Author Interview: Kevin Mattson on a Genuine Culture War — Punks versus Reagan

By Blake Maddux

The real culture war in 1980s America was waged by young people who were trying to create their own culture and jealously rejected corporate culture along the way.

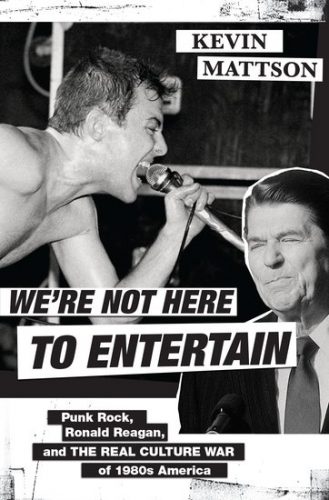

We’re Not Here to Entertain: Punk Rock, Ronald Reagan, and the Real Culture War of 1980s America by Kevin Mattson. Oxford University Press, 387 pages, $27.95.

Buy at Bookshop

In the early 1980s, Kevin Mattson was a suburban teenager who was active in Washington, D.C.’s burgeoning punk rock movement. About a decade later, his mentor at the University of Rochester — the influential historian and social critic Christopher Lasch, who died the year that Mattson would receive his doctorate — politely advised him against writing his dissertation on the social, intellectual, and political importance of the many such scenes that proliferated from coast to coast.

Last August, with the benefit of temporal distance, perspective, and new archives at several major universities, Mattson published a book on that very topic.

Because it focuses on a major American political figure, We’re Not Here to Entertain follows in the footsteps of Mattson’s two most recent books. However, while the covers of those volumes feature the chosen politician (Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter), this one presents us with an exasperated Ronald Reagan over whom is angrily hovering Jello Biafra, the leader of the San Francisco punk rockers Dead Kennedys. Unlike the ivy tower highbrows who dominated Mattson’s other studies in intellectual history, the men (and it is mostly men) of ideas in We’re Not Here to Entertain are Biafra and the members of fellow punk bands such as Minutemen, Minor Threat, Black Flag, and Circle Jerks. These largely autodidactical (if that’s not a word, then I’ll take credit for it) individuals were the combatants in a cultural war waged against what they saw as the belligerent and uncaring policies of The Gipper.

Mattson, who started teaching at Ohio University immediately after I was no longer a graduate student there in 2001, spoke to me about the book in a recent phone interview.

The Arts Fuse: The subject matter of We’re Not Here to Entertain is different from your other studies, but it shares a lot of the same thematic interests.

Kevin Mattson: I call the book a work of intellectual history. I make the argument throughout that, for the generation I focus on — and that includes me — punk was one of the things that led to intellectual engagement. There are stories about Jello Biafra of the Dead Kennedys lecturing on stage. He said things like, “Go out and read a book. Inform yourself on what’s going on in American politics and ideas!” I remember being at a number of those shows, and this is really what got me interested in intellectual history, even though I didn’t go immediately from the punk scene to studying intellectual history.

AF: Why did you decide that this topic was worthy of the time and effort required for a book-length treatment?

KM: When I was engaged in the movement in Washington, D.C., from about 1981-1985 or so, there were amazing misrepresentations of what punk was about in the mainstream media. The television show CHiPS did an episode with a loud, aggressive punk band at its center. Quincy, the show about a medical examiner, did an episode where basically the allegation was that punk rock encouraged kids to kill one another. (This story includes clips from both episodes. This link includes another clip from CHiPS and the entire episode of Quincy, M.E. And don’t blame me if you choose to watch Erik Estrada sing “Celebration.”)

These charges were kind of outlandish and they were among my first intellectual wakeups. As I was thinking about writing We’re Not Here to Entertain, I wanted to cast a true light on what punk was about, or at least what some elements of punk were about. When we look back on it now we still don’t understand some of the more important elements that made it a movement.

