focused on French peasant life, has always been recognized as one of Zola’s finest achievements, but it seems to have fallen out of favor in recent years (though when Zola embarked on it, he said he felt it would be his favorite among his novels). Earth has an extraordinary epic sweep, and the pungency of Zola’s language is exceptional even within an œuvre celebrated for its robustness. Earth is stylistically interesting in that Zola proceeds by stringing clauses together, with scant use of conjunctions. The effect is to produce a relentless virile energy, sometimes bordering on breathlessness, sometimes amplified into boisterous hilarity, always sweeping the narrative along at breakneck speed. It’s a great novel.

In terms of topicality, yes, Money portrays a financial crisis (inspired by the collapse of a French finance house, the Union Générale) that is uncannily like those of recent times. Similarly, His Excellency Eugène Rougon, which describes the court and political circles during Napoleon III’s Second Empire, is surprisingly modern in its representation of the dynamics of the political: the scheming and the rivalries, the patronage and the string-pulling, and the manipulation of language for political purposes (“fake news” has a long pre-history!).

Brian Nelson is a professor emeritus in French Studies at Monash University, Melbourne. He is best known for his translations and critical studies of the novels of Émile Zola. In addition to Émile Zola: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford, 2020), they include The Cambridge Companion to Zola (2007), Naturalism in the European Novel (1992), and Zola and the Bourgeoisie (1983), and translations, for Oxford World’s Classics, of L’Assommoir, The Belly of Paris, Earth (with Julie Rose), The Fortune of the Rougons, His Excellency Eugène Rougon, The Kill, The Ladies’ Paradise, and Pot Luck. He won the 2015 New South Wales Premier’s Prize for Translation. Other publications include The Cambridge Introduction to French Literature (Cambridge, 2015). Since 2020 he has been engaged, as co-editor and contributing translator, on a new edition of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time for Oxford World’s Classics.

Tagged: 19th century French literature, Brian Nelson, Oxford University Press, translation

[…] Pascal marked the first time that the 20-book cycle was available in print under one publisher. I spoke to Nelson, who contributed thoughtful introductions and notes to all the volumes, about the ways these new […]