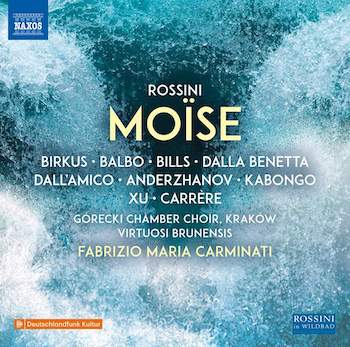

Opera Album Review: Rossini’s Splendid Passover Opera for Paris — “Moïse et Pharaon”

By Ralph P. Locke

Just in time for Passover: another fine world-premiere Rossini recording, the 1827 French version of his Moses-in-Egypt opera.

Gioachino Rossini: Moïse et Pharaon, ou le passage de la Mer rouge

Silvia Dalla Benetta (Sinaïde), Elisa Balbo (Anaï), Randall Bills (Aménophis), Alexei Birkus (Moïse), Luca Dall’Amico (Pharaon).

Gorecki Chamber Choir, Virtuosi Brunensis, cond. Fabrizio Maria Carminati

Naxos 8.660473-75 [3 CDs] 168 minutes

Click here to purchase or listen to the beginning of each track.

Here, just in time for Passover 2021, is the world-premiere recording of Rossini’s 1827 opera Moïse et Pharaon, ou le Passage de la Mer rouge.

Here, just in time for Passover 2021, is the world-premiere recording of Rossini’s 1827 opera Moïse et Pharaon, ou le Passage de la Mer rouge.

You may recognize at least one tune in it. And this reminds me of a “principle” that I’ve developed over the years: if an opera has given at least one beloved melody to the musical world, the rest of the work is probably well worth getting to know.

This is certainly the case with Rossini’s opera about Moses freeing the Israelites from Egyptian bondage. The tune in question occurs in a big ensemble prayer as the Israelites stand by the Red Sea, just steps ahead of the Egyptian chariots. You may know it from Paganini’s oft-recorded “Moses Fantasy” for violin unaccompanied. The whole opera turns out to be fascinating indeed, with many tunes on the level of that one, or even somewhat finer!

168 minutes is a lot of Rossini for some people, barely enough for others. Here we have what must be one of the longest of Rossini’s operas, because it is one of his serious ones, further expanded for performance at the Paris Opéra.

In recent decades, the original version of the work — composed in Italian and forgotten for a century or more — has become relatively familiar again on recordings, under the title Mosè in Egitto (Moses in Egypt; 1818). There have been at least six CD or DVD recordings (plus several pirated CDs, e.g., one with Boris Christoff in the title role). I particularly recommend a shapely, well-recorded CD release under Claudio Scimone, featuring June Anderson and Ruggiero Raimondi, made when they were in splendid early-career voice.

Now Naxos (which has already made available two performances of the 1818 version, one on CD, the other on DVD) brings us the 1827 French work, whose full title translates as “Moses and Pharaoh, or the Crossing of the Red Sea.” Naxos, following certain of the primary sources for the work, calls it simply Moïse.

The excellent booklet essays by Annelies Andries and Reto Müller explain how, for the 1827 version, Rossini and his French librettists rearranged the order of the 1818 opera’s scenes, reworked much of the music, and added many new sections, such as an extensive ballet. (The Opéra insisted that any full-length opera include a ballet. Decades later, this requirement would lead Wagner to create the colorful Venusberg music for the Paris version of Tannhäuser.)

The result is apparently the first complete CD recording of the 1827 French version, and I recommend it heartily to anybody interested in the early history of French Grand Opera. Here Rossini experimented — as he would again, two years later, in Guillaume Tell — with finding ways to tell a story from the legendary past in a grand, inspiring way. He thereby set a path that Meyerbeer, Halévy, Donizetti, Verdi, Gounod, Saint-Saëns, and others would follow.

Not least, he varied his orchestral colors greatly, offering solemn passages for brass choir or a touching flute solo. The latter opens the Act 2 aria in which the pharaoh’s wife pleads with her son to give up his love for the Hebrew maiden Anaï. (It’s complicated because the plot elaborates wildly on the Bible story. The mother herself has secretly accepted Jehovah as Lord. Miriam is called Marie, perhaps as a way of encouraging, or at least allowing, a Christian interpretation.)