The other thing that I should point out is that I was fortunate that a number of new archives were being created across the country, including at Cornell and the University of California, Berkeley. A lot of people connected with punk were putting together their ephemera into archives.

Historian Kevin Mattson — the real culture war in ’80s America was the fact that some young people were trying to create their own culture and were rejecting corporate culture along the way.

AF: The subtitle mentions “the real culture war” of the ’80s. What notion of a a ‘culture war’ are you aiming to counteract?

KM: When we think of the period’s culture wars we usually think about debates about issues such as political correctness in academia or abortion. Things that polarized people. For me, the real culture war that was going on back in ’80s America was that some young people were trying to create their own culture and rejected corporate culture along the way. They also rejected Ronald Reagan, who in their minds was a flack for the corporate entertainment industry. Because he was so heavily influenced by the popular entertainment industry it was no surprise to these rebels that he celebrated people like Michael Jackson and other popular artists. So, for me, the culture war was really about kids forming their own counterculture in opposition to the corporate culture that they were being spoonfed.

That was the culture war that really mattered back then, not all the skirmishes about the closing of the American mind, criticism of political correctness, abortion, or the concerns over the public funding of artists who some found obscene.

AF: In what manner did ’80s punks both reject and embrace hippie values?

KM: There’s a total anti-hippie attitude among a bunch of punks. You can see that especially in Raymond Pettibon’s artwork. He usually depicted Charles Manson and hippies as zoned-out figures who were not engaged in anything beyond their own search for drugs or what-have-you. A lot of that animus is obviously generational. Most of the people involved in the punk scene during the ’80s were people we would classify a Generation X. The hippie movement would have been associated with Baby Boomers. You see that conflict especially in movies like The Big Chill, where there’s a celebration of the great heyday of ’60s hippie culture.

But as I was doing my research on punk I discovered that there was actually considerable appreciation of the kind of ’60s activism connected to the hippie counterculture. For instance, one person at MAXIMUMROCKNROLL goes back to the People’s Park struggle in Berkeley, CA, and says, this is something we can make sense of for ourselves because we’re doing the things that they were doing, which is occupying public space and trying to turn it over into community control. As I did more research, this generational interaction became more complex than a simple rejection of hippies.

AF: What do you hope that newcomers to the subject as well as old fans will learn from We’re Not Here to Entertain?

KM: How much more widely spread punk culture was throughout the United States; it was present in places you wouldn’t expect it to be. I didn’t really know until I went into the archives just how extensive the movement really was. I pulled up zines from places in Florida and Oklahoma, places you just wouldn’t expect to see a counterculture. Ohio had a bunch of zines.

Punk wasn’t just music. You can find traces of it in artwork and in cyberpunk, which is on the rise during the period of time that the book covers. [There were the challenges of] finding venues to use for shows as well as creating venues that were different from the traditional nightclub. Playing in shopping malls in certain cases! And the fact that punk inspired a number of people to understand their world politically. The culture was imbued with political activism, particularly the engagement that came out of the San Francisco punk scene, which was probably the most highly politicized punk scene across the states.

There are also characters here that probably would not be included in other books about the period. The participant that many may be surprised to see is Matt Groening. His writing for the Los Angeles Reader and LA Weekly while this punk movement was going on was really crucial to promoting it. And he was a huge fan of Minutemen.

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who regularly contributes to the Arts Fuse, the Somerville Times, and the Beverly Citizen. He has also written for DigBoston, the ARTery, Lynn Happens, the Providence Journal, The Onion’s A.V. Club, and the Columbus Dispatch. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife and one-year-old twins–Elliot Samuel and Xander Jackson–in Salem, Massachusetts.

Is there any similar book about new wave movement on this topic ?

Hi Georgiano. Thank you for reading and for your question. Rip It Up and Start Again by Simon Reynolds (a Brit) might be worth checking out. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/291130/rip-it-up-and-start-again-by-simon-reynolds/

Best,

Blake