A scene from the production of Moïse und Pharaon in Bad Wildbad, in July 2018. Photo: Patrick Pfeiffer.

Particularly striking are the many descriptive passages, such as when the skies brighten again after the plague of darkness is lifted. (Rossini was surely thinking of the “Let there be light” in Haydn’s The Creation.) Or, toward the end, the turbulent closing of the Red Sea upon Pharaoh’s troops.

And then there are the reliable pleasures of any Rossini opera, namely lilting melody, often blossoming into exquisite or passionate coloratura (depending on the situation). This becomes all the more impressive, or tingle-inducing, in sections that involve multiple cast members. One of my favorite such passages is in the third-act finale: after Moses makes the statue of Isis collapse and the Ark of the Covenant then appears in the sky (as I said, a lot of the plot is not in the Bible!), everyone expresses a kind of frozen astonishment for three glorious minutes, to an accompaniment that features harp arpeggios (“Je tremble et soupire”—”I tremble and sigh”).

If you don’t know the Mosè/Moïse complex, you might be better off with a recording of the 1818 Italian version (such as the Scimone). The present recording comes from three staged performances in summer 2018 at the renowned “Rossini in Wildbad” festival (in Germany’s Black Forest region), and it bears some of the near-inevitable shortcomings when a complex work is recorded that way. The orchestra, not very large, sounds even smaller because it is recorded without much resonance. (Perhaps the mikes were pointed mainly at the stage and away from the orchestra, in order to avoid catching rustling and coughing from the audience.) Also, in the opening scenes, the chorus and soloists alike often sing slightly below pitch compared to the orchestra. Were they standing far from the pit, making it hard for them to hear? By contrast, this same choral group is perfectly in tune with the orchestra — which helps one appreciate how gorgeously they sing! — at the beginning of Act 2 when, at Moses’s behest, God has afflicted Egypt with a plague of darkness.

Alexei Birkus (from Russia), as Moïse, is often slightly flat even when he is standing front and center, near the orchestra. This a problem that might have been fixed if the work had been recorded in studio sessions, which allow multiple takes at different times of the day. (A given singer might find late morning, say, more congenial than late afternoon.) Also, though Birkus has a sonorous voice that conveys Mosaic authority, his coloratura is not always clean.

A scene from the production of Moïse und Pharaon in Bad Wildbad in July, 2018. Photo: Patrick Pfeiffer.

Still, the work comes across well, thanks to the otherwise fine cast, led by two remarkable sopranos: Silvia Dalla Benetta (whom I have previously admired in three operas by Rossini, including Zelmira and Eduardo e Cristina, and one by Bellini) and Elisa Balbo (who sings here as beautifully as in Rossini’s Maometto II, and indeed with steadier tone than in Lo schiavo, an important opera by the skillful Brazilian-born Carlos Gomes).

Tenor Randall Bills is eloquent and convincingly heroic at the top end of his range though he is sometimes thin at the bottom. Patrick Kabongo, from the Republic of the Congo, is exquisite in the smaller role of Eliézer. The rest of the cast produces healthy, stylish singing: Luca Dall’Amico (as Pharaoh) is more precise than Birkus (Moses) but produces a less resonant sound.

Carminati, a conductor I have not previously encountered, keeps up the pace nicely, and the orchestra (from Moravia, in the Czech Republic) and chorus (from Poland) follow him to the hilt.

A 2003 La Scala DVD of the Paris version, though perhaps not as complete as the new CD, features singers who were, or would soon become, major stars (Frittoli, Ganassi, Muraro, Schrott, Abdrazakov), conducted by Riccardo Muti. The bits I watched on YouTube were captivating. Ditto for a YouTube version featuring Cecilia Gasdia, Shirley Verrett, and Samuel Ramey (under Georges Prêtre), with blurry video but clear sound. But the new CD recording gives you every note that Rossini wrote, in a shapely and largely convincing performance. French-only libretto at the Naxos website, with helpful track numbers in red.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). A version of this review first appeared in American Record Guide and here appears by kind permission.